Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * ▲ | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Oct 2023

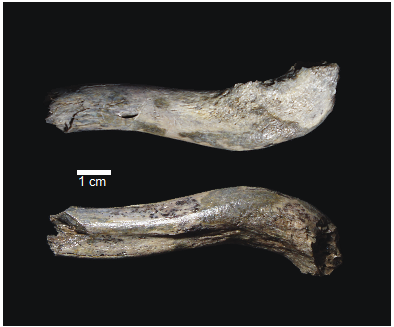

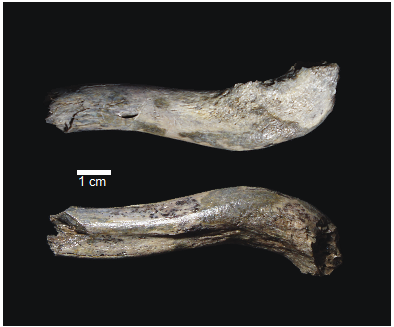

OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai GorgeCatherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656A new method for measuring clavicular curvatureRecommended by Nuria Garcia based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of the hominid clavicle has not been studied in depth by paleoanthropologists given its high morphological variability and the scarcity of complete diagnosable specimens. A nearly complete Nacholapithecus clavicle from Kenya (Senut et al. 2004) together with a fragment from Ardipithecus from the Afar region of Ethiopia (Lovejoy et al. 2009) complete our knowledge of the Miocene record. The Australopithecus collection of clavicles from Eastern and South African Plio-Pleistocene sites is slightly more abundant but mostly represented by fragmentary specimens. The number of fossil clavicles increases for the genus Homo from more recent sites and thus our potential knowledge about the shoulder evolution. In their new contribution, Taylor et al. (2023) present a detailed analysis of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominin clavicle recovered from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). The work goes over previous studies which included clavicles found in the hominid fossil record. The text is accompanied by useful tables of data and a series of excellent photographs. It is a great opportunity to learn its role in the evolution of the hominid shoulder gird as clavicles are relatively poorly preserved in the fossil record compared to other long bones. The study compares the specimen OH 89 with five other hominid clavicles and a sample of 25 modern clavicles, 30 Gorilla, 31 Pan and 7 Papio. The authors propose a new methodology for measuring clavicular curvature using measurements of sternal and acromial curvature, from which an overall curvature measurement is calculated. The study of OH 89 provides good evidence about the hominid who lived 1.8 million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge region. This time period is especially relevant because it can help to understand the morphological changes that occurred between Australopithecus and the appearance of Homo. The authors conclude that OH 89 is the largest of the hominid clavicles included in the analysis. Although they are not able to assign this partial element to species level, this clavicle from Olduvai is at the larger end of the variation observed in Homo sapiens and show similarities to modern humans, especially when analysing the estimated sinusoidal curvature. References Lovejoy, C. O., Suwa, G., Simpson, S. W., Matternes, J. H., and White, T. D. (2009). The Great Divides: Ardipithecus ramidus peveals the postcrania of our last common ancestors with African apes. Science, 326(5949), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1175833 Senut, B., Nakatsukasa, M., Kunimatsu, Y., Nakano, Y., Takano, T., Tsujikawa, H., Shimizu, D., Kagaya, M., and Ishida, H. (2004). Preliminary analysis of Nacholapithecus scapula and clavicle from Nachola, Kenya. Primates, 45(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-003-0073-5 Taylor, C., Masao, F., Njau, J. K., Songita, A. V., and Hlusko, L. J. (2023). OH 89: A newly described ∼1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge. bioRxiv, 526656, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656 | OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge | Catherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko | <p>Objectives: Here, we describe the morphology and geologic context of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. We compare the morphology and clavicular curvature of OH 89 to modern humans, extant apes... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Methods, Morphological evolution, Paleoanthropology, Vertebrate paleontology | Nuria Garcia | 2023-02-08 19:45:01 | View | |

