Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Mar 2024

Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event"Melanie A.D. During, Dennis F.A.E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg https://osf.io/fu7rp/Questioning isotopic data from the end-CretaceousRecommended by Christina Belanger based on reviews by Thomas Cullen and 1 anonymous reviewerBeing able to follow the evidence and verify results is critical if we are to be confident in the findings of a scientific study. Here, During et al. (2024) comment on DePalma et al. (2021) and provide a detailed critique of the figures and methods presented that caused them to question the veracity of the isotopic data used to support a spring-time Chicxulub impact at the end-Cretaceous. Given DePalma et al. (2021) did not include a supplemental file containing the original isotopic data, the suspicions rose to accusations of data fabrication (Price, 2022). Subsequent investigations led by DePalma’s current academic institution, The University of Manchester, concluded that the study contained instances of poor research practice that constitute research misconduct, but did not find evidence of fabrication (Price, 2023). Importantly, the overall conclusions of DePalma et al. (2021) are not questioned and both the DePalma et al. (2021) study and a study by During et al. (2022) found that the end-Cretaceous impact occurred in spring. During et al. (2024) also propose some best practices for reporting isotopic data that can help future authors make sure the evidence underlying their conclusions are well documented. Some of these suggestions are commonly reflected in the methods sections of papers working with similar data, but they are not universally required of authors to report. Authors, research mentors, reviewers, and editors, may find this a useful set of guidelines that will help instill confidence in the science that is published. References DePalma, R. A., Oleinik, A. A., Gurche, L. P., Burnham, D. A., Klingler, J. J., McKinney, C. J., Cichocki, F. P., Larson, P. L., Egerton, V. M., Wogelius, R. A., Edwards, N. P., Bergmann, U., and Manning, P. L. (2021). Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 23704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03232-9 During, M. A. D., Smit, J., Voeten, D. F. A. E., Berruyer, C., Tafforeau, P., Sanchez, S., Stein, K. H. W., Verdegaal-Warmerdam, S. J. A., and Van Der Lubbe, J. H. J. L. (2022). The Mesozoic terminated in boreal spring. Nature, 603(7899), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04446-1 During, M. A. D., Voeten, D. F. A. E., and Ahlberg, P. E. (2024). Calibrations without raw data—A response to “Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event.” OSF Preprints, fu7rp, ver. 5, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/fu7rp Price, M. (2022). Paleontologist accused of fraud in paper on dino-killing asteroid. Science, 378(6625), 1155–1157. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg2855 Price, M. (2023). Dinosaur extinction researcher guilty of research misconduct. Science, 382(6676), 1225–1225. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn4967 | Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event" | Melanie A.D. During, Dennis F.A.E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg | <p>A recent paper by DePalma et al. reported that the season of the End-Cretaceous mass extinction was confined to spring/summer on the basis of stable isotope analyses and supplementary observations. An independent study that was concurrently und... | Fossil calibration, Geochemistry, Methods, Vertebrate paleontology | Christina Belanger | 2023-06-22 10:43:31 | View | ||

