Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▲ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

13 Jul 2023

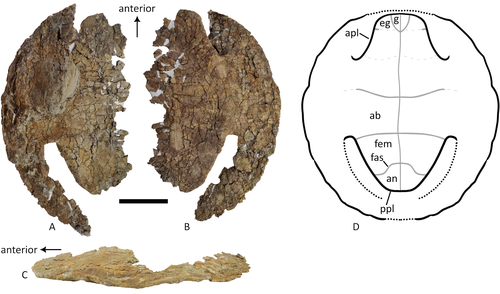

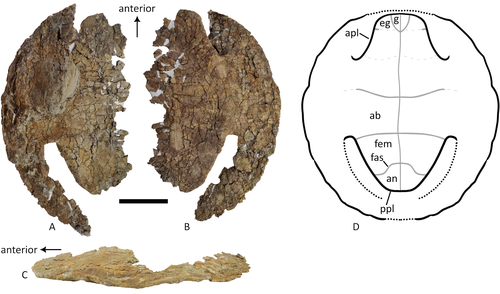

A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USAKa Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3acNew baenid turtle material from the Campanian of WyomingRecommended by Jérémy Anquetin based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian

The Baenidae form a diverse extinct clade of exclusively North American paracryptodiran turtles known from the Early Cretaceous to the Eocene (Hay, 1908; Gaffney, 1972; Joyce and Lyson, 2015). Their fossil record was recently extended down to the Berriasian-Valanginian (Joyce et al. 2020), but the group probably originates in the Late Jurassic because it is usually retrieved as the sister group of Pleurosternidae in phylogenetic analyses. However, baenids only became abundant during the Late Cretaceous, when they are restricted in distribution to the western United States, Alberta and Saskatchewan (Joyce and Lyson, 2015). During the Campanian, baenids are abundant in the northern (Alberta, Montana) and southern (Texas, New Mexico, Utah) parts of their range, but in the middle part of this range they are mostly represented by poorly diagnosable shell fragments. In their new contribution, Wu et al. (2023) describe a new articulated baenid specimen from the Campanian Mesaverde Formation of Wyoming. Despite its poor preservation, they are able to confidently assign this partial shell to Neurankylus sp., hence definitively confirming the presence of baenids and Neurankylus in this formation. Incidentally, this new specimen was found in a non-fluvial depositional environment, which would also confirm the interpretation of Neurankylus as a pond turtle (Hutchinson and Archibald, 1986; Sullivan et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2023; see also comments from the second reviewer). The study of Wu et al. (2023) also includes a detailed account of the state of the fossil when it was discovered and the subsequent extraction and preparation procedures followed by the team. This may seem excessive or out of place to some, but I agree with the authors that such information, when available, should be more commonly integrated into scientific articles describing new fossil specimens. Preparation and restoration can have a significant impact on the perceived morphology. This must be taken into account when working with fossil specimens. The chemicals or products used to treat, prepare, or consolidate the specimens are also important information for long-term curation. Therefore, it is important that such information is recorded and made available for researchers, curators, and preparators. References Gaffney, E. S. (1972). The systematics of the North American family Baenidae (Reptilia, Cryptodira). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 147(5), 241–320. Hay, O. P. (1908). The Fossil Turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.12500 Hutchison, J. H., and Archibald, J. D. (1986). Diversity of turtles across the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary in Northeastern Montana. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(86)90133-1 Joyce, W. G., and Lyson, T. R. (2015). A review of the fossil record of turtles of the clade Baenidae. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 56(2), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.3374/014.058.0105 Joyce, W. G., Rollot, Y., and Cifelli, R. L. (2020). A new species of baenid turtle from the Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation of South Dakota. Fossil Record, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5194/fr-23-1-2020 Sullivan, R. M., Lucas, S. G., Hunt, A. P., and Fritts, T. H. (1988). Color pattern on the selmacryptodiran turtle Neurankylus from the Early Paleocene (Puercan) of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Contributions in Science, 401, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.241286 Wu, K. Y., Heuck, J., Varriale, F. J., and Farke, A. (2023). A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA. PaleorXiv, uk3ac, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3ac | A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA | Ka Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke | <p>The Mesaverde Formation of the Wind River and Bighorn basins of Wyoming preserves a rich yet relatively unstudied terrestrial and marine faunal assemblage dating to the Campanian. To date, turtles within the formation have been represented prim... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiogeography, Vertebrate paleontology | Jérémy Anquetin | 2023-01-16 16:26:43 | View | |

