Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

19 Aug 2021

Through a glass darkly, but with more understanding of arthropod originRecommended by Tae-Yoon Park based on reviews by Gerhard Scholtz and Jean VannierArthropods constitute 85% of all described animal species on Earth (Brusca et al., 2016), being the most successful animal phylum at present. This phylum did not even have a shabby beginning. The fossil record shows that they were dominating the sea even in the early Cambrian (Caron and Jackson, 2008; Zhao et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2019). This planet is and has been indeed dominated by arthropods. Within the context of the Big Bang of animal evolution known as the Cambrian Explosion, delving into the origin of arthropods has been one of the all-time fascinating research themes in paleontology, and discussions on the ‘origin’ and ‘early evolution’ of arthropods from the paleontological perspective have not been infrequent (e.g., Budd and Telford, 2009; Edgecombe and Legg, 2014; Daley et al., 2018; Edgecombe, 2020). In this context, Aria (2021) provides an interesting integration of his view on arthropod origin and early evolution. Based on well-preserved Burgess Shale materials, together with other impressive researches mainly with Jean-Bernard Caron (e.g., Aria and Caron, 2015; Caron and Aria, 2017), Cédric Aria made his name known with papers searching for the stem-groups of the two major euarthropod lineages, the Mandibulata and the Chelicerata (Aria and Caron, 2017, 2019), for which (and for his subsequent researches) assembling a large dataset for arthropod phylogeny was inevitable. Subsequently, there have been several major discoveries which could improve our understanding on early arthropod evolution (e.g., Lev and Chipman, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). For Cédric Aria, therefore, this timely presentation of his own perspective on the origin of early evolution of arthropods may have been preordain. This review stands out because it discusses almost all aspects of arthropod origin and early evolution that can be possibly covered by paleontology (many, if not all, of which are still controversial). Some of his views may be considered a brave attempt. For instance, based on the widespread occurrences of suspension feeders, Aria (2021) proposes the early Cambrian “planktonic revolution,” which has been associated rather with the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (Servais et al., 2016). Given the presence of lophotrochozoans and echinoderms in which the presence of planktonic larvae was likely to have been one of the most inclusive features, the “early Cambrian planktonic revolution” might be plausible, but I wonder if including arthropods into the “earlier revolution” can be readily acceptable. Arthropods arose from direct-developing ancestors, and crustaceans (the main group with planktonic larvae) are pretty much derived in the arthropod phylogenetic tree. Trilobites, inarguably the best-studied Cambrian arthropods, for example, began with direct-developing benthic protaspides in the early Cambrian and Miaolingian. The first hint of planktonic protaspides appeared in the Furongian, and it was not until the Tremadocian when such indirect developing protaspides began to be widespread (Park and Kihm, 2015), which complies well with the onset of the ‘Ordovician Planktonic Revolution’ in the Furongian, as suggested by Servais et al. (2016). But in general, this review presents well-organized views worth hearing, and since many of the points are subject to debate, this review could be a friendly manual for those who have similar views, while it could form a fresh ground to attack for those who have disparate views. One of the endless debates in arthropod research comes from the arthropod head problem (Budd, 2002), which centers on the homology of frontal-most appendages in radiodonts, megacheirans, chelicerates, and mandibulates, as well as on the hypostome-labrum complex. Based on recent interesting discoveries of early arthropods from the Chengjiang biota (Aria, 2020; Zeng et al., 2020), Aria (2021) pertinently coined a term ‘cheirae’ for the frontalmost prehensile appendages of radiodonts and megacheirans, implying homology of them. I assume that not all researchers would agree with this though, as well as with his model of hypostome/labrum complex evolution. Notorious disaccords have also occurred around the phylogenetic positions of early arthropods, such as isoxyids, megacheirans, fuxianhuiids, and artiopodans; different research groups have invariably come up with different topologies. Cédric Aria has presented his own topologies (Aria, 2019, 2020), and figure 2 of Aria (2021) summarizes his perspective very well in combination with major character evolutions. What makes this review especially interesting is a courageous discussion about the origin of biramous appendage, a subject that has been only briefly discussed or overlooked in recent literature. In the current mainstream of this debate lies the concept of ‘gilled lobopodians’ (Budd, 1998), which was complicated by the weird two separate rows of lateral flaps of Aegirocassis (Van Roy et al., 2015). Aria (2021) adds an interesting alternative scenario to this: biramicity originated from the split of main limb axis, as seen in the isoxyid Surusicaris (Aria and Caron, 2015). The figure 3d of his review, therefore, is worth giving thoughts for any arthropodologists who are interested in the origin of arthropod legs. It is true that our understanding of the origin and early evolution of arthropods is still in a mist. Nevertheless, we have recently seen advancements, such as those aided by new types of analysis (Liu et al., 2020), the discoveries of new early arthropods with unexpected morphologies (Aria et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020), and the groundbreaking Evo-Devo research (Lev and Chipman, 2020). We will keep jousting on various aspects of the origin and early evolution of arthropods, but for some aspects we are seemingly heading for the final, as implicitly alluded in Aria (2021).

