Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Feb 2025

A new tuna specimen (Genus Auxis) from the Duho Formation (Miocene) of South KoreaDayun Suh, Su-Hwan Kim, Gi-Soo Nam https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.29.605724Rare Miocene tuna fossil unearthed in South KoreaRecommended by Adriana López-Arbarello based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

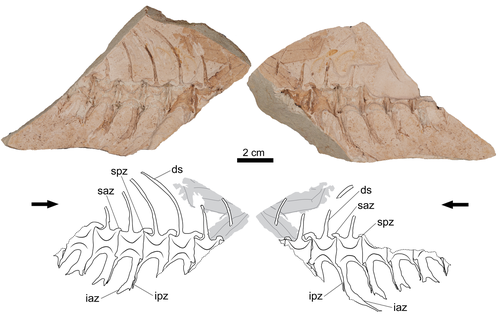

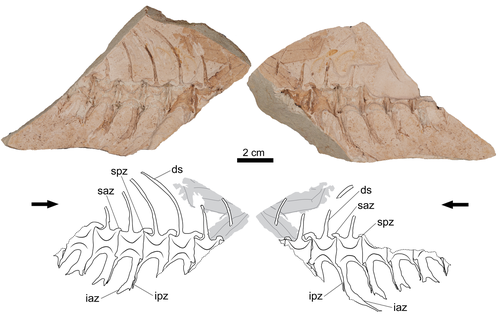

A newly discovered fossil of a tuna fish from the Miocene has been identified in the Duho Formation in Pohang City, South Korea (Suh et al., 2025). The new find, attributed to the genus Auxis, represents only the second valid fossil record of this genus globally, thus contributing to the understanding of evolutionary history within the Scombridae family (Collette and Nauen, 1983; Nam et al., 2021). The partially skeleton GNUE322001 consists of a few articulated caudal vertebrae preserving diagnostic features of the genus Auxis (Suh et al., 2025). Although it is not possible to compare the new find with the only fossil species known to date, †A. koreanus Nam et al., 2021, the significant difference in size suggests that it could be a different species. The fossil, preserved in fine-grained mudstone, also offers insights into taphonomic processes, suggesting that the specimen underwent significant decomposition in a low-energy sedimentary environment before burial. The new record of Auxis supports interpretations of the Duho Formation as a pelagic and subtropical marine habitat, shaped by upwelling activities during the Miocene (Graham and Dickson, 2000; Kim and Paik, 2013; Nam et al., 2021). This discovery emphasizes the significance of upwelling zones in fostering biodiversity and highlights the value of fossil records in reconstructing prehistoric marine ecosystems (Lalli and Parsons, 1997; Wang and Lee, 2019). References Collette, B. B., and Nauen, C. E. (1983). Scombrids of the world: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of tunas, mackerels, bonitos, and related species known to date. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Graham, J. B., and Dickson, K. A. (2000). The evolution of thunniform locomotion and heat conservation in scombrid fishes: New insights based on the morphology of Allothunnus fallai. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 129(4), 419–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00612.x Kim, J., and Paik, I. S. (2013). Chondrites from the Duho Formation (Miocene) in the Yeonil Group, Pohang Basin, Korea: Occurrences and paleoenvironmental implications. Journal of the Geological Society of Korea, 49(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.14770/jgsk.2013.49.3.407 Lalli, C. M., and Parsons, T. R. (1997). Biological oceanography: An introduction (2nd ed). Butterworth Heinemann. Nam, G.-S., Nazarkin, M. V., and Bannikov, A. F. (2021). First discovery of the genus Auxis (Actinopterygii: Scombridae) in the Neogene of South Korea. Bollettino Della Società Paleontologica Italiana, 60(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.4435/BSPI.2021.05 Suh, D., Kim, S.-H., and Nam, G.-S. (2025). A new tuna specimen (Genus Auxis) from the Duho Formation (Miocene) of South Korea. bioRxiv, 605724, ver. 5 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.29.605724 Wang, Y.-C., and Lee, M.-A. (2019). Composition and distribution of fish larvae surrounding the upwelling zone in the waters of northeastern Taiwan in summer. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 27(5), article 8. https://doi.org/10.6119/JMST.201910_27(5).0008 | A new tuna specimen (Genus *Auxis*) from the Duho Formation (Miocene) of South Korea | Dayun Suh, Su-Hwan Kim, Gi-Soo Nam | <p>A partially preserved caudal vertebrae imprint of a tuna was discovered from the Duho Formation (Miocene) of South Korea. This specimen was assigned to the genus <em>Auxis</em> and represents the second record of fossil <em>Auxis</em> found in ... |  | Fossil record, Vertebrate paleontology | Adriana López-Arbarello | 2024-08-02 07:16:42 | View | |

23 Jan 2025

New data on morphological evolution and dietary adaptations of Elephas recki from the Plio-Pleistocene Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia)Tomas Getachew Bedane, Hassane Taïsso Mackaye, Jean-Renaud Boisserie https://osf.io/preprints/paleorxiv/qexufOf elephant teeth and plants: mesowear and dental adaptations do not track in Plio-Pleistocene elephants of the Shungura formation (Omo Valley, Ethiopia)Recommended by Vera Weisbecker based on reviews by Steven Zhang and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Steven Zhang and 1 anonymous reviewer