25 Oct 2022

Morphometric changes in two Late Cretaceous calcareous nannofossil lineages support diversification fueled by long-term climate changeMohammad Javad Razmjooei, Nicolas Thibault https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/nfyc9Insights into mechanisms of coccolithophore speciation: How useful is cell size in delineating species?Recommended by Emilia Jarochowska based on reviews by Andrej Spiridonov and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrej Spiridonov and 1 anonymous reviewer

Calcareous plankton gives us perhaps the most complete record of microevolutionary changes in the fossil record (e.g. Tong et al., 2018; Weinkauf et al., 2019), but this opportunity is not exploited enough, as it requires meticulous work in documenting assemblage-level variation through time. Especially in organisms such as coccolithophores, understanding the meaning of secular trends in morphology warrants an understanding of the functional biology and ecology of these organisms. Razmjooei and Thibault (2022) achieve this in their painstaking analysis of two coccolithophore lineages, Cribrosphaerella ehrenbergii and Microrhabdulus, in the Late Cretaceous of Iran. They propose two episodes of morphological change. The first one, starting around 76 Ma in the late Campanian, is marked by a sudden shift towards larger sizes of C. ehrenbergii and the appearance of a new species M. zagrosensis from M. undulatus. The second episode around 69 Ma (Maastrichtian) is inferred from a gradual size increase and morphological changes leading to probably anagenetic speciation of M. sinuosus n.sp. The study remarkably analyzed the entire distributions of coccolith length and rod width, rather than focusing on summary statistics (De Baets et al., in press). This is important, because the range of variation determines the taxon’s evolvability with respect to the considered trait (Love et al., 2022). As the authors discuss, cell size in photosymbiotic unicellular organisms is not subject to the same constraints that will be familiar to researchers working e.g. on mammals (Niklas, 1994; Payne et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2016). Furthermore, temporal changes in size alone cannot be interpreted as evolutionary without knowledge of phenotypic plasticity and environmental clines present in the basin (Aloisi, 2015). The more important is that this study cross-tests size changes with other morphological parameters to examine whether their covariation supports inferred speciation events. The article addresses as well the effects of varying sedimentation rates (Hohmann, 2021) by, somewhat implicitly, correcting for the stratophenetic trend using an age-depth model and accounting for a hiatus. Such multifaceted approach as applied in this work is fundamental to unlock the dynamics of speciation offered by the microfossil record. The study highlights also the link between shifts in size and diversity. Klug et al. (2015) have previously demonstrated that these two variables are related, as higher diversity is more likely to lead to extreme values of morphological traits, but this study suggests that the relationship is more intertwined: environmentally-driven rise in morphological variability (and thus in size) can lead to diversification. It is a fantastic illustration of the complexity of morphological evolution that, if it can be evaluated in terms of mechanisms, provides an insight into the dynamics of speciation.