References Aria C (2019). Reviewing the bases for a nomenclatural uniformization of the highest taxonomic levels in arthropods. Geological Magazine 156, 1463–1468. Aria C (2020). Macroevolutionary patterns of body plan canalization in euarthropods. Paleobiology 46, 569–593. doi: 10.1017/pab.2020.36 Aria C (2021). The origin and early evolution of arthropods. PaleorXiv, 4zmey, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/4zmey Aria C and Caron JB (2015). Cephalic and limb anatomy of a new isoxyid from the Burgess Shale and the role of "stem bivalved arthropods" in the disparity of the frontalmost appendage. PLOS ONE 10, e0124979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124979 Aria C and Caron JB (2017). Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan. Nature 545, 89–92. Aria C and Caron JB (2019). A middle Cambrian arthropod with chelicerae and proto-book gills. Nature 573, 586–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1525-4 Aria C, Zhao F, Zeng H, Guo J, and Zhu M (2020). Fossils from South China redefine the ancestral euarthropod body plan. BMC Evolutionary Biology 20, 4. Brusca RC, Moore W, and Shuster SM (2016). Invertebrates. Third edition. Sunderland, Massachusetts U.S.A: Sinauer Associates. isbn: 978-1-60535-375-3 Budd GE (1998). Stem-group arthropods from the Lower Cambrian Sirius Passet fauna of North Greenland. In: Arthropod Relationships. Ed. by Fortey RA and Thomas RH. London, UK: Chapman & Hall, pp. 125–138. Budd GE (2002). A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature 417, 271–275. doi: 10.1038/417271a Budd GE and Telford MJ (2009). The origin and evolution of arthropods. Nature 457, 812–817. doi: 10.1038/Nature07890 Caron JB and Aria C (2017). Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods. BMC Evolutionary Biology 17, 29. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y Caron JB and Jackson DA (2008). Paleoecology of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 258, 222–256. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.023 Daley AC, Antcliffe JB, Drage HB, and Pates S (2018). Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, 5323–5331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719962115 Edgecombe GD (2020). Arthropod origins: Integrating paleontological and molecular evidence. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51, 1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-124437 Edgecombe GD and Legg DA (2014). Origins and early evolution of arthropods. Palaeontology 57, 457–468. Fu D, Tong G, Dai T, Liu W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Cui L, Li L, Yun H, Wu Y, Sun A, Liu C, Pei W, Gaines RR, and Zhang X (2019). The Qingjiang biota—A Burgess Shale–type fossil Lagerstätte from the early Cambrian of South China. Science 363, 1338–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8800 Lev O and Chipman AD (2020). Development of the pre-gnathal segments of the insect head indicates they are not serial homologues of trunk segments. bioRxiv, 2020.09.16.299289. doi: 10.1101/2020.09.16.299289 Liu Y, Ortega-Hernández J, Zhai D, and Hou X (2020). A reduced labrum in a Cambrian great-appendage euarthropod. Current Biology 30, 3057–3061.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.085 Park TYS and Kihm JH (2015). Post-embryonic development of the Early Ordovician (ca. 480 Ma) trilobite Apatokephalus latilimbatus Peng, 1990 and the evolution of metamorphosis. Evolution & Development 17, 289–301. doi: 10.1111/ede.12138 Servais T, Perrier V, Danelian T, Klug C, Martin R, Munnecke A, Nowak H, Nützel A, Vandenbroucke TR, Williams M, and Rasmussen CM (2016). The onset of the ‘Ordovician Plankton Revolution’ in the late Cambrian. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 458, 12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.11.003 Van Roy P, Daley AC, and Briggs DEG (2015). Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. Nature 522, 77–80. doi: 10.1038/nature14256 Zeng H, Zhao F, Niu K, Zhu M, and Huang D (2020). An early Cambrian euarthropod with radiodont-like raptorial appendages. Nature 588, 101–105. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7 Zhao F, Caron JB, Bottjer DJ, Hu S, Yin Z, and Zhu M (2014). Diversity and species abundance patterns of the Early Cambrian (Series 2, Stage 3) Chengjiang Biota from China. Paleobiology 40, 50–69. doi: 10.1666/12056 | The origin and early evolution of arthropods | Cédric Aria | <p style="text-align: justify;">The rise of arthropods is a decisive event in the history of life. Likely the first animals to have established themselves on land and in the air, arthropods have pervaded nearly all ecosystems and have become pilla... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Invertebrate paleontology, Macroevolution, Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Taphonomy, Taxonomy | Tae-Yoon Park | 2021-04-26 13:51:21 | View | |

