SMITH Heather F.

- Department of Anatomy, Midwestern University, Glendale, United States

- Biomechanics & Functional morphology, Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Fieldwork, Fossil record, Macroevolution, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Paleoanthropology, Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiogeography, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Paleoneurobiology, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology

Recommendations: 0

Reviews: 2

Reviews: 2

Simple shell measurements do not consistently predict habitat in turtles: a reply to Lichtig and Lucas (2017)

Not-so-simple turtle ecomorphology

Recommended by Jordan Mallon based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Donald BrinkmanI am a non-avian dinosaur palaeontologist by trade with a particular interest in their palaeoecology. This can be an endless source of both fascination and frustration. Fascination, because non-avian dinosaurs are quite unlike anything alive today, warranting some use of creative license when imagining them as living animals. Frustration, because the lack of good, extant ecological analogues frequently makes reconstruction of their ancient ecologies an almost insurmountable challenge.

The Canadian Museum of Nature where I work has a good collection of Late Cretaceous turtles. I took an interest in these some years ago because it struck me that, despite the quality of our collection, relatively few people come to study them. I thought, "Someone should work on these. Why not me?" I figured studying a new fossil group would present a fun change of pace and perhaps a more straightforward object of palaeoecological reconstruction. After all, fossil turtles are a lot like living turtles, so how hard can it be? Right?

In 2018, I took a special interest in one recently prepared fossil turtle, which I determined to be a new species of Basilemys (Mallon and Brinkman, 2018). Basilemys held my interest because, although it is a relatively common form, there has been some debate concerning the palaeohabitat of this animal and its closest relatives, the nanhsiungchelyids. Some have argued for an aquatic habitat for these animals; others, for a terrestrial one. It seems that where one comes down on the issue depends on which aspect of ecomorphology is emphasized. If it is on the flat carapace, nanhsiungchelyids must have been aquatic; if it is on the stout feet, terrestrial. This is how I came to appreciate the numerous ecomorphological proxies (e.g., skull shape, shell shape, limb proportions) that are used in turtle palaeoecology and how incongruent they can sometimes be. So much for easy answers!

The present study by Evers et al. is a response to an original piece of research by Lichtig and Lucas (2017), who claimed to be able to use simple shell measurements (carapacial doming and relative plastral width) to accurately deduce/infer the habitats of living turtles and, by extension, fossil ones. In short, they found that terrestrial turtles tend to have more domed carapaces and wider plastra, yielding some unconventional palaeoecological reconstructions of particular stem turtles. Evers et al. take issue with several aspects of this study, including issues of faulty data entry, inappropriate removal of extant taxa from the model, and insufficient accounting for phylogenetic non-independence. By correcting for these overights, they find that the model of Lichtig and Lucas (2017) performs more poorly than advertised and that the palaeoecological classification it produces should be questioned. "The map is not the territory", as Alfred Korzybski put it, and this latest study by Evers et al. serves as an important reminder of that lesson.

Still, even if Lichtig and Lucas's model is overly simplistic, it is true that aquatic turtles, on average, have lower carapaces and narrower plastra, and that they have relatively lower skulls and longer toes. Surely, there is merit in each of these anatomical proxies, even if no single one predicts ecology with total accuracy. I would love to see a model that combines them all. Until then, Evers et al. have inched us closer to knowing what turtle morphology can (and cannot) tell us about habitat.

Thanks to D. Brinkman and H. Smith for their helpful reviews of the manuscript.

References

Evers, S. W., Foth, C., Joyce, W. G., and Hermanson, G. (2024). Simple shell measurements do not consistently predict habitat in turtles: A reply to Lichtig and Lucas (2017). bioRxiv, 586561, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.25.586561

Lichtig, A. J., and Lucas, S. G. (2017). A simple method for inferring habitats of extinct turtles. Palaeoworld, 26(3), 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palwor.2017.02.001

Mallon, J. C., and Brinkman, D. B. (2018). Basilemys morrinensis, a new species of nanhsiungchelyid turtle from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Alberta, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 38(2), e1431922. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2018.1431922

A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA

New baenid turtle material from the Campanian of Wyoming

Recommended by Jérémy Anquetin based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent AdrianThe Baenidae form a diverse extinct clade of exclusively North American paracryptodiran turtles known from the Early Cretaceous to the Eocene (Hay, 1908; Gaffney, 1972; Joyce and Lyson, 2015). Their fossil record was recently extended down to the Berriasian-Valanginian (Joyce et al. 2020), but the group probably originates in the Late Jurassic because it is usually retrieved as the sister group of Pleurosternidae in phylogenetic analyses. However, baenids only became abundant during the Late Cretaceous, when they are restricted in distribution to the western United States, Alberta and Saskatchewan (Joyce and Lyson, 2015).

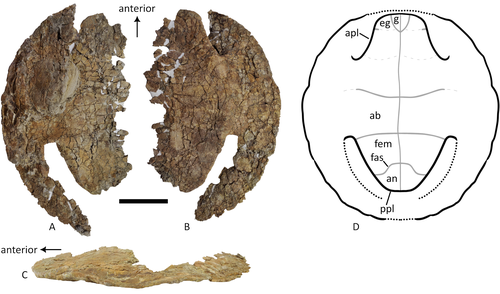

During the Campanian, baenids are abundant in the northern (Alberta, Montana) and southern (Texas, New Mexico, Utah) parts of their range, but in the middle part of this range they are mostly represented by poorly diagnosable shell fragments. In their new contribution, Wu et al. (2023) describe a new articulated baenid specimen from the Campanian Mesaverde Formation of Wyoming. Despite its poor preservation, they are able to confidently assign this partial shell to Neurankylus sp., hence definitively confirming the presence of baenids and Neurankylus in this formation. Incidentally, this new specimen was found in a non-fluvial depositional environment, which would also confirm the interpretation of Neurankylus as a pond turtle (Hutchinson and Archibald, 1986; Sullivan et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2023; see also comments from the second reviewer).

The study of Wu et al. (2023) also includes a detailed account of the state of the fossil when it was discovered and the subsequent extraction and preparation procedures followed by the team. This may seem excessive or out of place to some, but I agree with the authors that such information, when available, should be more commonly integrated into scientific articles describing new fossil specimens. Preparation and restoration can have a significant impact on the perceived morphology. This must be taken into account when working with fossil specimens. The chemicals or products used to treat, prepare, or consolidate the specimens are also important information for long-term curation. Therefore, it is important that such information is recorded and made available for researchers, curators, and preparators.

References

Gaffney, E. S. (1972). The systematics of the North American family Baenidae (Reptilia, Cryptodira). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 147(5), 241–320.

Hay, O. P. (1908). The Fossil Turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.12500

Hutchison, J. H., and Archibald, J. D. (1986). Diversity of turtles across the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary in Northeastern Montana. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(86)90133-1

Joyce, W. G., and Lyson, T. R. (2015). A review of the fossil record of turtles of the clade Baenidae. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 56(2), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.3374/014.058.0105

Joyce, W. G., Rollot, Y., and Cifelli, R. L. (2020). A new species of baenid turtle from the Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation of South Dakota. Fossil Record, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5194/fr-23-1-2020

Sullivan, R. M., Lucas, S. G., Hunt, A. P., and Fritts, T. H. (1988). Color pattern on the selmacryptodiran turtle Neurankylus from the Early Paleocene (Puercan) of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Contributions in Science, 401, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.241286

Wu, K. Y., Heuck, J., Varriale, F. J., and Farke, A. (2023). A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA. PaleorXiv, uk3ac, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3ac