References Aloisi, G. (2015). Covariation of metabolic rates and cell size in coccolithophores. Biogeosciences, 12(15), 4665–4692. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-4665-2015 De Baets, K., Jarochowska, E., Buchwald, S. Z., Klug, C., and Korn, D. (In Press). Lithology controls ammonoid size distribution. Palaios. Hohmann, N. (2021). Incorporating information on varying sedimentation rates into palaeontological analyses. PALAIOS, 36(2), 53–67. doi: 10.2110/palo.2020.038 Klug, C., De Baets, K., Kröger, B., Bell, M. A., Korn, D., and Payne, J. L. (2015). Normal giants? Temporal and latitudinal shifts of Palaeozoic marine invertebrate gigantism and global change. Lethaia, 48(2), 267–288. doi: 10.1111/let.12104 Love, A. C., Grabowski, M., Houle, D., Liow, L. H., Porto, A., Tsuboi, M., Voje, K.L., and Hunt, G. (2022). Evolvability in the fossil record. Paleobiology, 48(2), 186–209. doi: 10.1017/pab.2021.36 Niklas, K. J. (1994). Plant allometry: The scaling of form and process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Payne, J. L., Boyer, A. G., Brown, J. H., Finnegan, S., Kowalewski, M., Krause, R. A., Lyons, S.K., McClain, C.R., McShea, D.W., Novack-Gottshall, P.M., Smith, F.A., Stempien, J.A., and Wang, S. C. (2009). Two-phase increase in the maximum size of life over 3.5 billion years reflects biological innovation and environmental opportunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(1), 24–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806314106 Razmjooei, M. J., and Thibault, N. (2022). Morphometric changes in two Late Cretaceous calcareous nannofossil lineages support diversification fueled by long-term climate change. PaleorXiv, nfyc9, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/nfyc9 Smith, F. A., Payne, J. L., Heim, N. A., Balk, M. A., Finnegan, S., Kowalewski, M., Lyons, S.K., McClain, C.R., McShea, D.W., Novack-Gottshall, P.M., Anich, P.S., and Wang, S. C. (2016). Body size evolution across the Geozoic. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 44(1), 523–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012147 Tong, S., Gao, K., and Hutchins, D. A. (2018). Adaptive evolution in the coccolithophore Gephyrocapsa oceanica following 1,000 generations of selection under elevated CO2. Global Change Biology, 24(7), 3055–3064. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14065 Weinkauf, M. F. G., Bonitz, F. G. W., Martini, R., and Kučera, M. (2019). An extinction event in planktonic Foraminifera preceded by stabilizing selection. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0223490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223490 | Morphometric changes in two Late Cretaceous calcareous nannofossil lineages support diversification fueled by long-term climate change | Mohammad Javad Razmjooei, Nicolas Thibault | <p>Morphometric changes have been investigated in the two groups of calcareous nannofossils, <em>Cribrosphaerella ehrenbergii</em> and <em>Microrhabdulus undosus</em> across the Campanian to Maastrichtian of the Zagros Basin of Iran. Results revea... |  | Biostratigraphy, Evolutionary theory, Fossil record, Microfossils, Micropaleontology, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Nanofossils, Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoceanography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology, Paleoenvironments, Taxonomy | Emilia Jarochowska | 2020-08-29 12:23:51 | View | |

27 May 2020

The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK)Jérémy Anquetin, Charlotte André https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/7pa5cA recommendation of: The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK)Recommended by Hans-Dieter Sues based on reviews by Igor Danilov and Serjoscha EversStem- and crown-group turtles have a rich and varied fossil record dating back to the Triassic Period. By far the most common remains of these peculiar reptiles are their bony shells and fragments of shells. Furthermore, if historical specimens preserved skulls the preparation techniques at that time were inadequate for elucidating details of the cranial structure. Thus, it comes as no surprise that most of the early research on turtles focused on the structure of the shell with little attention paid to other parts of the skeleton. Starting in the 1960s, this changed as researchers realized that there is considerable variation in the structure of turtle shells even within species and that new methods of fossil preparation, especially chemical methods, could reveal a wealth of phylogenetically important features in the structure of the skulls of turtles. The principal worker was Eugene S. Gaffney of the American Museum of Natural History (New York) who in a series of exquisitely illustrated monographs revolutionized our understanding of turtle osteology and phylogeny. Over the last decade or so, a new generation of researchers has further refined the phylogenetic framework for turtles and continued the work by Gaffney. One of the specialists from this new generation is Jérémy Anquetin who, with a number of colleagues, has revised many of the Jurassic-age stem-turtles that existed in coastal marine settings in what is now Europe. Collections in France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK house numerous specimens of these forms, which attracted the interest of researchers as early as the first decades of the nineteenth century. Despite this long history, however, the diversity and interrelationships of these marine taxa remained poorly understood. In the present study, Anquetin and his colleague Charlotte André extend the fossil record of these stem-turtles, recently hypothesized as a clade Thalassochelydia, into the Early Cretaceous (Anquetin & André 2020). They present an excellent anatomical account on a well-preserved cranium from the Purbeck Formation of Dorset (England) that can be referred to Thalassochelydia and augments our knowledge of the cranial morphology of this clade. Anquetin & André (2020) make a good case that this specimen belongs to the same taxon as shell material long ago described as Hylaeochelys belli. References Anquetin, J., & André, C. (2020). The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK). PaleorXiv, 7pa5c, version 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/7pa5c | The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK) | Jérémy Anquetin, Charlotte André | <p>**Background.** The mostly Berriasian (Early Cretaceous) Purbeck Group of southern England has produced a rich turtle fauna dominated by the freshwater paracryptodires *Pleurosternon bullockii* and *Dorsetochelys typocardium*. Each of these spe... |  | Comparative anatomy, Paleoecology, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Hans-Dieter Sues | 2020-01-30 10:37:07 | View | |