15 Dec 2022

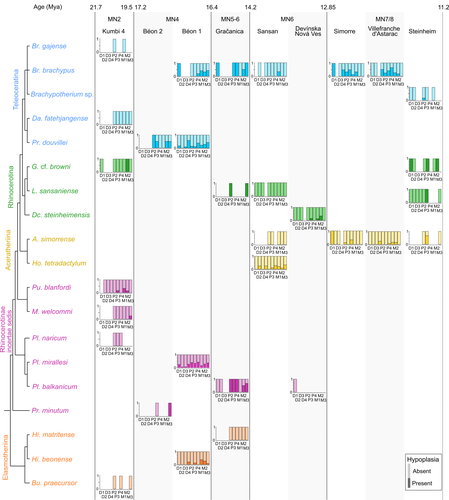

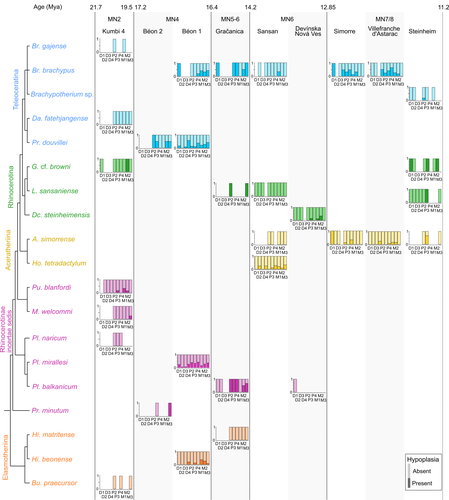

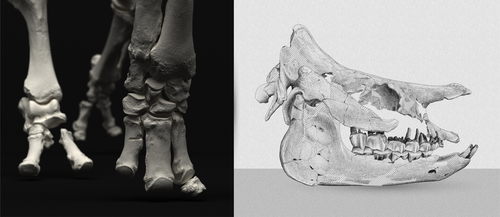

Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: impact of climate changesManon Hullot, Gildas Merceron, Pierre-Olivier Antoine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.06.490903New insights into the palaeoecology of Miocene Eurasian rhinocerotids based on tooth analysisRecommended by Alexandra Houssaye based on reviews by Antigone Uzunidis, Christophe Mallet and Matthew MihlbachlerRhinocerotoidea originated in the Lower Eocene and diversified well during the Cenozoic in Eurasia, North America and Africa. This taxon encompasses a great diversity of ecologies and body proportions and masses. Within this group, the family Rhinocerotidae, which is the only one with extant representatives, appeared in the Late Eocene (Prothero & Schoch, 1989). They were well diversified during the Early and Middle Miocene, whereas they began to decline in both diversity and geographical range after the Miocene, throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, in conjunction with the marked climatic changes (Cerdeño, 1998). In Eurasian Early and Middle Miocene fossil localities, a variety of species are often associated. Therefore, it may be quite difficult to estimate how these large herbivores cohabited and whether competition for food resources is reflected in a diversity of ecological niches. The ecologies of these large mammals are rather poorly known and the detailed study of their teeth could bring new elements of answer. Indeed, if teeth carry a strong phylogenetic signal in mammals, they are also of great interest for ecological studies, and they have the additional advantage of being often numerous in the fossil record. Hullot et al. (2022) analysed both dental microwear texture, as an indicator of dietary preferences, and enamel hypoplasia, to identify stress sensitivity, in a large number of rhinocerotid fossil teeth from nine Neogene (Early to Middle Miocene) localities in Europe and Pakistan. Their aim was to analyse whether fossil species diversity is associated with a diversity of ecologies, and to investigate possible ecological differences between regions and time periods in relation to climate change. Their results show clear differences in time and space between and within species, and suggest that more flexible species are less vulnerable to environmental stressors. Very few studies focus on the palaeocology of Miocene rhinos. This study is therefore a great contribution to the understanding of the evolution of this group.