30 Oct 2019

The Morrison Formation Sauropod Consensus: A freely accessible online spreadsheet of collected sauropod specimens, their housing institutions, contents, references, localities, and other potentially useful informationEmanuel Tschopp, John A. Whitlock, D. Cary Woodruff, John R. Foster, Roberto Lei, Simone Giovanardi https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/ydvraSauropods under one (very high) roofRecommended by Jordan Mallon based on reviews by Kenneth Carpenter and Femke HolwerdaFossils get around. Any one fossil locality might be sampled by several collectors from as many institutions around the world. Alternatively, a single collector might heavily sample a site, and sell or trade parts of their collection to other institutions, scattering the fossils far and wide. These practices have the advantage of making fossils from any one locality available to researchers across the globe. However, they also have the disadvantage that, in order to systematically survey any one species, a researcher must follow innumerable trails of breadcrumb to get to where the relevant materials are held. This is true of many famous fossil localities, such as the Eocene Green River Formation in the USA, the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Morocco, or the Devonian Miguasha cliffs of Canada. It is especially true of the Upper Jurassic deposits of the Morrison Formation in the western USA, which have yielded an impressive assemblage of megaherbivorous sauropod dinosaurs over the last 150 years. Today, these bones are to be found in museums not just in the USA, but also in Canada, Argentina, Japan, Australia, Malaysia, South Africa, and throughout Europe. Trawling museum databases in search of sauropod material from the Morrison Formation can therefore be a daunting task, never mind traveling the globe to actually study them. A new paper by Tschopp et al. (2019) seeks to ease the burden on sauropod researchers by introducing a database of Morrison Formation sauropods, consisting of over 3000 specimens housed in nearly 40 institutions around the world. The authors are themselves sauropod workers and, having suffered first-hand the plight of studying material from the Morrison Formation, came up with a solution to the problem of keeping track of it all. The database is founded largely on material personally seen by the authors, supplemented by information from the literature and museum catalogs. The database further provides information on bone representation, ontogeny, locality details, and fine-scale stratigraphy, among other fields. Like any database, it is a living document that will continue to grow as new finds are made. Tschopp et al. (2019) have wisely chosen to allow others to contribute to the listing, but changes must first be vetted for accuracy. This product represents 10 years of work, and I have little doubt that it will be well-received by those of us who work on dinosaurs. Speaking personally, my PhD research on megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Canada led me to institutions in Canada, the USA, and the UK, and further stops to Spain and Argentina would have been beneficial, if affordable. Planning for this work would have been greatly assisted by a database like the one provided us by Tschopp et al. (2019). Many a future graduate student will undoubtedly owe them a debt of gratitude. References Tschopp, E., Whitlock, J. A., Woodruff, D. C., Foster, J. R., Lei, R., & Giovanardi, S. (2019). The Morrison Formation Sauropod Consensus: A freely accessible online spreadsheet of collected sauropod specimens, their housing institutions, contents, references, localities, and other potentially useful information. PaleorXiv, version 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/ydvra | The Morrison Formation Sauropod Consensus: A freely accessible online spreadsheet of collected sauropod specimens, their housing institutions, contents, references, localities, and other potentially useful information | Emanuel Tschopp, John A. Whitlock, D. Cary Woodruff, John R. Foster, Roberto Lei, Simone Giovanardi | <p>The Morrison Formation has been explored for dinosaurs for more than 150 years, in particular for large sauropod skeletons to be mounted in museum exhibits around the world. Several long-term campaigns to the Jurassic West of the United States ... |  | Fossil record, Methods, Paleobiodiversity, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology | Jordan Mallon | 2019-07-19 16:13:45 | View | |

23 Apr 2021

The record of Deinotheriidae from the Miocene of the Swiss Jura Mountains (Jura Canton, Switzerland)Fanny Gagliardi, Olivier Maridet, Damien Becker https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.10.244061The fossil record of deinotheres in the Jura Mountains and the specific diversity of European deinotheriidsRecommended by Lionel Hautier based on reviews by Martin Pickford and 1 anonymous reviewerProboscideans belong to the Afrotheria, a superorder of mammals with an African origin, which was recently recognized based on molecular data (see review in Asher et al., 2009). The fossil record of Proboscidea is well documented and shows that an important part of their evolutionary history took place in Africa, with their representatives inhabiting the continent for at least 60 million years (Gheerbrant, 2009). However, proboscideans also proved to be great travellers, and a flourishing diversity of proboscidean forms colonized most of the continents of the planet, including Europe, from where they have since completely disappeared. Nowadays, Loxodonta africana, L. cyclotis, and Elephas maximus are flagship species of the African and Asian faunas, but they only represent a minor part of the modern mammalian diversity. In contrast, their ancient relatives seemed to be relatively abundant in past ecosystems (Sanders et al., 2010), which raised a number of interesting, but challenging, questions relative to the structure and evolution of ancient megaherbivore communities (Calandra et al., 2008). Among proboscideans, deinotheres represent a special case. Their morphology clearly departs from that of other groups, notably in displaying distinctive downward curving lower tusks. Compared to their successful sister group the elephantiforms (i.e., all elephant-like proboscideans closely related to modern elephants; sensu Tassy, 1994), deinotheriids are often regarded as the poor sibling of the Proboscidea for showing a relatively low specific diversity and displaying a reduced morphological variability. In fact, many grey areas still exist regarding the evolution of this unique family. In their article, Gagliardi et al. (2021) revised the material of deinotheres recovered in the Miocene sands of the Swiss Jura Mountains. They described for the first time the material attributed to Prodeinotherium bavaricum and Deinotherium giganteum from the Delémont valley, and reported the presence of a third species, Deinotherium levius, from the locality of Charmoille in Ajoie. Based on comparisons made on specimens recovered from middle to the late Miocene localities, the authors discussed the potential link between the mode and tempo of deinothere dispersions and the evolution environmental and climatic conditions in Western and Eastern Europe during the Miocene. They also considered the evolution of ecological specializations in the group, especially with regard to size increase. Gagliardi et al. (2021) proposed to follow the two genera/five species concept (i.e., P. cuvieri, P. bavaricum, D. levius, D. giganteum, and D. proavum), which implies the co-existence of several deinothere species in Europe. The latter hypothesis contrasts with the recognition of a single African Deinotherium species (i.e., D. bozasi) in deposits dated from the late Miocene to the early Pleistocene (Sanders et al., 2010). Such a co-existence of European species was and still is debated; it was here questioned by both reviewers. However, as acknowledged by the authors, only an extensive revision of the material of all recognized species, in Europe and worldwide, will enable to shed more light on the deinothere morphological variability and specific diversity. There is no doubt that such a revision would have a profound impact on our view of the evolution of this enigmatic group.