15 Dec 2022

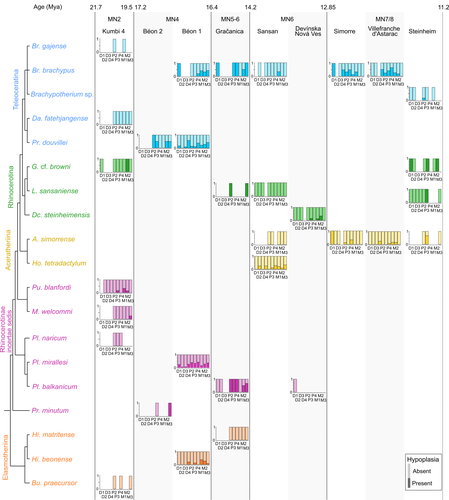

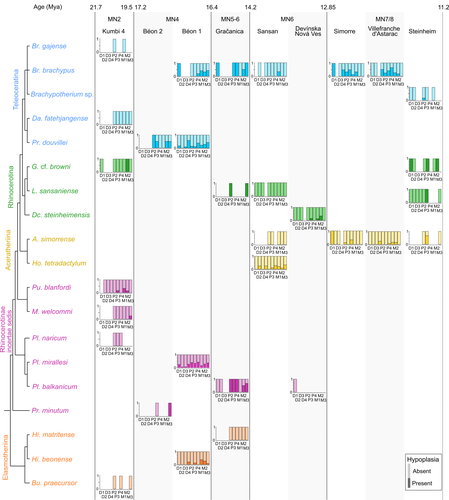

Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: impact of climate changesManon Hullot, Gildas Merceron, Pierre-Olivier Antoine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.06.490903New insights into the palaeoecology of Miocene Eurasian rhinocerotids based on tooth analysisRecommended by Alexandra Houssaye based on reviews by Antigone Uzunidis, Christophe Mallet and Matthew MihlbachlerRhinocerotoidea originated in the Lower Eocene and diversified well during the Cenozoic in Eurasia, North America and Africa. This taxon encompasses a great diversity of ecologies and body proportions and masses. Within this group, the family Rhinocerotidae, which is the only one with extant representatives, appeared in the Late Eocene (Prothero & Schoch, 1989). They were well diversified during the Early and Middle Miocene, whereas they began to decline in both diversity and geographical range after the Miocene, throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, in conjunction with the marked climatic changes (Cerdeño, 1998). In Eurasian Early and Middle Miocene fossil localities, a variety of species are often associated. Therefore, it may be quite difficult to estimate how these large herbivores cohabited and whether competition for food resources is reflected in a diversity of ecological niches. The ecologies of these large mammals are rather poorly known and the detailed study of their teeth could bring new elements of answer. Indeed, if teeth carry a strong phylogenetic signal in mammals, they are also of great interest for ecological studies, and they have the additional advantage of being often numerous in the fossil record. Hullot et al. (2022) analysed both dental microwear texture, as an indicator of dietary preferences, and enamel hypoplasia, to identify stress sensitivity, in a large number of rhinocerotid fossil teeth from nine Neogene (Early to Middle Miocene) localities in Europe and Pakistan. Their aim was to analyse whether fossil species diversity is associated with a diversity of ecologies, and to investigate possible ecological differences between regions and time periods in relation to climate change. Their results show clear differences in time and space between and within species, and suggest that more flexible species are less vulnerable to environmental stressors. Very few studies focus on the palaeocology of Miocene rhinos. This study is therefore a great contribution to the understanding of the evolution of this group.