References Cerdeño, E. (1998). Diversity and evolutionary trends of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 141, 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00003-0 Hullot, M., Merceron, G., and Antoine, P.-O. (2022). Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: Impact of climate changes. BioRxiv, 490903, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.06.490903 Prothero, D. R., and Schoch, R. M. (1989). The evolution of perissodactyls. New York: Oxford University Press. | Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: impact of climate changes | Manon Hullot, Gildas Merceron, Pierre-Olivier Antoine | <p>Major climatic and ecological changes are documented in terrestrial ecosystems during the Miocene epoch. The Rhinocerotidae are a very interesting clade to investigate the impact of these changes on ecology, as they are abundant and diverse in ... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Paleopathology, Vertebrate paleontology | Alexandra Houssaye | 2022-05-09 09:33:30 | View | |

07 Mar 2024

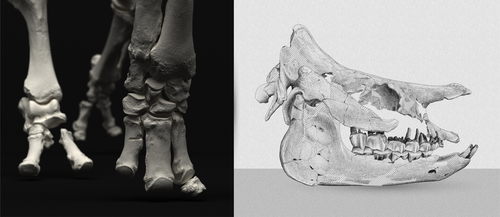

An Early Miocene skeleton of Brachydiceratherium Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratinesAlexander Sizov, Alexey Klementiev, Pierre-Olivier Antoine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.06.498987A Rhino from Lake BaikalRecommended by Faysal Bibi based on reviews by Jérémy Tissier, Panagiotis Kampouridis and Tao Deng based on reviews by Jérémy Tissier, Panagiotis Kampouridis and Tao Deng

As for many groups, such as equids or elephants, the number of living rhinoceros species is just a fraction of their past diversity as revealed by the fossil record. Besides being far more widespread and taxonomically diverse, rhinos also came in a greater variety of shapes and sizes. Some of these – teleoceratines, or so-called ‘hippo-like’ rhinos – had short limbs, barrel-shaped bodies, were often hornless, and might have been semi-aquatic (Prothero et al., 1989; Antoine, 2002). Teleoceratines existed from the Oligocene to the Pliocene, and have been recorded from Eurasia, Africa, and North and Central America. Despite this large temporal and spatial presence, large gaps remain in our knowledge of this group, particularly when it comes to their phylogeny and their relationships to other parts of the rhino tree (Antoine, 2002; Lu et al., 2021). Here, Sizov et al. (2024) describe an almost complete skeleton of a teleoceratine found in 2008 on an island in Lake Baikal in eastern Russia. Dating to the Early Miocene, this wonderfully preserved specimen includes the skull and limb bones, which are described and figured in detail, and which indicate assignment to Brachydiceratherium shanwangense, a species otherwise known only from Shandong in eastern China, some 2000 km to the southeast (Wang, 1965; Lu et al., 2021). The study goes on to present a new phylogenetic analysis of the teleoceratines, the results of which have important implications for the taxonomy of fossil rhinos. Besides confirming the monophyly of Teleoceratina, the phylogeny supports the reassignment of most species previously assigned to Diaceratherium to Brachydiceratherium instead. In a field that is increasingly dominated by analyses of metadata, Sizov et al. (2024) provide a reminder of the importance of fieldwork for the discovery of fossil remains that, sometimes by virtue of a single specimen, can significantly augment our understanding of the evolution and paleobiogeography of extinct species. References Antoine, P.-O. (2002). Phylogénie et évolution des Elasmotheriina (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae). Mémoires du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 188, 1–359. Lu, X., Cerdeño, E., Zheng, X., Wang, S., & Deng, T. (2021). The first Asian skeleton of Diaceratherium from the early Miocene Shanwang Basin (Shandong, China), and implications for its migration route. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences: X, 6, 100074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaesx.2021.100074 Prothero, D. R., Guérin, C., and Manning, E. (1989). The History of the Rhinocerotoidea. In D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (Eds.), The Evolution of Perissodactyls (pp. 322–340). Oxford University Press. Sizov, A., Klementiev, A., & Antoine, P.-O. (2024). An Early Miocene skeleton of Brachydiceratherium Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratines. bioRxiv, 498987, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.06.498987 Wang, B. Y. (1965). A new Miocene aceratheriine rhinoceros of Shanwang, Shandong. Vertebrata Palasiatica, 9, 109–112.

| An Early Miocene skeleton of *Brachydiceratherium* Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratines | Alexander Sizov, Alexey Klementiev, Pierre-Olivier Antoine | <p>Hippo-like rhinocerotids, or teleoceratines, were a conspicuous component of Holarctic Miocene mammalian faunas, but their phylogenetic relationships remain poorly known. Excavations in lower Miocene deposits of the Olkhon Island (Tagay localit... |  | Biostratigraphy, Comparative anatomy, Fieldwork, Paleobiogeography, Paleogeography, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Faysal Bibi | 2022-07-07 15:27:12 | View | |