04 Jun 2024

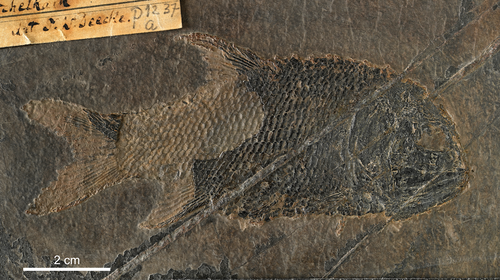

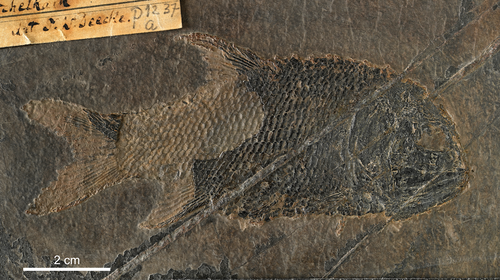

New generic name for a small Triassic ray-finned fish from Perledo (Italy)Adriana López-Arbarello, Rainer Brocke https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/bxmg5A new study on the halecomorph fishes from the Triassic of Perledo (Italy) highlights important issues in PalaeoichthyologyRecommended by Hugo Martín Abad based on reviews by Guang-Hui Xu and 1 anonymous reviewerMesozoic fishes are extremely diverse. In fact, fishes are the most diverse group of vertebrates during the Mesozoic─just as during any other era. Yet, their study is severely underrepresented in comparison to other fossil groups. There are just too few palaeoichthyologists to deal with such a vast diversity of fishes. Nonetheless, thanks to the huge efforts they have made over the last few decades, we have come a long way in our understanding of Mesozoic ichthyofaunas. One of such devoted palaeoichthyologists is Dr. Adriana López-Arbarello, whose contributions have been crucial in elucidating the phylogenetic interrelationships and taxonomic diversity of Mesozoic actinopterygian fishes (e.g., López-Arbarello, 2012; López-Arbarello & Sferco, 2018; López-Arbarello & Ebert, 2023). In her most recent manuscript, Dr. López-Arbarello has joined forces with Dr. Rainer Brocke to tackle the taxonomy and systematics of the halecomorph fishes from one of the most relevant Triassic sites, the upper Ladinian Perledo locality from Italy (López-Arbarello & Brocke, 2024). Fossil fishes were reported for the first time from Perledo in the first half of the 19th century (Balsamo-Crivelli, 1839), and up to 30 different species were described from the locality in the subsequent decades. Unfortunately, this is one of the multiple examples of fossil collections that suffered the effects of World War II, and most of the type material was lost. As a consequence, many of those 30 species that have been described over the years are in need of a revision. Based on the study of additional material that was transferred to Germany and is housed at the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum, López-Arbarello & Brocke (2024) confirm the presence of four different species of halecomorph fishes in Perledo, which were previously put under synonymy (Lombardo, 2001). They provide new detailed information on the anatomy of two of those species, together with their respective diagnoses. But more importantly, they carry out a thorough exercise of taxonomy, rigorously applying the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature to disentangle the intricacies in the taxonomic story of the species placed in the genus Allolepidotus. As a result, they propose the presence of the species A. ruppelii, which they propose to be the type species for that genus (instead of A. bellottii, which they transfer to the genus Eoeugnathus). They also propose a new genus for the other species originally included in Allolepidotus, A. nothosomoides. Finally, they provide a set of measurements and ratios for Pholidophorus oblongus and Pholidophorus curionii, the other two species previously put in synonymy with A. bellottii, to demonstrate their validity as different species. However, due to the loss of the type material, the authors propose that these two species remain as nomina dubia. In summary, apart from providing new detailed anatomical descriptions of two species and solving some long-standing issues with the taxonomy of the halecomorphs from the relevant Triassic Perledo locality, the paper by López-Arbarello & Rainer (2024) highlights three important topics for the study of the fossil record: 1) we should never forget that world-scale problems, such as World Wars, also affect our capacity to understand the natural world in which we live, and the whole society should be aware if this; 2) the importance of exhaustively following the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature when describing new species; and 3) we are in need of new palaeoichthyologists to, in Dr. López-Arbarello’s own words, “unveil the mysteries of those marvellous Mesozoic ichthyofaunas.” References Balsamo-Crivelli, G. (1839). Descrizione di un nuovo rettile fossile, della famiglia dei Paleosauri, e di due pesci fossili, trovati nel calcare nero, sopra Varenna sul lago di Como, dal nobile sig. Ludovico Trotti, con alcune riflessioni geologiche. Il politecnico repertorio mensile di studj applicati alla prosperita e coltura sociale, 1, 421–431. Lombardo, C. (2001). Actinopterygians from the Middle Triassic of northern Italy and Canton Ticino (Switzerland): Anatomical descriptions and nomenclatural problems. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 107, 345–369. https://doi.org/10.13130/2039-4942/5439 López-Arbarello, A. (2012). Phylogenetic interrelationships of ginglymodian fishes (Actinopterygii: Neopterygii). PLOS ONE, 7(7), e39370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039370 López-Arbarello, A., and Brocke, R. (2024). New generic name for a small Triassic ray-finned fish from Perledo (Italy). PaleorXiv, bxmg5, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/bxmg5 López-Arbarello, A., and Ebert, M. (2023). Taxonomic status of the caturid genera (Halecomorphi, Caturidae) and their Late Jurassic species. Royal Society Open Science, 10(1), 221318. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.221318 López-Arbarello, A., and Sferco, E. (2018). Neopterygian phylogeny: The merger assay. Royal Society Open Science, 5(3), 172337. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.172337 | New generic name for a small Triassic ray-finned fish from Perledo (Italy) | Adriana López-Arbarello, Rainer Brocke | <p>Our new study of the species originally included in the genus <em>Allolepidotus</em> led to the taxonomic revision of the halecomorph species from the Triassic of Perledo, Italy. The morphological variation revealed by the analysis of the type ... |  | Fossil record, Systematics, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology | Hugo Martín Abad | 2024-03-21 11:53:53 | View | |

20 Oct 2020

Evidence of high Sr/Ca in a Middle Jurassic murolith coccolith speciesBaptiste Suchéras-Marx, Fabienne Giraud, Alexandre Simionovici, Rémi Tucoulou, Isabelle Daniel https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/dcfuqNew results and challenges in Sr/Ca studies on Jurassic coccolithophoridsRecommended by Antonino Briguglio based on reviews by Kenneth De Baets and 1 anonymous reviewerThis interesting publication by Suchéras-Marx et al. (2020) highlights peculiar aspects of geochemistry in nannofossils, specifically coccolithophorids. One of the main application of geochemistry on fossil shells is to get hints on the physiology of such extinct taxa. Here, the authors try to get information on the calcification mechanism and processes in Jurassic coccoliths. Coccoliths build a test made of calcium carbonate and one of the most common geochemical proxies used for this fossil group is the Sr/Ca ratio. This isotopic ratio has good chances to be successfully used as a robust proxy for paleoenvironmental reconstruction, but, concerning Jurassic coccoliths things seem to be not straightforward. The authors managed to compare the isotopic value of Sr/Ca measured on Jurassic coccoliths from different taxonomic groups: the murolith Crepidolithus crassus and the placoliths Watznaueria contracta and Discorhabdus striatus. The results they got clearly show that the Sr/Ca ratio cannot be used as a universal proxy because these species exhibit very different values despite coming from the same stratigraphic level and having undergone minimal diagenetic modification. Data seem to point to a Sr/Ca ratio up to 10 times higher in the murolith species than in the placolith taxa (Suchéras-Marx et al., 2020). One of the explanation given here takes advantage of modern coccolith data and hints to specific polysaccharides that would control the growth of the long R unit in the murolith species. As always, there is plenty of space for additional research, possibly on modern taxa, to sort out the scientific questions that arise from this work. References Suchéras-Marx, B., Giraud, F., Simionovici, A., Tucoulou, R., & Daniel, I. (2020). Evidence of high Sr/Ca in a Middle Jurassic murolith coccolith species. PaleorXiv, dcfuq, version 7, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/dcfuq | Evidence of high Sr/Ca in a Middle Jurassic murolith coccolith species | Baptiste Suchéras-Marx, Fabienne Giraud, Alexandre Simionovici, Rémi Tucoulou, Isabelle Daniel | <p>Paleoceanographical reconstructions are often based on microfossil geochemical analyses. Coccoliths are the most ancient, abundant and continuous record of pelagic photic zone calcite producer organisms. Hence, they could be valuable substrates... |  | Microfossils, Micropaleontology, Nanofossils | Antonino Briguglio | 2020-05-18 16:11:35 | View | |