References Cerdeño, E. (1998). Diversity and evolutionary trends of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 141, 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00003-0 Hullot, M., Merceron, G., and Antoine, P.-O. (2022). Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: Impact of climate changes. BioRxiv, 490903, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.06.490903 Prothero, D. R., and Schoch, R. M. (1989). The evolution of perissodactyls. New York: Oxford University Press. | Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: impact of climate changes | Manon Hullot, Gildas Merceron, Pierre-Olivier Antoine | <p>Major climatic and ecological changes are documented in terrestrial ecosystems during the Miocene epoch. The Rhinocerotidae are a very interesting clade to investigate the impact of these changes on ecology, as they are abundant and diverse in ... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Paleopathology, Vertebrate paleontology | Alexandra Houssaye | 2022-05-09 09:33:30 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event"Melanie A.D. During, Dennis F.A.E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg https://osf.io/fu7rp/Questioning isotopic data from the end-CretaceousRecommended by Christina Belanger based on reviews by Thomas Cullen and 1 anonymous reviewerBeing able to follow the evidence and verify results is critical if we are to be confident in the findings of a scientific study. Here, During et al. (2024) comment on DePalma et al. (2021) and provide a detailed critique of the figures and methods presented that caused them to question the veracity of the isotopic data used to support a spring-time Chicxulub impact at the end-Cretaceous. Given DePalma et al. (2021) did not include a supplemental file containing the original isotopic data, the suspicions rose to accusations of data fabrication (Price, 2022). Subsequent investigations led by DePalma’s current academic institution, The University of Manchester, concluded that the study contained instances of poor research practice that constitute research misconduct, but did not find evidence of fabrication (Price, 2023). Importantly, the overall conclusions of DePalma et al. (2021) are not questioned and both the DePalma et al. (2021) study and a study by During et al. (2022) found that the end-Cretaceous impact occurred in spring. During et al. (2024) also propose some best practices for reporting isotopic data that can help future authors make sure the evidence underlying their conclusions are well documented. Some of these suggestions are commonly reflected in the methods sections of papers working with similar data, but they are not universally required of authors to report. Authors, research mentors, reviewers, and editors, may find this a useful set of guidelines that will help instill confidence in the science that is published. References DePalma, R. A., Oleinik, A. A., Gurche, L. P., Burnham, D. A., Klingler, J. J., McKinney, C. J., Cichocki, F. P., Larson, P. L., Egerton, V. M., Wogelius, R. A., Edwards, N. P., Bergmann, U., and Manning, P. L. (2021). Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 23704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03232-9 During, M. A. D., Smit, J., Voeten, D. F. A. E., Berruyer, C., Tafforeau, P., Sanchez, S., Stein, K. H. W., Verdegaal-Warmerdam, S. J. A., and Van Der Lubbe, J. H. J. L. (2022). The Mesozoic terminated in boreal spring. Nature, 603(7899), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04446-1 During, M. A. D., Voeten, D. F. A. E., and Ahlberg, P. E. (2024). Calibrations without raw data—A response to “Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event.” OSF Preprints, fu7rp, ver. 5, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/fu7rp Price, M. (2022). Paleontologist accused of fraud in paper on dino-killing asteroid. Science, 378(6625), 1155–1157. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg2855 Price, M. (2023). Dinosaur extinction researcher guilty of research misconduct. Science, 382(6676), 1225–1225. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn4967 | Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event" | Melanie A.D. During, Dennis F.A.E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg | <p>A recent paper by DePalma et al. reported that the season of the End-Cretaceous mass extinction was confined to spring/summer on the basis of stable isotope analyses and supplementary observations. An independent study that was concurrently und... | Fossil calibration, Geochemistry, Methods, Vertebrate paleontology | Christina Belanger | 2023-06-22 10:43:31 | View | ||