References Asher, R. J., Bennett, N., & Lehmann, T. (2009). The new framework for understanding placental mammal evolution. BioEssays, 31(8), 853–864. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900053 Calandra, I., Göhlich, U. B., & Merceron, G. (2008). How could sympatric megaherbivores coexist? Example of niche partitioning within a proboscidean community from the Miocene of Europe. Naturwissenschaften, 95(9), 831–838. doi: 10.1007/s00114-008-0391-y Gagliardi, F., Maridet, O., & Becker, D. (2021). The record of Deinotheriidae from the Miocene of the Swiss Jura Mountains (Jura Canton, Switzerland). BioRxiv, 244061, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.1101/2020.08.10.244061 Gheerbrant, E. (2009). Paleocene emergence of elephant relatives and the rapid radiation of African ungulates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10717–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900251106 Sanders, W. J., Gheerbrant, E., Harris, J. M., Saegusa, H., & Delmer, C. (2010). Proboscidea. In L. Werdelin & W. J. Sanders (Eds.), Cenozoic Mammals of Africa (pp. 161–251). Berkeley: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/california/9780520257214.003.0015 Tassy, P. (1994). Origin and differentiation of the Elephantiformes (Mammalia, Proboscidea). Verhandlungen Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg, 34, 73–94. | The record of Deinotheriidae from the Miocene of the Swiss Jura Mountains (Jura Canton, Switzerland) | Fanny Gagliardi, Olivier Maridet, Damien Becker | <p>The Miocene sands of the Swiss Jura Mountains, long exploited in quarries for the construction industry, have yielded abundant fossil remains of large mammals. Among Deinotheriidae (Proboscidea), two species, Prodeinotherium bavaricum and Deino... |  | Fossil record, Paleobiogeography, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology | Lionel Hautier | 2020-08-11 10:17:38 | View | |

01 Oct 2021

Ammonoid taxonomy with supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithmsFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/ewkx9Performance of machine-learning approaches in identifying ammonoid species based on conch propertiesRecommended by Kenneth De Baets based on reviews by Jérémie Bardin and 1 anonymous reviewerThere are less and less experts on taxonomy of particular groups particularly among early career paleontologists and (paleo)biologists – this also includes ammonoid cephalopods. Techniques cannot replace this taxonomic expertise (Engel et al. 2021) but machine learning approaches can make taxonomy more efficient, reproducible as well as passing it over more sustainable. Initially ammonoid taxonomy was a black box with small differences sometimes sufficient to erect different species as well as really idiosyncratic groupings of superficially similar specimens (see De Baets et al. 2015 for a review). In the meantime, scientists have embraced more quantitative assessments of conch shape and morphology more generally (see Klug et al. 2015 for a more recent review). The approaches still rely on important but time-intensive collection work and seeing through daisy chains of more or less accessible papers and monographs without really knowing how these approaches perform (other than expert opinion). In addition, younger scientists are usually trained by more experienced scientists, but this practice is becoming more and more difficult which makes it difficult to resolve the taxonomic gap. This relates to the fact that less and less experienced researchers with this kind of expertise get employed as well as graduate students or postdocs choosing different research or job avenues after their initial training effectively leading to a leaky pipeline and taxonomic impediment. Robust taxonomy and stratigraphy is the basis for all other studies we do as paleontologists/paleobiologists so Foxon (2021) represents the first step to use supervised and unsupervised machine-learning approaches and test their efficiency on ammonoid conch properties. This pilot study demonstrates that machine learning approaches can be reasonably accurate (60-70%) in identifying ammonoid species (Foxon, 2021) – at least similar to that in other mollusk taxa (e.g., Klinkenbuß et al. 2020) - and might also be interesting to assist in cases where more traditional methods are not feasible. Novel approaches might even allow to further approve the accuracy as has been demonstrated for other research objects like pollen (Romero et al. 2020). Further applying of machine learning approaches on larger datasets and additional morphological features (e.g., suture line) are now necessary in order to test and improve the robustness of these approaches for ammonoids as well as test their performance more broadly within paleontology.