03 Jul 2024

Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successionsNiklas Hohmann, Joel R. Koelewijn, Peter Burgess, Emilia Jarochowska https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.18.572098Advances in understanding how stratigraphic structure impacts inferences of phenotypic evolutionRecommended by Melanie Hopkins based on reviews by Bjarte Hannisdal, Katharine Loughney, Gene Hunt and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bjarte Hannisdal, Katharine Loughney, Gene Hunt and 1 anonymous reviewer

A fundamental question in evolutionary biology and paleobiology is how quickly populations and/or species evolve and under what circumstances. Because the fossil record affords us the most direct view of how species lineages have changed in the past, considerable effort has gone into developing methodological approaches for assessing rates of evolution as well as what has been termed “mode of evolution” which generally describes pattern of evolution, for example whether the morphological change captured in fossil time series are best characterized as static, punctuated, or trending (e.g., Sheets and Mitchell, 2001; Hunt, 2006, 2008; Voje et al., 2018). The rock record from which these samples are taken, however, is incomplete, due to spatially and temporally heterogenous sediment deposition and erosion. The resulting structure of the stratigraphic record may confound the direct application of evolutionary models to fossil time series, most of which come from single localities. This pressing issue is tackled in a new study entitled “Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions” (Hohmann et al., 2024). The “carbonate successions” part of the title is important. Previous similar work (Hannisdal, 2006) used models for siliciclastic depositional systems to simulate the rock record. Here, the authors simulate sediment deposition across a carbonate platform, a system that has been treated as fundamentally different from siliciclastic settings, from both the point of view of geology (see Wagoner et al., 1990; Schlager, 2005) and ecology (Hopkins et al., 2014). The authors do find that stratigraphic structure impacts the identification of mode of evolution but not necessarily in the way one might expect; specifically, it is less important how much time is represented compared to the size and distribution of gaps, regardless of where you are sampling along the platform. This result provides an important guiding principle for selecting fossil time series for future investigations. Another very useful result of this study is the impact of time series length, which in this case should be understood as the density of sampling over a particular time interval. Counterintuitively, the probability of selecting the data-generating model as the best model decreases with increased length. The authors propose several explanations for this, all of which should inspire further work. There are also many other variables that could be explored in the simulations of the carbonate models as well as the fossil time series. For example, the authors chose to minimize within-sample variation in order to avoid conflating variability with evolutionary trends. But greater variance also potentially impacts model selection results and underlies questions about how variation relates to evolvability and the potential for directional change. Lastly, readers of Hohmann et al. (2024) are encouraged to also peruse the reviews and author replies associated with the PCI Paleo peer review process. The discussion contained in these documents touch on several important topics, including model performance and model selection, the nature of nested model systems, and the potential of the forwarding modeling approach. References Hannisdal, B. (2006). Phenotypic evolution in the fossil record: Numerical experiments. The Journal of Geology, 114(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1086/499569 Hohmann, N., Koelewijn, J. R., Burgess, P., and Jarochowska, E. (2024). Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions. bioRxiv, 572098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.18.572098 Hopkins, M. J., Simpson, C., and Kiessling, W. (2014). Differential niche dynamics among major marine invertebrate clades. Ecology Letters, 17(3), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12232 Hunt, G. (2006). Fitting and comparing models of phyletic evolution: Random walks and beyond. Paleobiology, 32(4), 578–601. https://doi.org/10.1666/05070.1 Hunt, G. (2008). Gradual or pulsed evolution: When should punctuational explanations be preferred? Paleobiology, 34(3), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1666/07073.1 Schlager, W. (Ed.). (2005). Carbonate Sedimentology and Sequence Stratigraphy. SEPM Concepts in Sedimentology and Paleontology No. 8. https://doi.org/10.2110/csp.05.08 Sheets, H. D., and Mitchell, C. E. (2001). Why the null matters: Statistical tests, random walks and evolution. Genetica, 112, 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013308409951 Voje, K. L., Starrfelt, J., and Liow, L. H. (2018). Model adequacy and microevolutionary explanations for stasis in the fossil record. The American Naturalist, 191(4), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/696265 Wagoner, J. C. V., Mitchum, R. M., Campion, K. M., and Rahmanian, V. D. (1990). Siliciclastic Sequence Stratigraphy in Well Logs, Cores, and Outcrops: Concepts for High-Resolution Correlation of Time and Facies. AAPG Methods in Exploration Series No. 7. https://doi.org/10.1306/Mth7510 | Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions | Niklas Hohmann, Joel R. Koelewijn, Peter Burgess, Emilia Jarochowska | <p><strong>Background:</strong> The fossil record provides the unique opportunity to observe evolution over millions of years, but is known to be incomplete. While incompleteness varies spatially and is hard to estimate for empirical sections, com... | Evolutionary biology, Evolutionary patterns and dynamics, Fossil record, Methods, Sedimentology | Melanie Hopkins | 2023-12-19 08:10:00 | View | ||