27 Jan 2020

A simple generative model of trilobite segmentation and growthMelanie J Hopkins https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/zt642Deep insights into trilobite developmentRecommended by Christian Klug based on reviews by Kenneth De Baets and Lukas LaiblTrilobites are arthropods that became extinct at the greatest marine mass extinction over 250 Ma ago. Because of their often bizarre forms, their great diversity and disparity of shapes, they have attracted the interest of researchers and laypersons alike. Due to their calcified exoskeleton, their remains are quite abundant in many marine strata. One particularly interesting aspect, however, is the fossilization of various molting stages. This allows the reconstruction of both juvenile strategies (lecitotrophic versus planktotrophic) and the entire life history of at least some well-documented taxa (e.g., Hughes 2003, 2007; Laibl 2017). For example, life history of trilobites is, based on certain morphological changes, classically subdivided in the three phases protaspis (hatchling, one dorsal shield with few segments with no articulation between), meraspis (juvenile, two and more shields connected by articulations) and holaspis (when the terminal number of thoracic segments is reached). At most molting events, a new skeletal element is added (only in the holaspis, the number of thoracic segments does not change). Nevertheless, many trilobites are known mainly from late meraspid and holaspid stages, because the dorsal shields of the first ontogenetic stages are usually very small and thus often either dissolved or overlooked. An improved understanding of trilobite ontogeny could thus help filling in these gaps in fossil preservation and subsequently, to better understand evolutionary pathways. This is where this paper comes in. In a very clever approach, the New-York-based researcher Melanie Hopkins modeled the growth of these segmented animals (Hopkins 2020). Previous growth models of invertebrates focused on, e.g., mollusks, whose shells grow by accretion. Modelling arthropod ontogeny represented a challenge, which is now overcome by Hopkins' brilliant paper. Her generative growth model is based on empirical data of Aulacopleura koninckii (Barrande, 1846). Hong et al. (2014) and Hughes et al. (2017) documented the ontogeny of this 429 Ma old trilobite species in great detail. In the Silurian of the Barrandian region (Czech Republic), this species is locally very common and all growth stages are well known. I could imagine that the paper of Hughes et al. (2017) planted the seed into Melanie Hopkins’ mind to approach trilobite development in general in a quantitative way with a mathematical approach comparable to the mollusk-research by, e.g., David Raup (1961, 1966) and George McGhee (2015). Hopkins’ growth model requires “a minimum of nine parameters […] to model basic trilobite growth and segmentation, and three additional parameters […] to allow a transition to a new growth gradient for the trunk region during ontogeny” (Hopkins 2020: p. 21). It is now possible to play with parameters such as protaspid size, segment dimensions, segment numbers, etc., in order to estimate changes in body size or morphology. Furthermore, the model could be applied to similarly organized arthropod exoskeletons like many early Cambrian arthropods (e.g., marellomorphs) or even crustaceans (e.g., conchostracans or copepods). Of great interest could also be to assess influences of environmental changes on arthropod ontogeny. Also, her work will help to reconstruct unknown developmental information missing from trilobite species (and possibly other arthropods) and also to explore their morphospace. References Barrande, J. (1846). Notice préliminaire sur le système Silurien et les trilobites de Bohême. Leipzig: Hirschfield.

Hong, P. S., Hughes, N. C., & Sheets, H. D. (2014). Size, shape, and systematics of the Silurian trilobite Aulacopleura koninckii. Journal of Paleontology, 88(6), 1120–1138. doi: 10.1666/13-142 | A simple generative model of trilobite segmentation and growth | Melanie J Hopkins | <p>Generative growth models have been the basis for numerous studies of morphological diversity and evolution. Most work has focused on modeling accretionary growth systems, with much less attention to discrete growth systems. Generative growth mo... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary biology, Invertebrate paleontology, Paleobiology | Christian Klug | 2019-10-06 00:27:25 | View | |