13 Jul 2023

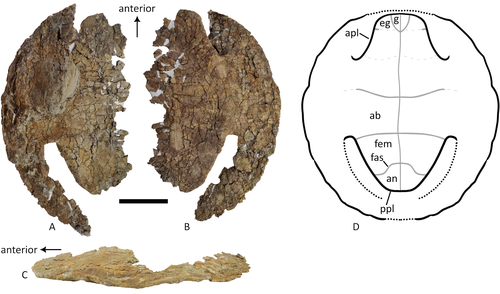

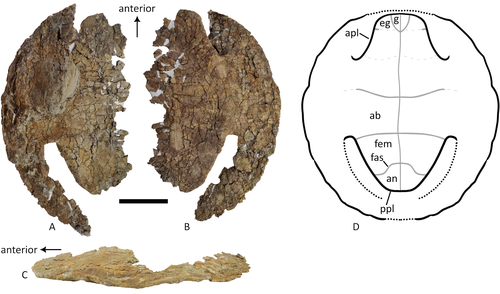

A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USAKa Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3acNew baenid turtle material from the Campanian of WyomingRecommended by Jérémy Anquetin based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian

The Baenidae form a diverse extinct clade of exclusively North American paracryptodiran turtles known from the Early Cretaceous to the Eocene (Hay, 1908; Gaffney, 1972; Joyce and Lyson, 2015). Their fossil record was recently extended down to the Berriasian-Valanginian (Joyce et al. 2020), but the group probably originates in the Late Jurassic because it is usually retrieved as the sister group of Pleurosternidae in phylogenetic analyses. However, baenids only became abundant during the Late Cretaceous, when they are restricted in distribution to the western United States, Alberta and Saskatchewan (Joyce and Lyson, 2015). During the Campanian, baenids are abundant in the northern (Alberta, Montana) and southern (Texas, New Mexico, Utah) parts of their range, but in the middle part of this range they are mostly represented by poorly diagnosable shell fragments. In their new contribution, Wu et al. (2023) describe a new articulated baenid specimen from the Campanian Mesaverde Formation of Wyoming. Despite its poor preservation, they are able to confidently assign this partial shell to Neurankylus sp., hence definitively confirming the presence of baenids and Neurankylus in this formation. Incidentally, this new specimen was found in a non-fluvial depositional environment, which would also confirm the interpretation of Neurankylus as a pond turtle (Hutchinson and Archibald, 1986; Sullivan et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2023; see also comments from the second reviewer). The study of Wu et al. (2023) also includes a detailed account of the state of the fossil when it was discovered and the subsequent extraction and preparation procedures followed by the team. This may seem excessive or out of place to some, but I agree with the authors that such information, when available, should be more commonly integrated into scientific articles describing new fossil specimens. Preparation and restoration can have a significant impact on the perceived morphology. This must be taken into account when working with fossil specimens. The chemicals or products used to treat, prepare, or consolidate the specimens are also important information for long-term curation. Therefore, it is important that such information is recorded and made available for researchers, curators, and preparators. References Gaffney, E. S. (1972). The systematics of the North American family Baenidae (Reptilia, Cryptodira). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 147(5), 241–320. Hay, O. P. (1908). The Fossil Turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.12500 Hutchison, J. H., and Archibald, J. D. (1986). Diversity of turtles across the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary in Northeastern Montana. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(86)90133-1 Joyce, W. G., and Lyson, T. R. (2015). A review of the fossil record of turtles of the clade Baenidae. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 56(2), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.3374/014.058.0105 Joyce, W. G., Rollot, Y., and Cifelli, R. L. (2020). A new species of baenid turtle from the Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation of South Dakota. Fossil Record, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5194/fr-23-1-2020 Sullivan, R. M., Lucas, S. G., Hunt, A. P., and Fritts, T. H. (1988). Color pattern on the selmacryptodiran turtle Neurankylus from the Early Paleocene (Puercan) of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Contributions in Science, 401, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.241286 Wu, K. Y., Heuck, J., Varriale, F. J., and Farke, A. (2023). A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA. PaleorXiv, uk3ac, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3ac | A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA | Ka Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke | <p>The Mesaverde Formation of the Wind River and Bighorn basins of Wyoming preserves a rich yet relatively unstudied terrestrial and marine faunal assemblage dating to the Campanian. To date, turtles within the formation have been represented prim... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiogeography, Vertebrate paleontology | Jérémy Anquetin | 2023-01-16 16:26:43 | View | |