19 Aug 2021

Through a glass darkly, but with more understanding of arthropod originRecommended by Tae-Yoon Park based on reviews by Gerhard Scholtz and Jean VannierArthropods constitute 85% of all described animal species on Earth (Brusca et al., 2016), being the most successful animal phylum at present. This phylum did not even have a shabby beginning. The fossil record shows that they were dominating the sea even in the early Cambrian (Caron and Jackson, 2008; Zhao et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2019). This planet is and has been indeed dominated by arthropods. Within the context of the Big Bang of animal evolution known as the Cambrian Explosion, delving into the origin of arthropods has been one of the all-time fascinating research themes in paleontology, and discussions on the ‘origin’ and ‘early evolution’ of arthropods from the paleontological perspective have not been infrequent (e.g., Budd and Telford, 2009; Edgecombe and Legg, 2014; Daley et al., 2018; Edgecombe, 2020). In this context, Aria (2021) provides an interesting integration of his view on arthropod origin and early evolution. Based on well-preserved Burgess Shale materials, together with other impressive researches mainly with Jean-Bernard Caron (e.g., Aria and Caron, 2015; Caron and Aria, 2017), Cédric Aria made his name known with papers searching for the stem-groups of the two major euarthropod lineages, the Mandibulata and the Chelicerata (Aria and Caron, 2017, 2019), for which (and for his subsequent researches) assembling a large dataset for arthropod phylogeny was inevitable. Subsequently, there have been several major discoveries which could improve our understanding on early arthropod evolution (e.g., Lev and Chipman, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). For Cédric Aria, therefore, this timely presentation of his own perspective on the origin of early evolution of arthropods may have been preordain. This review stands out because it discusses almost all aspects of arthropod origin and early evolution that can be possibly covered by paleontology (many, if not all, of which are still controversial). Some of his views may be considered a brave attempt. For instance, based on the widespread occurrences of suspension feeders, Aria (2021) proposes the early Cambrian “planktonic revolution,” which has been associated rather with the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (Servais et al., 2016). Given the presence of lophotrochozoans and echinoderms in which the presence of planktonic larvae was likely to have been one of the most inclusive features, the “early Cambrian planktonic revolution” might be plausible, but I wonder if including arthropods into the “earlier revolution” can be readily acceptable. Arthropods arose from direct-developing ancestors, and crustaceans (the main group with planktonic larvae) are pretty much derived in the arthropod phylogenetic tree. Trilobites, inarguably the best-studied Cambrian arthropods, for example, began with direct-developing benthic protaspides in the early Cambrian and Miaolingian. The first hint of planktonic protaspides appeared in the Furongian, and it was not until the Tremadocian when such indirect developing protaspides began to be widespread (Park and Kihm, 2015), which complies well with the onset of the ‘Ordovician Planktonic Revolution’ in the Furongian, as suggested by Servais et al. (2016). But in general, this review presents well-organized views worth hearing, and since many of the points are subject to debate, this review could be a friendly manual for those who have similar views, while it could form a fresh ground to attack for those who have disparate views. One of the endless debates in arthropod research comes from the arthropod head problem (Budd, 2002), which centers on the homology of frontal-most appendages in radiodonts, megacheirans, chelicerates, and mandibulates, as well as on the hypostome-labrum complex. Based on recent interesting discoveries of early arthropods from the Chengjiang biota (Aria, 2020; Zeng et al., 2020), Aria (2021) pertinently coined a term ‘cheirae’ for the frontalmost prehensile appendages of radiodonts and megacheirans, implying homology of them. I assume that not all researchers would agree with this though, as well as with his model of hypostome/labrum complex evolution. Notorious disaccords have also occurred around the phylogenetic positions of early arthropods, such as isoxyids, megacheirans, fuxianhuiids, and artiopodans; different research groups have invariably come up with different topologies. Cédric Aria has presented his own topologies (Aria, 2019, 2020), and figure 2 of Aria (2021) summarizes his perspective very well in combination with major character evolutions. What makes this review especially interesting is a courageous discussion about the origin of biramous appendage, a subject that has been only briefly discussed or overlooked in recent literature. In the current mainstream of this debate lies the concept of ‘gilled lobopodians’ (Budd, 1998), which was complicated by the weird two separate rows of lateral flaps of Aegirocassis (Van Roy et al., 2015). Aria (2021) adds an interesting alternative scenario to this: biramicity originated from the split of main limb axis, as seen in the isoxyid Surusicaris (Aria and Caron, 2015). The figure 3d of his review, therefore, is worth giving thoughts for any arthropodologists who are interested in the origin of arthropod legs. It is true that our understanding of the origin and early evolution of arthropods is still in a mist. Nevertheless, we have recently seen advancements, such as those aided by new types of analysis (Liu et al., 2020), the discoveries of new early arthropods with unexpected morphologies (Aria et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020), and the groundbreaking Evo-Devo research (Lev and Chipman, 2020). We will keep jousting on various aspects of the origin and early evolution of arthropods, but for some aspects we are seemingly heading for the final, as implicitly alluded in Aria (2021).

References Aria C (2019). Reviewing the bases for a nomenclatural uniformization of the highest taxonomic levels in arthropods. Geological Magazine 156, 1463–1468. Aria C (2020). Macroevolutionary patterns of body plan canalization in euarthropods. Paleobiology 46, 569–593. doi: 10.1017/pab.2020.36 Aria C (2021). The origin and early evolution of arthropods. PaleorXiv, 4zmey, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/4zmey Aria C and Caron JB (2015). Cephalic and limb anatomy of a new isoxyid from the Burgess Shale and the role of "stem bivalved arthropods" in the disparity of the frontalmost appendage. PLOS ONE 10, e0124979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124979 Aria C and Caron JB (2017). Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan. Nature 545, 89–92. Aria C and Caron JB (2019). A middle Cambrian arthropod with chelicerae and proto-book gills. Nature 573, 586–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1525-4 Aria C, Zhao F, Zeng H, Guo J, and Zhu M (2020). Fossils from South China redefine the ancestral euarthropod body plan. BMC Evolutionary Biology 20, 4. Brusca RC, Moore W, and Shuster SM (2016). Invertebrates. Third edition. Sunderland, Massachusetts U.S.A: Sinauer Associates. isbn: 978-1-60535-375-3 Budd GE (1998). Stem-group arthropods from the Lower Cambrian Sirius Passet fauna of North Greenland. In: Arthropod Relationships. Ed. by Fortey RA and Thomas RH. London, UK: Chapman & Hall, pp. 125–138. Budd GE (2002). A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature 417, 271–275. doi: 10.1038/417271a Budd GE and Telford MJ (2009). The origin and evolution of arthropods. Nature 457, 812–817. doi: 10.1038/Nature07890 Caron JB and Aria C (2017). Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods. BMC Evolutionary Biology 17, 29. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y Caron JB and Jackson DA (2008). Paleoecology of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 258, 222–256. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.023 Daley AC, Antcliffe JB, Drage HB, and Pates S (2018). Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, 5323–5331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719962115 Edgecombe GD (2020). Arthropod origins: Integrating paleontological and molecular evidence. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51, 1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-124437 Edgecombe GD and Legg DA (2014). Origins and early evolution of arthropods. Palaeontology 57, 457–468. Fu D, Tong G, Dai T, Liu W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Cui L, Li L, Yun H, Wu Y, Sun A, Liu C, Pei W, Gaines RR, and Zhang X (2019). The Qingjiang biota—A Burgess Shale–type fossil Lagerstätte from the early Cambrian of South China. Science 363, 1338–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8800 Lev O and Chipman AD (2020). Development of the pre-gnathal segments of the insect head indicates they are not serial homologues of trunk segments. bioRxiv, 2020.09.16.299289. doi: 10.1101/2020.09.16.299289 Liu Y, Ortega-Hernández J, Zhai D, and Hou X (2020). A reduced labrum in a Cambrian great-appendage euarthropod. Current Biology 30, 3057–3061.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.085 Park TYS and Kihm JH (2015). Post-embryonic development of the Early Ordovician (ca. 480 Ma) trilobite Apatokephalus latilimbatus Peng, 1990 and the evolution of metamorphosis. Evolution & Development 17, 289–301. doi: 10.1111/ede.12138 Servais T, Perrier V, Danelian T, Klug C, Martin R, Munnecke A, Nowak H, Nützel A, Vandenbroucke TR, Williams M, and Rasmussen CM (2016). The onset of the ‘Ordovician Plankton Revolution’ in the late Cambrian. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 458, 12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.11.003 Van Roy P, Daley AC, and Briggs DEG (2015). Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. Nature 522, 77–80. doi: 10.1038/nature14256 Zeng H, Zhao F, Niu K, Zhu M, and Huang D (2020). An early Cambrian euarthropod with radiodont-like raptorial appendages. Nature 588, 101–105. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7 Zhao F, Caron JB, Bottjer DJ, Hu S, Yin Z, and Zhu M (2014). Diversity and species abundance patterns of the Early Cambrian (Series 2, Stage 3) Chengjiang Biota from China. Paleobiology 40, 50–69. doi: 10.1666/12056 | The origin and early evolution of arthropods | Cédric Aria | <p style="text-align: justify;">The rise of arthropods is a decisive event in the history of life. Likely the first animals to have established themselves on land and in the air, arthropods have pervaded nearly all ecosystems and have become pilla... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Invertebrate paleontology, Macroevolution, Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Taphonomy, Taxonomy | Tae-Yoon Park | 2021-04-26 13:51:21 | View | |