References De Baets K, Bert D, Hoffmann R, Monnet C, Yacobucci M, and Klug C (2015). Ammonoid intraspecific variability. In: Ammonoid Paleobiology: From anatomy to ecology. Ed. by Klug C, Korn D, De Baets K, Kruta I, and Mapes R. Vol. 43. Topics in Geobiology. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 359–426. Engel MS, Ceríaco LMP, Daniel GM, Dellapé PM, Löbl I, Marinov M, Reis RE, Young MT, Dubois A, Agarwal I, Lehmann A. P, Alvarado M, Alvarez N, Andreone F, Araujo-Vieira K, Ascher JS, Baêta D, Baldo D, Bandeira SA, Barden P, Barrasso DA, Bendifallah L, Bockmann FA, Böhme W, Borkent A, Brandão CRF, Busack SD, Bybee SM, Channing A, Chatzimanolis S, Christenhusz MJM, Crisci JV, D’elía G, Da Costa LM, Davis SR, De Lucena CAS, Deuve T, Fernandes Elizalde S, Faivovich J, Farooq H, Ferguson AW, Gippoliti S, Gonçalves FMP, Gonzalez VH, Greenbaum E, Hinojosa-Díaz IA, Ineich I, Jiang J, Kahono S, Kury AB, Lucinda PHF, Lynch JD, Malécot V, Marques MP, Marris JWM, Mckellar RC, Mendes LF, Nihei SS, Nishikawa K, Ohler A, Orrico VGD, Ota H, Paiva J, Parrinha D, Pauwels OSG, Pereyra MO, Pestana LB, Pinheiro PDP, Prendini L, Prokop J, Rasmussen C, Rödel MO, Rodrigues MT, Rodríguez SM, Salatnaya H, Sampaio Í, Sánchez-García A, Shebl MA, Santos BS, Solórzano-Kraemer MM, Sousa ACA, Stoev P, Teta P, Trape JF, Dos Santos CVD, Vasudevan K, Vink CJ, Vogel G, Wagner P, Wappler T, Ware JL, Wedmann S, and Zacharie CK (2021). The taxonomic impediment: a shortage of taxonomists, not the lack of technical approaches. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 193, 381–387. doi: 10. 1093/zoolinnean/zlab072 Foxon F (2021). Ammonoid taxonomy with supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithms. PaleorXiv ewkx9, ver. 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/ewkx9 Klinkenbuß D, Metz O, Reichert J, Hauffe T, Neubauer TA, Wesselingh FP, and Wilke T (2020). Performance of 3D morphological methods in the machine learning assisted classification of closely related fossil bivalve species of the genus Dreissena. Malacologia 63, 95. doi: 10.4002/040.063.0109 Klug C, Korn D, Landman NH, Tanabe K, De Baets K, and Naglik C (2015). Ammonoid conchs. In: Ammonoid Paleobiology: From anatomy to ecology. Ed. by Klug C, Korn D, De Baets K, Kruta I, and Mapes RH. Vol. 43. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 3–24. Romero IC, Kong S, Fowlkes CC, Jaramillo C, Urban MA, Oboh-Ikuenobe F, D’Apolito C, and Punyasena SW (2020). Improving the taxonomy of fossil pollen using convolutional neural networks and superresolution microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 28496–28505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007324117 | Ammonoid taxonomy with supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithms | Floe Foxon | <p>Ammonoid identification is crucial to biostratigraphy, systematic palaeontology, and evolutionary biology, but may prove difficult when shell features and sutures are poorly preserved. This necessitates novel approaches to ammonoid taxonomy. Th... |  | Invertebrate paleontology, Taxonomy | Kenneth De Baets | Jérémie Bardin | 2021-01-06 11:48:35 | View |