26 Oct 2023

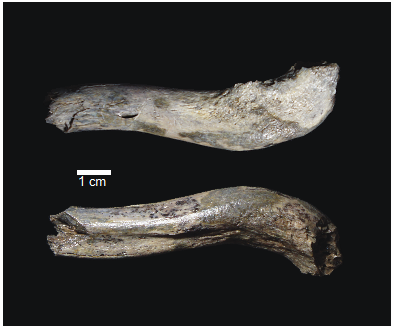

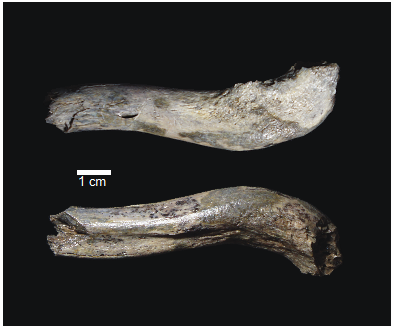

OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai GorgeCatherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656A new method for measuring clavicular curvatureRecommended by Nuria Garcia based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of the hominid clavicle has not been studied in depth by paleoanthropologists given its high morphological variability and the scarcity of complete diagnosable specimens. A nearly complete Nacholapithecus clavicle from Kenya (Senut et al. 2004) together with a fragment from Ardipithecus from the Afar region of Ethiopia (Lovejoy et al. 2009) complete our knowledge of the Miocene record. The Australopithecus collection of clavicles from Eastern and South African Plio-Pleistocene sites is slightly more abundant but mostly represented by fragmentary specimens. The number of fossil clavicles increases for the genus Homo from more recent sites and thus our potential knowledge about the shoulder evolution. In their new contribution, Taylor et al. (2023) present a detailed analysis of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominin clavicle recovered from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). The work goes over previous studies which included clavicles found in the hominid fossil record. The text is accompanied by useful tables of data and a series of excellent photographs. It is a great opportunity to learn its role in the evolution of the hominid shoulder gird as clavicles are relatively poorly preserved in the fossil record compared to other long bones. The study compares the specimen OH 89 with five other hominid clavicles and a sample of 25 modern clavicles, 30 Gorilla, 31 Pan and 7 Papio. The authors propose a new methodology for measuring clavicular curvature using measurements of sternal and acromial curvature, from which an overall curvature measurement is calculated. The study of OH 89 provides good evidence about the hominid who lived 1.8 million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge region. This time period is especially relevant because it can help to understand the morphological changes that occurred between Australopithecus and the appearance of Homo. The authors conclude that OH 89 is the largest of the hominid clavicles included in the analysis. Although they are not able to assign this partial element to species level, this clavicle from Olduvai is at the larger end of the variation observed in Homo sapiens and show similarities to modern humans, especially when analysing the estimated sinusoidal curvature. References Lovejoy, C. O., Suwa, G., Simpson, S. W., Matternes, J. H., and White, T. D. (2009). The Great Divides: Ardipithecus ramidus peveals the postcrania of our last common ancestors with African apes. Science, 326(5949), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1175833 Senut, B., Nakatsukasa, M., Kunimatsu, Y., Nakano, Y., Takano, T., Tsujikawa, H., Shimizu, D., Kagaya, M., and Ishida, H. (2004). Preliminary analysis of Nacholapithecus scapula and clavicle from Nachola, Kenya. Primates, 45(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-003-0073-5 Taylor, C., Masao, F., Njau, J. K., Songita, A. V., and Hlusko, L. J. (2023). OH 89: A newly described ∼1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge. bioRxiv, 526656, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656 | OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge | Catherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko | <p>Objectives: Here, we describe the morphology and geologic context of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. We compare the morphology and clavicular curvature of OH 89 to modern humans, extant apes... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Methods, Morphological evolution, Paleoanthropology, Vertebrate paleontology | Nuria Garcia | 2023-02-08 19:45:01 | View | |