13 Jul 2023

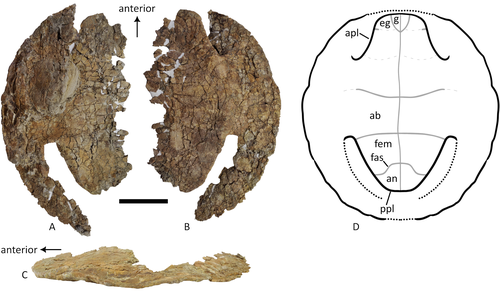

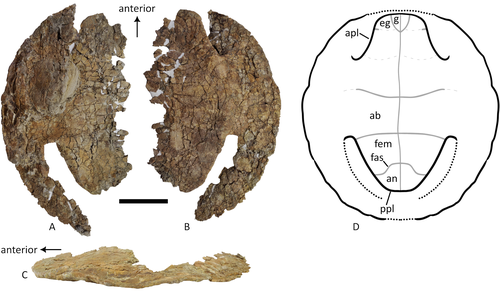

A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USAKa Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3acNew baenid turtle material from the Campanian of WyomingRecommended by Jérémy Anquetin based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Brent Adrian

The Baenidae form a diverse extinct clade of exclusively North American paracryptodiran turtles known from the Early Cretaceous to the Eocene (Hay, 1908; Gaffney, 1972; Joyce and Lyson, 2015). Their fossil record was recently extended down to the Berriasian-Valanginian (Joyce et al. 2020), but the group probably originates in the Late Jurassic because it is usually retrieved as the sister group of Pleurosternidae in phylogenetic analyses. However, baenids only became abundant during the Late Cretaceous, when they are restricted in distribution to the western United States, Alberta and Saskatchewan (Joyce and Lyson, 2015). During the Campanian, baenids are abundant in the northern (Alberta, Montana) and southern (Texas, New Mexico, Utah) parts of their range, but in the middle part of this range they are mostly represented by poorly diagnosable shell fragments. In their new contribution, Wu et al. (2023) describe a new articulated baenid specimen from the Campanian Mesaverde Formation of Wyoming. Despite its poor preservation, they are able to confidently assign this partial shell to Neurankylus sp., hence definitively confirming the presence of baenids and Neurankylus in this formation. Incidentally, this new specimen was found in a non-fluvial depositional environment, which would also confirm the interpretation of Neurankylus as a pond turtle (Hutchinson and Archibald, 1986; Sullivan et al., 1988; Wu et al., 2023; see also comments from the second reviewer). The study of Wu et al. (2023) also includes a detailed account of the state of the fossil when it was discovered and the subsequent extraction and preparation procedures followed by the team. This may seem excessive or out of place to some, but I agree with the authors that such information, when available, should be more commonly integrated into scientific articles describing new fossil specimens. Preparation and restoration can have a significant impact on the perceived morphology. This must be taken into account when working with fossil specimens. The chemicals or products used to treat, prepare, or consolidate the specimens are also important information for long-term curation. Therefore, it is important that such information is recorded and made available for researchers, curators, and preparators. References Gaffney, E. S. (1972). The systematics of the North American family Baenidae (Reptilia, Cryptodira). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 147(5), 241–320. Hay, O. P. (1908). The Fossil Turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.12500 Hutchison, J. H., and Archibald, J. D. (1986). Diversity of turtles across the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary in Northeastern Montana. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(86)90133-1 Joyce, W. G., and Lyson, T. R. (2015). A review of the fossil record of turtles of the clade Baenidae. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 56(2), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.3374/014.058.0105 Joyce, W. G., Rollot, Y., and Cifelli, R. L. (2020). A new species of baenid turtle from the Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation of South Dakota. Fossil Record, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5194/fr-23-1-2020 Sullivan, R. M., Lucas, S. G., Hunt, A. P., and Fritts, T. H. (1988). Color pattern on the selmacryptodiran turtle Neurankylus from the Early Paleocene (Puercan) of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Contributions in Science, 401, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.241286 Wu, K. Y., Heuck, J., Varriale, F. J., and Farke, A. (2023). A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA. PaleorXiv, uk3ac, ver. 5, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/uk3ac | A baenid turtle shell from the Mesaverde Formation (Campanian, Late Cretaceous) of Park County, Wyoming, USA | Ka Yan Wu, Jared Heuck, Frank J. Varriale, and Andrew A. Farke | <p>The Mesaverde Formation of the Wind River and Bighorn basins of Wyoming preserves a rich yet relatively unstudied terrestrial and marine faunal assemblage dating to the Campanian. To date, turtles within the formation have been represented prim... |  | Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiogeography, Vertebrate paleontology | Jérémy Anquetin | 2023-01-16 16:26:43 | View | |