20 Oct 2020

Evidence of high Sr/Ca in a Middle Jurassic murolith coccolith speciesBaptiste Suchéras-Marx, Fabienne Giraud, Alexandre Simionovici, Rémi Tucoulou, Isabelle Daniel https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/dcfuqNew results and challenges in Sr/Ca studies on Jurassic coccolithophoridsRecommended by Antonino Briguglio based on reviews by Kenneth De Baets and 1 anonymous reviewerThis interesting publication by Suchéras-Marx et al. (2020) highlights peculiar aspects of geochemistry in nannofossils, specifically coccolithophorids. One of the main application of geochemistry on fossil shells is to get hints on the physiology of such extinct taxa. Here, the authors try to get information on the calcification mechanism and processes in Jurassic coccoliths. Coccoliths build a test made of calcium carbonate and one of the most common geochemical proxies used for this fossil group is the Sr/Ca ratio. This isotopic ratio has good chances to be successfully used as a robust proxy for paleoenvironmental reconstruction, but, concerning Jurassic coccoliths things seem to be not straightforward. The authors managed to compare the isotopic value of Sr/Ca measured on Jurassic coccoliths from different taxonomic groups: the murolith Crepidolithus crassus and the placoliths Watznaueria contracta and Discorhabdus striatus. The results they got clearly show that the Sr/Ca ratio cannot be used as a universal proxy because these species exhibit very different values despite coming from the same stratigraphic level and having undergone minimal diagenetic modification. Data seem to point to a Sr/Ca ratio up to 10 times higher in the murolith species than in the placolith taxa (Suchéras-Marx et al., 2020). One of the explanation given here takes advantage of modern coccolith data and hints to specific polysaccharides that would control the growth of the long R unit in the murolith species. As always, there is plenty of space for additional research, possibly on modern taxa, to sort out the scientific questions that arise from this work. References Suchéras-Marx, B., Giraud, F., Simionovici, A., Tucoulou, R., & Daniel, I. (2020). Evidence of high Sr/Ca in a Middle Jurassic murolith coccolith species. PaleorXiv, dcfuq, version 7, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/dcfuq | Evidence of high Sr/Ca in a Middle Jurassic murolith coccolith species | Baptiste Suchéras-Marx, Fabienne Giraud, Alexandre Simionovici, Rémi Tucoulou, Isabelle Daniel | <p>Paleoceanographical reconstructions are often based on microfossil geochemical analyses. Coccoliths are the most ancient, abundant and continuous record of pelagic photic zone calcite producer organisms. Hence, they could be valuable substrates... |  | Microfossils, Micropaleontology, Nanofossils | Antonino Briguglio | 2020-05-18 16:11:35 | View | |

13 Jul 2023

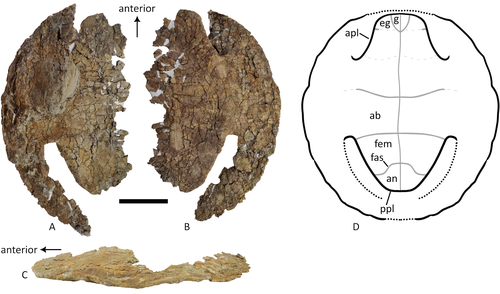

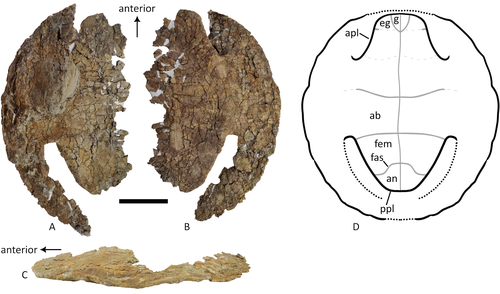

A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USAKa Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3acNew baenid turtle material from the Campanian of WyomingRecommended by Jérémy Anquetin based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian

The Baenidae form a diverse extinct clade of exclusively North American paracryptodiran turtles known from the Early Cretaceous to the Eocene (Hay, 1908; Gaffney, 1972; Joyce and Lyson, 2015). Their fossil record was recently extended down to the Berriasian-Valanginian (Joyce et al. 2020), but the group probably originates in the Late Jurassic because it is usually retrieved as the sister group of Pleurosternidae in phylogenetic analyses. However, baenids only became abundant during the Late Cretaceous, when they are restricted in distribution to the western United States, Alberta and Saskatchewan (Joyce and Lyson, 2015). During the Campanian, baenids are abundant in the northern (Alberta, Montana) and southern (Texas, New Mexico, Utah) parts of their range, but in the middle part of this range they are mostly represented by poorly diagnosable shell fragments. In their new contribution, Wu et al. (2023) describe a new articulated baenid specimen from the Campanian Mesaverde Formation of Wyoming. Despite its poor preservation, they are able to confidently assign this partial shell to Neurankylus sp., hence definitively confirming the presence of baenids and Neurankylus in this formation. Incidentally, this new specimen was found in a non-fluvial depositional environment, which would also confirm the interpretation of Neurankylus as a pond turtle (Hutchinson and Archibald, 1986; Sullivan et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2023; see also comments from the second reviewer). The study of Wu et al. (2023) also includes a detailed account of the state of the fossil when it was discovered and the subsequent extraction and preparation procedures followed by the team. This may seem excessive or out of place to some, but I agree with the authors that such information, when available, should be more commonly integrated into scientific articles describing new fossil specimens. Preparation and restoration can have a significant impact on the perceived morphology. This must be taken into account when working with fossil specimens. The chemicals or products used to treat, prepare, or consolidate the specimens are also important information for long-term curation. Therefore, it is important that such information is recorded and made available for researchers, curators, and preparators. References Gaffney, E. S. (1972). The systematics of the North American family Baenidae (Reptilia, Cryptodira). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 147(5), 241–320. Hay, O. P. (1908). The Fossil Turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.12500 Hutchison, J. H., and Archibald, J. D. (1986). Diversity of turtles across the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary in Northeastern Montana. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(86)90133-1 Joyce, W. G., and Lyson, T. R. (2015). A review of the fossil record of turtles of the clade Baenidae. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 56(2), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.3374/014.058.0105 Joyce, W. G., Rollot, Y., and Cifelli, R. L. (2020). A new species of baenid turtle from the Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation of South Dakota. Fossil Record, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5194/fr-23-1-2020 Sullivan, R. M., Lucas, S. G., Hunt, A. P., and Fritts, T. H. (1988). Color pattern on the selmacryptodiran turtle Neurankylus from the Early Paleocene (Puercan) of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Contributions in Science, 401, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.241286 Wu, K. Y., Heuck, J., Varriale, F. J., and Farke, A. (2023). A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA. PaleorXiv, uk3ac, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3ac | A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA | Ka Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke | <p>The Mesaverde Formation of the Wind River and Bighorn basins of Wyoming preserves a rich yet relatively unstudied terrestrial and marine faunal assemblage dating to the Campanian. To date, turtles within the formation have been represented prim... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiogeography, Vertebrate paleontology | Jérémy Anquetin | 2023-01-16 16:26:43 | View | |