26 Oct 2023

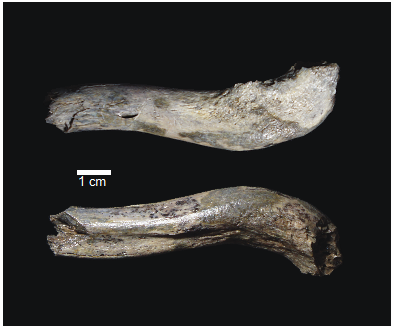

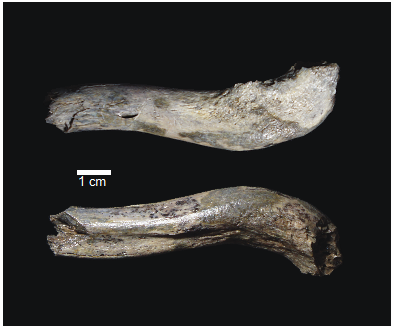

OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai GorgeCatherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656A new method for measuring clavicular curvatureRecommended by Nuria Garcia based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of the hominid clavicle has not been studied in depth by paleoanthropologists given its high morphological variability and the scarcity of complete diagnosable specimens. A nearly complete Nacholapithecus clavicle from Kenya (Senut et al. 2004) together with a fragment from Ardipithecus from the Afar region of Ethiopia (Lovejoy et al. 2009) complete our knowledge of the Miocene record. The Australopithecus collection of clavicles from Eastern and South African Plio-Pleistocene sites is slightly more abundant but mostly represented by fragmentary specimens. The number of fossil clavicles increases for the genus Homo from more recent sites and thus our potential knowledge about the shoulder evolution. In their new contribution, Taylor et al. (2023) present a detailed analysis of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominin clavicle recovered from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). The work goes over previous studies which included clavicles found in the hominid fossil record. The text is accompanied by useful tables of data and a series of excellent photographs. It is a great opportunity to learn its role in the evolution of the hominid shoulder gird as clavicles are relatively poorly preserved in the fossil record compared to other long bones. The study compares the specimen OH 89 with five other hominid clavicles and a sample of 25 modern clavicles, 30 Gorilla, 31 Pan and 7 Papio. The authors propose a new methodology for measuring clavicular curvature using measurements of sternal and acromial curvature, from which an overall curvature measurement is calculated. The study of OH 89 provides good evidence about the hominid who lived 1.8 million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge region. This time period is especially relevant because it can help to understand the morphological changes that occurred between Australopithecus and the appearance of Homo. The authors conclude that OH 89 is the largest of the hominid clavicles included in the analysis. Although they are not able to assign this partial element to species level, this clavicle from Olduvai is at the larger end of the variation observed in Homo sapiens and show similarities to modern humans, especially when analysing the estimated sinusoidal curvature. References Lovejoy, C. O., Suwa, G., Simpson, S. W., Matternes, J. H., and White, T. D. (2009). The Great Divides: Ardipithecus ramidus peveals the postcrania of our last common ancestors with African apes. Science, 326(5949), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1175833 Senut, B., Nakatsukasa, M., Kunimatsu, Y., Nakano, Y., Takano, T., Tsujikawa, H., Shimizu, D., Kagaya, M., and Ishida, H. (2004). Preliminary analysis of Nacholapithecus scapula and clavicle from Nachola, Kenya. Primates, 45(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-003-0073-5 Taylor, C., Masao, F., Njau, J. K., Songita, A. V., and Hlusko, L. J. (2023). OH 89: A newly described ∼1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge. bioRxiv, 526656, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656 | OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge | Catherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko | <p>Objectives: Here, we describe the morphology and geologic context of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. We compare the morphology and clavicular curvature of OH 89 to modern humans, extant apes... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Methods, Morphological evolution, Paleoanthropology, Vertebrate paleontology | Nuria Garcia | 2023-02-08 19:45:01 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jérémy Anquetin

Faysal Bibi

Guillaume Billet

Andrew A. Farke

Franck Guy

Leslea J. Hlusko

Melanie Hopkins

Cynthia V. Looy

Jesús Marugán-Lobón

Ilaria Mazzini

P. David Polly

Caroline A.E. Strömberg