23 Apr 2021

The record of Deinotheriidae from the Miocene of the Swiss Jura Mountains (Jura Canton, Switzerland)Fanny Gagliardi, Olivier Maridet, Damien Becker https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.10.244061The fossil record of deinotheres in the Jura Mountains and the specific diversity of European deinotheriidsRecommended by Lionel Hautier based on reviews by Martin Pickford and 1 anonymous reviewerProboscideans belong to the Afrotheria, a superorder of mammals with an African origin, which was recently recognized based on molecular data (see review in Asher et al., 2009). The fossil record of Proboscidea is well documented and shows that an important part of their evolutionary history took place in Africa, with their representatives inhabiting the continent for at least 60 million years (Gheerbrant, 2009). However, proboscideans also proved to be great travellers, and a flourishing diversity of proboscidean forms colonized most of the continents of the planet, including Europe, from where they have since completely disappeared. Nowadays, Loxodonta africana, L. cyclotis, and Elephas maximus are flagship species of the African and Asian faunas, but they only represent a minor part of the modern mammalian diversity. In contrast, their ancient relatives seemed to be relatively abundant in past ecosystems (Sanders et al., 2010), which raised a number of interesting, but challenging, questions relative to the structure and evolution of ancient megaherbivore communities (Calandra et al., 2008). Among proboscideans, deinotheres represent a special case. Their morphology clearly departs from that of other groups, notably in displaying distinctive downward curving lower tusks. Compared to their successful sister group the elephantiforms (i.e., all elephant-like proboscideans closely related to modern elephants; sensu Tassy, 1994), deinotheriids are often regarded as the poor sibling of the Proboscidea for showing a relatively low specific diversity and displaying a reduced morphological variability. In fact, many grey areas still exist regarding the evolution of this unique family. In their article, Gagliardi et al. (2021) revised the material of deinotheres recovered in the Miocene sands of the Swiss Jura Mountains. They described for the first time the material attributed to Prodeinotherium bavaricum and Deinotherium giganteum from the Delémont valley, and reported the presence of a third species, Deinotherium levius, from the locality of Charmoille in Ajoie. Based on comparisons made on specimens recovered from middle to the late Miocene localities, the authors discussed the potential link between the mode and tempo of deinothere dispersions and the evolution environmental and climatic conditions in Western and Eastern Europe during the Miocene. They also considered the evolution of ecological specializations in the group, especially with regard to size increase. Gagliardi et al. (2021) proposed to follow the two genera/five species concept (i.e., P. cuvieri, P. bavaricum, D. levius, D. giganteum, and D. proavum), which implies the co-existence of several deinothere species in Europe. The latter hypothesis contrasts with the recognition of a single African Deinotherium species (i.e., D. bozasi) in deposits dated from the late Miocene to the early Pleistocene (Sanders et al., 2010). Such a co-existence of European species was and still is debated; it was here questioned by both reviewers. However, as acknowledged by the authors, only an extensive revision of the material of all recognized species, in Europe and worldwide, will enable to shed more light on the deinothere morphological variability and specific diversity. There is no doubt that such a revision would have a profound impact on our view of the evolution of this enigmatic group.

References Asher, R. J., Bennett, N., & Lehmann, T. (2009). The new framework for understanding placental mammal evolution. BioEssays, 31(8), 853–864. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900053 Calandra, I., Göhlich, U. B., & Merceron, G. (2008). How could sympatric megaherbivores coexist? Example of niche partitioning within a proboscidean community from the Miocene of Europe. Naturwissenschaften, 95(9), 831–838. doi: 10.1007/s00114-008-0391-y Gagliardi, F., Maridet, O., & Becker, D. (2021). The record of Deinotheriidae from the Miocene of the Swiss Jura Mountains (Jura Canton, Switzerland). BioRxiv, 244061, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.1101/2020.08.10.244061 Gheerbrant, E. (2009). Paleocene emergence of elephant relatives and the rapid radiation of African ungulates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10717–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900251106 Sanders, W. J., Gheerbrant, E., Harris, J. M., Saegusa, H., & Delmer, C. (2010). Proboscidea. In L. Werdelin & W. J. Sanders (Eds.), Cenozoic Mammals of Africa (pp. 161–251). Berkeley: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/california/9780520257214.003.0015 Tassy, P. (1994). Origin and differentiation of the Elephantiformes (Mammalia, Proboscidea). Verhandlungen Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg, 34, 73–94. | The record of Deinotheriidae from the Miocene of the Swiss Jura Mountains (Jura Canton, Switzerland) | Fanny Gagliardi, Olivier Maridet, Damien Becker | <p>The Miocene sands of the Swiss Jura Mountains, long exploited in quarries for the construction industry, have yielded abundant fossil remains of large mammals. Among Deinotheriidae (Proboscidea), two species, Prodeinotherium bavaricum and Deino... |  | Fossil record, Paleobiogeography, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology | Lionel Hautier | 2020-08-11 10:17:38 | View | |