19 Sep 2023

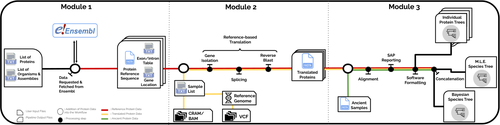

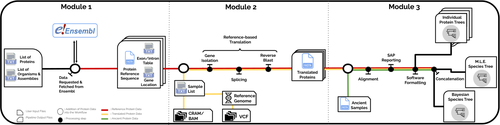

PaleoProPhyler: a reproducible pipeline for phylogenetic inference using ancient proteinsIoannis Patramanis, Jazmín Ramos-Madrigal, Enrico Cappellini, Fernando Racimo https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.12.519721An open-source pipeline to reconstruct phylogenies with paleoproteomic dataRecommended by Leslea Hlusko based on reviews by Katerina Douka and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the most recent technological advances in paleontology enables the characterization of ancient proteins, a new discipline known as palaeoproteomics (Ostrom et al., 2000; Warinner et al., 2022). Palaeoproteomics has superficial similarities with ancient DNA, as both work with ancient molecules, however the former focuses on peptides and the latter on nucleotides. While the study of ancient DNA is more established (e.g., Shapiro et al., 2019), palaeoproteomics is experiencing a rapid diversification of application, from deep time paleontology (e.g., Schroeter et al., 2022) to taxonomic identification of bone fragments (e.g., Douka et al., 2019), and determining genetic sex of ancient individuals (e.g., Lugli et al., 2022). However, as Patramanis et al. (2023) note in this manuscript, tools for analyzing protein sequence data are still in the informal stage, making the application of this methodology a challenge for many new-comers to the discipline, especially those with little bioinformatics expertise. In the spirit of democratizing the field of palaeoproteomics, Patramanis et al. (2023) developed an open-source pipeline, PaleoProPhyler released under a CC-BY license (https://github.com/johnpatramanis/Proteomic_Pipeline). Here, Patramanis et al. (2023) introduce their workflow designed to facilitate the phylogenetic analysis of ancient proteins. This pipeline is built on the methods from earlier studies probing the phylogenetic relationships of an extinct genus of rhinoceros Stephanorhinus (Cappellini et al., 2019), the large extinct ape Gigantopithecus (Welker et al., 2019), and Homo antecessor (Welker et al., 2020). PaleoProPhyler has three interacting modules that initialize, construct, and analyze an input dataset. The authors provide a demonstration of application, presenting a molecular hominid phyloproteomic tree. In order to run some of the analyses within the pipeline, the authors also generated the Hominid Palaeoproteomic Reference Dataset which includes 10,058 protein sequences per individual translated from publicly available whole genomes of extant hominids (orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans) as well as some ancient genomes of Neanderthals and Denisovans. This valuable research resource is also publicly available, on Zenodo (Patramanis et al., 2022). Three reviewers reported positively about the development of this program, noting its importance in advancing the application of palaeoproteomics more broadly in paleontology. References Cappellini, E., Welker, F., Pandolfi, L., Ramos-Madrigal, J., Samodova, D., Rüther, P. L., Fotakis, A. K., Lyon, D., Moreno-Mayar, J. V., Bukhsianidze, M., Rakownikow Jersie-Christensen, R., Mackie, M., Ginolhac, A., Ferring, R., Tappen, M., Palkopoulou, E., Dickinson, M. R., Stafford, T. W., Chan, Y. L., … Willerslev, E. (2019). Early Pleistocene enamel proteome from Dmanisi resolves Stephanorhinus phylogeny. Nature, 574(7776), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1555-y Douka, K., Brown, S., Higham, T., Pääbo, S., Derevianko, A., and Shunkov, M. (2019). FINDER project: Collagen fingerprinting (ZooMS) for the identification of new human fossils. Antiquity, 93(367), e1. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.3 Lugli, F., Nava, A., Sorrentino, R., Vazzana, A., Bortolini, E., Oxilia, G., Silvestrini, S., Nannini, N., Bondioli, L., Fewlass, H., Talamo, S., Bard, E., Mancini, L., Müller, W., Romandini, M., and Benazzi, S. (2022). Tracing the mobility of a Late Epigravettian (~ 13 ka) male infant from Grotte di Pradis (Northeastern Italian Prealps) at high-temporal resolution. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 8104. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12193-6 Ostrom, P. H., Schall, M., Gandhi, H., Shen, T.-L., Hauschka, P. V., Strahler, J. R., and Gage, D. A. (2000). New strategies for characterizing ancient proteins using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 64(6), 1043–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00381-6 Patramanis, I., Ramos-Madrigal, J., Cappellini, E., and Racimo, F. (2022). Hominid Palaeoproteomic Reference Dataset (1.0.1) [dataset]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7333226 Patramanis, I., Ramos-Madrigal, J., Cappellini, E., and Racimo, F. (2023). PaleoProPhyler: A reproducible pipeline for phylogenetic inference using ancient proteins. BioRxiv, 519721, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.12.519721 Schroeter, E. R., Cleland, T. P., and Schweitzer, M. H. (2022). Deep Time Paleoproteomics: Looking Forward. Journal of Proteome Research, 21(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00755 Shapiro, B., Barlow, A., Heintzman, P. D., Hofreiter, M., Paijmans, J. L. A., and Soares, A. E. R. (Eds.). (2019). Ancient DNA: Methods and Protocols (2nd ed., Vol. 1963). Humana, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9176-1 Warinner, C., Korzow Richter, K., and Collins, M. J. (2022). Paleoproteomics. Chemical Reviews, 122(16), 13401–13446. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00703 Welker, F., Ramos-Madrigal, J., Gutenbrunner, P., Mackie, M., Tiwary, S., Rakownikow Jersie-Christensen, R., Chiva, C., Dickinson, M. R., Kuhlwilm, M., De Manuel, M., Gelabert, P., Martinón-Torres, M., Margvelashvili, A., Arsuaga, J. L., Carbonell, E., Marques-Bonet, T., Penkman, K., Sabidó, E., Cox, J., … Cappellini, E. (2020). The dental proteome of Homo antecessor. Nature, 580(7802), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2153-8 Welker, F., Ramos-Madrigal, J., Kuhlwilm, M., Liao, W., Gutenbrunner, P., De Manuel, M., Samodova, D., Mackie, M., Allentoft, M. E., Bacon, A.-M., Collins, M. J., Cox, J., Lalueza-Fox, C., Olsen, J. V., Demeter, F., Wang, W., Marques-Bonet, T., and Cappellini, E. (2019). Enamel proteome shows that Gigantopithecus was an early diverging pongine. Nature, 576(7786), 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1728-8 | PaleoProPhyler: a reproducible pipeline for phylogenetic inference using ancient proteins | Ioannis Patramanis, Jazmín Ramos-Madrigal, Enrico Cappellini, Fernando Racimo | <p>Ancient proteins from fossilized or semi-fossilized remains can yield phylogenetic information at broad temporal horizons, in some cases even millions of years into the past. In recent years, peptides extracted from archaic hominins and long-ex... |  | Evolutionary biology, Paleoanthropology, Paleogenetics & Ancient DNA, Phylogenetics | Leslea Hlusko | 2023-02-24 13:40:12 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event"Melanie A.D. During, Dennis F.A.E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg https://osf.io/fu7rp/Questioning isotopic data from the end-CretaceousRecommended by Christina Belanger based on reviews by Thomas Cullen and 1 anonymous reviewerBeing able to follow the evidence and verify results is critical if we are to be confident in the findings of a scientific study. Here, During et al. (2024) comment on DePalma et al. (2021) and provide a detailed critique of the figures and methods presented that caused them to question the veracity of the isotopic data used to support a spring-time Chicxulub impact at the end-Cretaceous. Given DePalma et al. (2021) did not include a supplemental file containing the original isotopic data, the suspicions rose to accusations of data fabrication (Price, 2022). Subsequent investigations led by DePalma’s current academic institution, The University of Manchester, concluded that the study contained instances of poor research practice that constitute research misconduct, but did not find evidence of fabrication (Price, 2023). Importantly, the overall conclusions of DePalma et al. (2021) are not questioned and both the DePalma et al. (2021) study and a study by During et al. (2022) found that the end-Cretaceous impact occurred in spring. During et al. (2024) also propose some best practices for reporting isotopic data that can help future authors make sure the evidence underlying their conclusions are well documented. Some of these suggestions are commonly reflected in the methods sections of papers working with similar data, but they are not universally required of authors to report. Authors, research mentors, reviewers, and editors, may find this a useful set of guidelines that will help instill confidence in the science that is published. References DePalma, R. A., Oleinik, A. A., Gurche, L. P., Burnham, D. A., Klingler, J. J., McKinney, C. J., Cichocki, F. P., Larson, P. L., Egerton, V. M., Wogelius, R. A., Edwards, N. P., Bergmann, U., and Manning, P. L. (2021). Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 23704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03232-9 During, M. A. D., Smit, J., Voeten, D. F. A. E., Berruyer, C., Tafforeau, P., Sanchez, S., Stein, K. H. W., Verdegaal-Warmerdam, S. J. A., and Van Der Lubbe, J. H. J. L. (2022). The Mesozoic terminated in boreal spring. Nature, 603(7899), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04446-1 During, M. A. D., Voeten, D. F. A. E., and Ahlberg, P. E. (2024). Calibrations without raw data—A response to “Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event.” OSF Preprints, fu7rp, ver. 5, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/fu7rp Price, M. (2022). Paleontologist accused of fraud in paper on dino-killing asteroid. Science, 378(6625), 1155–1157. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg2855 Price, M. (2023). Dinosaur extinction researcher guilty of research misconduct. Science, 382(6676), 1225–1225. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn4967 | Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event" | Melanie A.D. During, Dennis F.A.E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg | <p>A recent paper by DePalma et al. reported that the season of the End-Cretaceous mass extinction was confined to spring/summer on the basis of stable isotope analyses and supplementary observations. An independent study that was concurrently und... | Fossil calibration, Geochemistry, Methods, Vertebrate paleontology | Christina Belanger | 2023-06-22 10:43:31 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jérémy Anquetin

Faysal Bibi

Guillaume Billet

Andrew A. Farke

Franck Guy

Leslea J. Hlusko

Melanie Hopkins

Cynthia V. Looy

Jesús Marugán-Lobón

Ilaria Mazzini

P. David Polly

Caroline A.E. Strömberg