15 Dec 2022

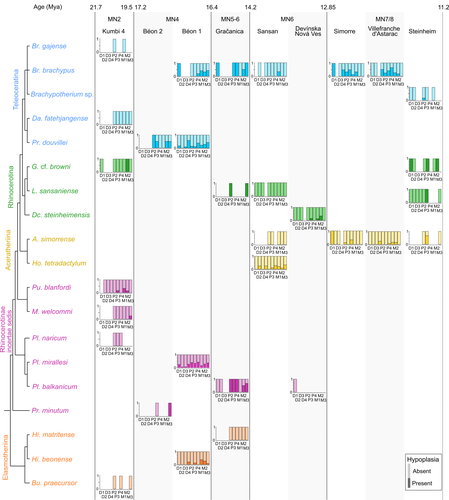

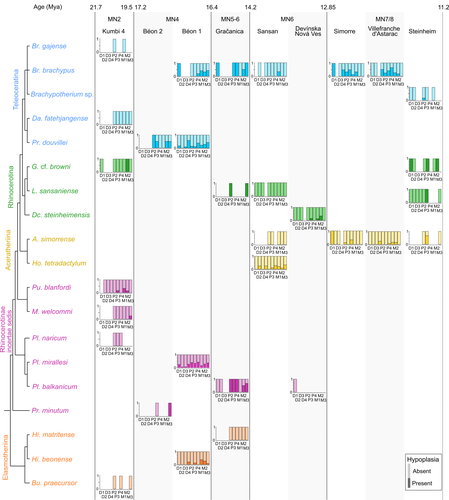

Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: impact of climate changesManon Hullot, Gildas Merceron, Pierre-Olivier Antoine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.06.490903New insights into the palaeoecology of Miocene Eurasian rhinocerotids based on tooth analysisRecommended by Alexandra Houssaye based on reviews by Antigone Uzunidis, Christophe Mallet and Matthew MihlbachlerRhinocerotoidea originated in the Lower Eocene and diversified well during the Cenozoic in Eurasia, North America and Africa. This taxon encompasses a great diversity of ecologies and body proportions and masses. Within this group, the family Rhinocerotidae, which is the only one with extant representatives, appeared in the Late Eocene (Prothero & Schoch, 1989). They were well diversified during the Early and Middle Miocene, whereas they began to decline in both diversity and geographical range after the Miocene, throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, in conjunction with the marked climatic changes (Cerdeño, 1998). In Eurasian Early and Middle Miocene fossil localities, a variety of species are often associated. Therefore, it may be quite difficult to estimate how these large herbivores cohabited and whether competition for food resources is reflected in a diversity of ecological niches. The ecologies of these large mammals are rather poorly known and the detailed study of their teeth could bring new elements of answer. Indeed, if teeth carry a strong phylogenetic signal in mammals, they are also of great interest for ecological studies, and they have the additional advantage of being often numerous in the fossil record. Hullot et al. (2022) analysed both dental microwear texture, as an indicator of dietary preferences, and enamel hypoplasia, to identify stress sensitivity, in a large number of rhinocerotid fossil teeth from nine Neogene (Early to Middle Miocene) localities in Europe and Pakistan. Their aim was to analyse whether fossil species diversity is associated with a diversity of ecologies, and to investigate possible ecological differences between regions and time periods in relation to climate change. Their results show clear differences in time and space between and within species, and suggest that more flexible species are less vulnerable to environmental stressors. Very few studies focus on the palaeocology of Miocene rhinos. This study is therefore a great contribution to the understanding of the evolution of this group.