30 Oct 2019

The Morrison Formation Sauropod Consensus: A freely accessible online spreadsheet of collected sauropod specimens, their housing institutions, contents, references, localities, and other potentially useful informationEmanuel Tschopp, John A. Whitlock, D. Cary Woodruff, John R. Foster, Roberto Lei, Simone Giovanardi https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/ydvraSauropods under one (very high) roofRecommended by Jordan Mallon based on reviews by Kenneth Carpenter and Femke HolwerdaFossils get around. Any one fossil locality might be sampled by several collectors from as many institutions around the world. Alternatively, a single collector might heavily sample a site, and sell or trade parts of their collection to other institutions, scattering the fossils far and wide. These practices have the advantage of making fossils from any one locality available to researchers across the globe. However, they also have the disadvantage that, in order to systematically survey any one species, a researcher must follow innumerable trails of breadcrumb to get to where the relevant materials are held. This is true of many famous fossil localities, such as the Eocene Green River Formation in the USA, the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Morocco, or the Devonian Miguasha cliffs of Canada. It is especially true of the Upper Jurassic deposits of the Morrison Formation in the western USA, which have yielded an impressive assemblage of megaherbivorous sauropod dinosaurs over the last 150 years. Today, these bones are to be found in museums not just in the USA, but also in Canada, Argentina, Japan, Australia, Malaysia, South Africa, and throughout Europe. Trawling museum databases in search of sauropod material from the Morrison Formation can therefore be a daunting task, never mind traveling the globe to actually study them. A new paper by Tschopp et al. (2019) seeks to ease the burden on sauropod researchers by introducing a database of Morrison Formation sauropods, consisting of over 3000 specimens housed in nearly 40 institutions around the world. The authors are themselves sauropod workers and, having suffered first-hand the plight of studying material from the Morrison Formation, came up with a solution to the problem of keeping track of it all. The database is founded largely on material personally seen by the authors, supplemented by information from the literature and museum catalogs. The database further provides information on bone representation, ontogeny, locality details, and fine-scale stratigraphy, among other fields. Like any database, it is a living document that will continue to grow as new finds are made. Tschopp et al. (2019) have wisely chosen to allow others to contribute to the listing, but changes must first be vetted for accuracy. This product represents 10 years of work, and I have little doubt that it will be well-received by those of us who work on dinosaurs. Speaking personally, my PhD research on megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Canada led me to institutions in Canada, the USA, and the UK, and further stops to Spain and Argentina would have been beneficial, if affordable. Planning for this work would have been greatly assisted by a database like the one provided us by Tschopp et al. (2019). Many a future graduate student will undoubtedly owe them a debt of gratitude. References Tschopp, E., Whitlock, J. A., Woodruff, D. C., Foster, J. R., Lei, R., & Giovanardi, S. (2019). The Morrison Formation Sauropod Consensus: A freely accessible online spreadsheet of collected sauropod specimens, their housing institutions, contents, references, localities, and other potentially useful information. PaleorXiv, version 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/ydvra | The Morrison Formation Sauropod Consensus: A freely accessible online spreadsheet of collected sauropod specimens, their housing institutions, contents, references, localities, and other potentially useful information | Emanuel Tschopp, John A. Whitlock, D. Cary Woodruff, John R. Foster, Roberto Lei, Simone Giovanardi | <p>The Morrison Formation has been explored for dinosaurs for more than 150 years, in particular for large sauropod skeletons to be mounted in museum exhibits around the world. Several long-term campaigns to the Jurassic West of the United States ... |  | Fossil record, Methods, Paleobiodiversity, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology | Jordan Mallon | 2019-07-19 16:13:45 | View | |

16 Oct 2019

What do ossification sequences tell us about the origin of extant amphibians?Michel Laurin, Océane Lapauze, David Marjanović https://doi.org/10.1101/352609The origins of LissamphibiaRecommended by Robert Asher based on reviews by Jennifer Olori and 2 anonymous reviewersAmong living vertebrates, there is broad consensus that living tetrapods consist of amphibians and amniotes. Crown clade Lissamphibia contains frogs (Anura), salamanders (Urodela) and caecilians (Gymnophiona); Amniota contains Sauropsida (reptiles including birds) and Synapsida (mammals). Within Lissamphibia, most studies place frogs and salamanders in a clade together to the exclusion of caecilians (see Pyron & Wiens 2011). Among fossils, there are a number of amphibian and amphibian-like taxa generally placed in Temnospondyli and Lepospondyli. In contrast to the tree of living tetrapods, affinities of these fossils to some or all of the three extant lissamphibian groups have proven to be much harder to resolve. For example, temnospondyls might be stem tetrapods and lissamphibians a derived group of lepospondyls; alternatively, temnospondyls might be closer to the clade of frogs and salamanders, and lepospondyls to caecilians (compare Laurin et al. 2019: fig. 1d vs. 1f). Here, in order to assess which of these and other mutually exclusive topologies is optimal, Laurin et al. (2019) extract phylogenetic information from developmental sequences, in particular ossification. Several major differences in ossification are known to distinguish vertebrate clades. For example, due to their short intrauterine development and need to climb from the reproductive tract into the pouch, marsupial mammals famously accelerate ossification of their facial skeleton and forelimb; in contrast to placentals, newborn marsupials can climb, smell & suck before they have much in the way of lungs, kidneys, or hindlimbs (Smith 2001). Divergences among living and fossil amphibian groups are likely pre-Triassic (San Mauro 2010; Pyron 2011), much older than a Jurassic split between marsupials and placentals (Tarver et al. 2016), and the quality of the fossil record generally decreases with ever-older divergences. Nonetheless, there are a number of well-preserved examples of "amphibian"-grade tetrapods representing distinct ontogenetic stages (Schoch 2003, 2004; Schoch and Witzmann 2009; Olori 2013; Werneburg 2018; among others), all amenable to analysis of ossification sequences. Putting together a phylogenetic dataset based on ossification sequences is not trivial; sequences are not static features apparent on individual specimens. Rather, one needs multiple specimens representing discrete developmental stages for each taxon to be compared, meaning that sequences are usually available for only a few characters. Laurin et al. (2019) have nonetheless put together the most exhaustive matrix of tetrapod sequences so far, with taxon coverage ranging from 62 genera for appendicular characters to 107 for one of their cranial datasets, each sampling between 4-8 characters (Laurin et al. 2019: table 1). The small number of characters means that simply applying an optimality criterion (such as parsimony) is unlikely to resolve most nodes; treespace is too flat to be able to offer optimal peaks up which a search algorithm might climb. However, Laurin et al. (2019) were able to test each of the main competing hypotheses, defined a priori as a branching topology, given their ossification sequence dataset and a likelihood optimality criterion. Their most consistent result comes from their cranial ossification sequences and supports their "LH", or lepospondyl hypothesis (Laurin et al. 2019: fig. 1d). That is, relative to extinct, "amphibian"-grade taxa, Lissamphibia is monophyletic and nested within lepospondyls. Compared to mammals and birds (including dinosaurs), crown amphibian branches of the Tree of Life are exceptionally old. Each lissamphibian clade likely had diverged during Permian times (Marjanovic & Laurin 2008) and the crown group itself may even date to the Carboniferous (Pyron 2011). In contrast to mammoths and moas, no ancient DNA or collagen sequences are going to be available from >300 million-year-old fossils like the lepospondyl *Hyloplesion* (Olori 2013), although recently published methods for incorporating genomic signal from extant taxa (Beck & Baillie 2018; Asher et al. 2019) into studies of fossils could also be applied to these ancient divergences among amphibian-grade tetrapods. Ossification sequences represent another important, additional source of data with which to test the conclusion of Laurin et al. (2019) that monophyletic Lissamphibians shared a common ancestor with lepospondyls, among other hypotheses. **References** Asher, R. J., Smith, M. R., Rankin, A., & Emry, R. J. (2019). Congruence, fossils and the evolutionary tree of rodents and lagomorphs. Royal Society Open Science, 6(7), 190387. doi: [ 10.1098/rsos.190387 ](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rsos.190387 ) Beck, R. M. D., & Baillie, C. (2018). Improvements in the fossil record may largely resolve current conflicts between morphological and molecular estimates of mammal phylogeny. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1893), 20181632. doi: [ 10.1098/rspb.2018.1632](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rspb.2018.1632) Laurin, M., Lapauze, O., & Marjanović, D. (2019). What do ossification sequences tell us about the origin of extant amphibians? BioRxiv, 352609, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: [ 10.1101/352609](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/352609) Marjanović, D., & Laurin, M. (2008). Assessing confidence intervals for stratigraphic ranges of higher taxa: the case of Lissamphibia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 53(3), 413–432. doi: [ 10.4202/app.2008.0305](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.4202/app.2008.0305) Olori, J. C. (2013). Ontogenetic sequence reconstruction and sequence polymorphism in extinct taxa: an example using early tetrapods (Tetrapoda: Lepospondyli). Paleobiology, 39(3), 400–428. doi: [ 10.1666/12031](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1666/12031) Pyron, R. A. (2011). Divergence time estimation using fossils as terminal taxa and the origins of Lissamphibia. Systematic Biology, 60(4), 466–481. doi: [ 10.1093/sysbio/syr047](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/sysbio/syr047) Pyron, R. A., & Wiens, J. J. (2011). A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61(2), 543–583. doi: [ 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.012](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.012) San Mauro, D. (2010). A multilocus timescale for the origin of extant amphibians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 56(2), 554–561. doi: [ 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.019](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.019) Schoch, R. R. (2003). Early larval ontogeny of the Permo-Carboniferous temnospondyl *Sclerocephalus*. Palaeontology, 46(5), 1055–1072. doi: [ 10.1111/1475-4983.00333](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/1475-4983.00333) Schoch, R. R. (2004). Skeleton formation in the Branchiosauridae: a case study in comparing ontogenetic trajectories. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 24(2), 309–319. doi: [ 10.1671/1950](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1671/1950) Schoch, R. R., & Witzmann, F. (2009). Osteology and relationships of the temnospondyl genus *Sclerocephalus*. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 157(1), 135–168. doi: [ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00535.x](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00535.x) Smith, K. K. (2001). Heterochrony revisited: the evolution of developmental sequences. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 73(2), 169–186. doi: [ 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01355.x](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01355.x) Tarver, J. E., dos Reis, M., Mirarab, S., Moran, R. J., Parker, S., O’Reilly, J. E., & Pisani, D. (2016). The interrelationships of placental mammals and the limits of phylogenetic inference. Genome Biology and Evolution, 8(2), 330–344. doi: [ 10.1093/gbe/evv261](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/gbe/evv261) Werneburg, R. (2018). Earliest “nursery ground” of temnospondyl amphibians in the Permian. Semana, 32, 3–42. | What do ossification sequences tell us about the origin of extant amphibians? | Michel Laurin, Océane Lapauze, David Marjanović | <p>The origin of extant amphibians has been studied using several sources of data and methods, including phylogenetic analyses of morphological data, molecular dating, stratigraphic data, and integration of ossification sequence data, but a consen... |  | Evo-Devo, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Robert Asher | 2018-06-22 08:21:31 | View | |