References Cerdeño, E. (1998). Diversity and evolutionary trends of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 141, 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00003-0 Hullot, M., Merceron, G., and Antoine, P.-O. (2022). Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: Impact of climate changes. BioRxiv, 490903, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.06.490903 Prothero, D. R., and Schoch, R. M. (1989). The evolution of perissodactyls. New York: Oxford University Press. | Spatio-temporal diversity of dietary preferences and stress sensibilities of early and middle Miocene Rhinocerotidae from Eurasia: impact of climate changes | Manon Hullot, Gildas Merceron, Pierre-Olivier Antoine | <p>Major climatic and ecological changes are documented in terrestrial ecosystems during the Miocene epoch. The Rhinocerotidae are a very interesting clade to investigate the impact of these changes on ecology, as they are abundant and diverse in ... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Paleopathology, Vertebrate paleontology | Alexandra Houssaye | 2022-05-09 09:33:30 | View | |

Today

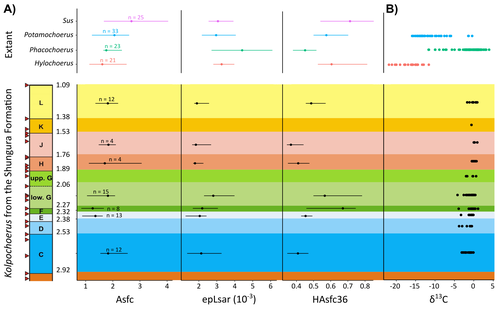

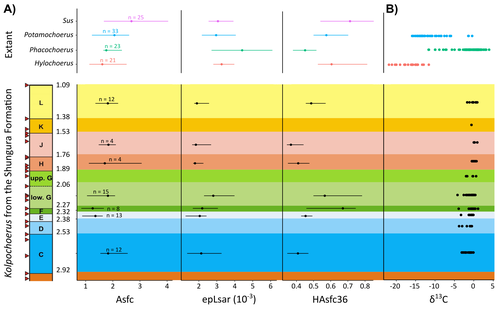

New insights on feeding habits of Kolpochoerus from the Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) using dental microwear texture analysisMargot Louail, Antoine Souron, Gildas Merceron, Jean-Renaud Boisserie https://osf.io/preprints/paleorxiv/dbgtpDental microwear texture analysis of suid teeth from the Shungura Formation of the Omo Valley, EthiopiaRecommended by Denise Su based on reviews by Daniela E. Winkler and Kari PrassackSuidae are well-represented in Plio-Pleistocene African hominin sites and are particularly important for biochronological assessments. Their ubiquity in hominin sites combined with multiple appearances of what appears to be graminivorous adaptations in the lineage (Harris & White, 1979) suggest that they have the potential to contribute to our understanding of Plio-Pleistocene paleoenvironments. While they have been generally understudied in this respect, there has been recent focus on their diets to understand the paleoenvironments of early hominin habitats. Of particular interest is Kolpochoerus, one of the most abundant suid genera in the Plio-Pleistocene with a wide geographic distribution and diverse dental morphologies (Harris & White, 1979). In this study, Louail et al. (2024) present the results of the first dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA) conducted on suids from the Shungura Formation of the Omo Valley, an important Plio-Pleistocene hominin site that records an almost continuous sedimentary record from ca. 3.75 Ma to 1.0 Ma (Heinzelin 1983; McDougall et al., 2012; Kidane et al., 2014). Dental microwear is one of the main proxies in understanding diet in fossil mammals, particularly herbivores, and DMTA has been shown to be effective in differentiating inter- and intra-species dietary differences (e.g., Scott et al., 2006; 2012; Merceron et al., 2010). However, only a few studies have applied this method to extinct suids (Souron et al., 2015; Ungar et al., 2020), making this study especially pertinent for those interested in suid dietary evolution or hominin paleoecology. In addition to examining DMT variations of Kolpochoerus specimens from Omo, Louail et al. (2024) also expanded the modern comparative data set to include larger samples of African suids with different diets from herbivores to omnivores to better interpret the fossil data. They found that DMTA distinguishes between extant suid taxa, reflecting differences in diet, indicating that DMT can be used to examine the diets of fossil suids. The results suggest that Kolpochoerus at Omo had a substantially different diet from any extant suid taxon and that although its anistropy values increased through time, they remain well below those observed in modern Phacochoerus that specializes in fibrous, abrasive plants. Based on these results, in combination with comparative and experimental DMT, enamel carbon isotopic, and morphological data, Louail et al. (2024) propose that Omo Kolpochoerus preferred short, soft and low abrasive herbaceous plants (e.g., fresh grass shoots), probably in more mesic habitats. Louail et al. (2024) note that with the wide temporal and geographic distribution of Kolpochoerus, different species and populations may have had different feeding habits as they exploited different local habitats. However, it is noteworthy that similar inferences were made at other hominin sites based on other types of dietary data (e.g., Harris & Cerling, 2002; Rannikko et al., 2017, 2020; Yang et al., 2022). If this is an indication of their habitat preferences, the wide-ranging distribution of Kolpochoerus may suggest that mesic habitats with short, soft herbaceous plants were present in various proportions at most Plio-Pleistocene hominin sites. References Harris, J. M., and Cerling, T. E. (2002). Dietary adaptations of extant and Neogene African suids. Journal of Zoology, 256(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952836902000067 Harris, J. M., and White, T. D. (1979). Evolution of the Plio-Pleistocene African Suidae. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 69(2), 1–128. https://doi.org/10.2307/1006288 Heinzelin, J. de. (1983). The Omo Group. Archives of the International Omo Research Expedition. Volume 85. Annales du Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, série 8, Sciences géologiques, Tervuren, 388 p. Kidane, T., Brown, F. H., and Kidney, C. (2014). Magnetostratigraphy of the fossil-rich Shungura Formation, southwest Ethiopia. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 97, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2014.05.005 Louail, M., Souron, A., Merceron, G., and Boisserie, J.-R. (2024). New insights on feeding habits of Kolpochoerus from the Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) using dental microwear texture analysis. PaleorXiv, dbgtp, ver. 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/dbgtp McDougall, I., Brown, F. H., Vasconcelos, P. M., Cohen, B. E., Thiede, D. S., and Buchanan, M. J. (2012). New single crystal 40Ar/39Ar ages improve time scale for deposition of the Omo Group, Omo–Turkana Basin, East Africa. Journal of the Geological Society, 169(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1144/0016-76492010-188 Merceron, G., Escarguel, G., Angibault, J.-M., and Verheyden-Tixier, H. (2010). Can dental microwear textures record inter-individual dietary variations? PLoS ONE, 5(3), e9542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009542 Rannikko, J., Adhikari, H., Karme, A., Žliobaitė, I., and Fortelius, M. (2020). The case of the grass‐eating suids in the Plio‐Pleistocene Turkana Basin: 3D dental topography in relation to diet in extant and fossil pigs. Journal of Morphology, 281(3), 348–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.21103 Rannikko, J., Žliobaitė, I., and Fortelius, M. (2017). Relative abundances and palaeoecology of four suid genera in the Turkana Basin, Kenya, during the late Miocene to Pleistocene. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 487, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.08.033 Scott, R. S., Teaford, M. F., and Ungar, P. S. (2012). Dental microwear texture and anthropoid diets. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 147(4), 551–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22007 Scott, R. S., Ungar, P. S., Bergstrom, T. S., Brown, C. A., Childs, B. E., Teaford, M. F., and Walker, A. (2006). Dental microwear texture analysis: Technical considerations. Journal of Human Evolution, 51(4), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.006 Souron, A., Merceron, G., Blondel, C., Brunetière, N., Colyn, M., Hofman-Kamińska, E., and Boisserie, J.-R. (2015). Three-dimensional dental microwear texture analysis and diet in extant Suidae (Mammalia: Cetartiodactyla). Mammalia, 79(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/mammalia-2014-0023 Ungar, P. S., Abella, E. F., Burgman, J. H. E., Lazagabaster, I. A., Scott, J. R., Delezene, L. K., Manthi, F. K., Plavcan, J. M., and Ward, C. V. (2020). Dental microwear and Pliocene paleocommunity ecology of bovids, primates, rodents, and suids at Kanapoi. Journal of Human Evolution, 140, 102315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.03.005 Yang, D., Pisano, A., Kolasa, J., Jashashvili, T., Kibii, J., Gomez Cano, A. R., Viriot, L., Grine, F. E., and Souron, A. (2022). Why the long teeth? Morphometric analysis suggests different selective pressures on functional occlusal traits in Plio-Pleistocene African suids. Paleobiology, 48(4), 655–676. https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2022.11 | New insights on feeding habits of *Kolpochoerus* from the Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) using dental microwear texture analysis | Margot Louail, Antoine Souron, Gildas Merceron, Jean-Renaud Boisserie | <p>During the Neogene and the Quaternary, African suids show dental morphological changes considered to reflect adaptations to increasing specialization on graminivorous diets, notably in the genus <em>Kolpochoerus</em>. They tend to exhibit elong... |  | Paleoecology, Vertebrate paleontology | Denise Su | 2023-08-28 10:38:33 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jérémy Anquetin

Faysal Bibi

Guillaume Billet

Andrew A. Farke

Franck Guy

Leslea J. Hlusko

Melanie Hopkins

Cynthia V. Looy

Jesús Marugán-Lobón

Ilaria Mazzini

P. David Polly

Caroline A.E. Strömberg