22 Sep 2018

Palaeobiological inferences based on long bone epiphyseal and diaphyseal structure - the forelimb of xenarthrans (Mammalia)Eli Amson & John A. Nyakatura https://doi.org/10.1101/318121Inferences on the lifestyle of fossil xenarthrans based on limb long bone inner structureRecommended by Alexandra Houssaye based on reviews by Andrew Pitsillides and 1 anonymous reviewerBone inner structure bears a strong functional signal and can be used in paleontology to make inferences about the ecology of fossil forms. The increasing use of microtomography enables to analyze both cortical and trabecular features in three dimensions, and thus in long bones to investigate the diaphyseal and epiphyseal structures. Moreover, this can now be done through quantitative, and not only qualitative analyses. Studies focusing on the diaphyseal inner structure (cortical bone and sometimes also spongious bone) of long bones are rather numerous, but essentially based on 2D sections. It is only recently that analyses of the whole diaphyseal structure have been investigated. Studies on the trabecular architecture are much rarer. Amson & Nyakatura (2018) propose a comparative quantitative analysis combining parameters of the epiphyseal trabecular architecture and of the diaphyseal structure, using phylogenetically informed discriminant analyses, and with the aim of inferring the lifestyle of extinct taxa. The group of interest is xenarthrans, one of the four major extant clades of placental mammals. Xenarthrans exhibit different lifestyles, from fully terrestrial to arboreal, and show various degrees of fossoriality. The authors analyzed forelimb long bones of some fossil sloths and made comparisons with several species of extant xenarthrans. The aim was notably to discuss the degree of arboreality and fossoriality of these fossil forms. This study is among the first ones to conjointly analyze both diaphyseal and trabecular parameters to characterize lifestyles, and the first one outside of primates. No fossil form could undoubtedly be assigned to one lifestyle exhibited by extant xenarthrans, though some previous ecological hypotheses could be corroborated. This study also raised some technical challenges, linked to the sample and to the parameters studied, and thus constitutes a great step, from which to go further. References Amson, E., & Nyakatura, J. A. (2018). Palaeobiological inferences based on long bone epiphyseal and diaphyseal structure - the forelimb of xenarthrans (Mammalia). bioRxiv, 318121, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.1101/318121 | Palaeobiological inferences based on long bone epiphyseal and diaphyseal structure - the forelimb of xenarthrans (Mammalia) | Eli Amson & John A. Nyakatura | <p>Trabecular architecture (i.e., the main orientation of the bone trabeculae, their number, mean thickness, spacing, etc.) has been shown experimentally to adapt with great accuracy and sensitivity to the loadings applied to the bone during life.... |  | Biomechanics & Functional morphology, Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Histology, Methods, Morphological evolution, Paleobiology, Vertebrate paleontology | Alexandra Houssaye | 2018-05-14 08:35:20 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jérémy Anquetin

Faysal Bibi

Guillaume Billet

Andrew A. Farke

Franck Guy

Leslea J. Hlusko

Melanie Hopkins

Cynthia V. Looy

Jesús Marugán-Lobón

Ilaria Mazzini

P. David Polly

Caroline A.E. Strömberg