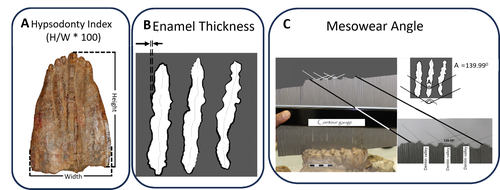

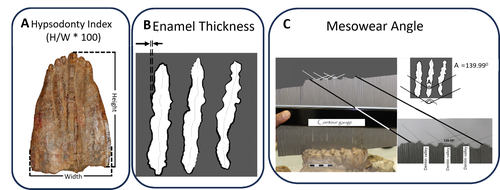

Bedane et al. (2024) provide a beautifully illustrated demonstration of the difficulties in using dental adaptation as proxies for the diets of elephants, which are in turn often used to determine the vegetation in an area. This study set out to assess mesowear, which is the relief on the teeth that forms due to abrasion by food, and therefore a good proxy of dietary composition in herbivores. The team was interested in testing whether this mesowear relates to morphological adaptations of hypsodonty (high-crownedness) and enamel thickness over a period of ~3.4–~1.1 million years in an elephant species (Elephas recki) commonly found in the Plio/Pleistocene of the Shungura formation (Omo Valley, Ethiopia). To answer this question, the team scored these metrics in 140 molars between ~3.4 and ~1.1 million years of age, separated into time bins. Their results show surprisingly low levels of variation in mesowear, indicating relatively low variation in diet that was overall mostly composed of graze (as opposed to mixed or browsing diets, which are softer). Hypsodonty and enamel thickness were correlated, but changed erratically rather than suggesting a trend towards a particular dietary adaptation. The exciting conclusion is that dental morphologies that we often consider to be adaptive to certain conditions are very slow to evolve, and that a wide variety of morphologies can support the survival of a species despite little variation in diet. For me as a functional evolutionary morphologist, this clear case of many-to-one-mapping is a timely reminder that evolution does not work either quickly or just on the one character complex I might be considering. And in terms of using elephant teeth as ecological proxies – this job clearly just got a little harder. References Bedane, T. G., Mackaye, H. T., and Boisserie, J.-R. (2025). New data on morphological evolution and dietary adaptations of Elephas recki from the Plio-Pleistocene Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia). PaleorXiv, qexuf, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/qexuf | New data on morphological evolution and dietary adaptations of *Elephas recki* from the Plio-Pleistocene Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) | Tomas Getachew Bedane, Hassane Taïsso Mackaye, Jean-Renaud Boisserie | <p style="text-align: justify;">The proboscideans, abundant and diverse throughout the Cenozoic, are essential terrestrial megaherbivores for studying morphological adaptations and reconstructing paleoenvironments in Africa. This new study of the ... |  | Fieldwork, Fossil record, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Paleoecology, Paleoenvironments, Vertebrate paleontology | Vera Weisbecker | 2024-04-24 13:32:58 | View | |

18 Dec 2024

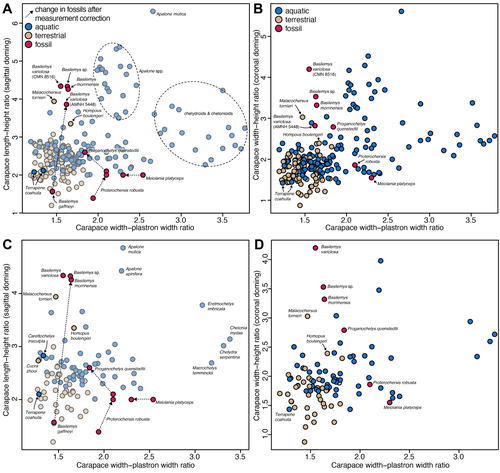

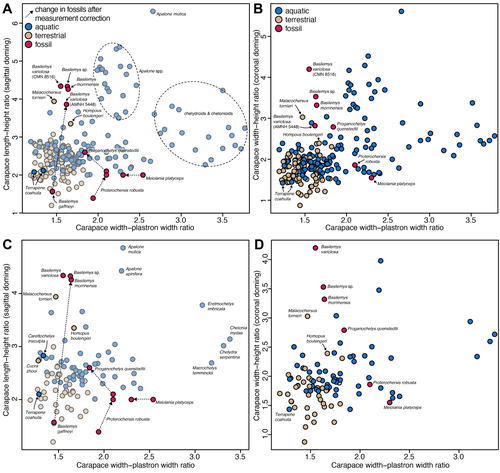

Simple shell measurements do not consistently predict habitat in turtles: a reply to Lichtig and Lucas (2017)Serjoscha W. Evers, Christian Foth, Walter G. Joyce, Guilherme Hermanson https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.25.586561Not-so-simple turtle ecomorphologyRecommended by Jordan Mallon based on reviews by Heather F. Smith and Donald BrinkmanI am a non-avian dinosaur palaeontologist by trade with a particular interest in their palaeoecology. This can be an endless source of both fascination and frustration. Fascination, because non-avian dinosaurs are quite unlike anything alive today, warranting some use of creative license when imagining them as living animals. Frustration, because the lack of good, extant ecological analogues frequently makes reconstruction of their ancient ecologies an almost insurmountable challenge. The Canadian Museum of Nature where I work has a good collection of Late Cretaceous turtles. I took an interest in these some years ago because it struck me that, despite the quality of our collection, relatively few people come to study them. I thought, "Someone should work on these. Why not me?" I figured studying a new fossil group would present a fun change of pace and perhaps a more straightforward object of palaeoecological reconstruction. After all, fossil turtles are a lot like living turtles, so how hard can it be? Right? In 2018, I took a special interest in one recently prepared fossil turtle, which I determined to be a new species of Basilemys (Mallon and Brinkman, 2018). Basilemys held my interest because, although it is a relatively common form, there has been some debate concerning the palaeohabitat of this animal and its closest relatives, the nanhsiungchelyids. Some have argued for an aquatic habitat for these animals; others, for a terrestrial one. It seems that where one comes down on the issue depends on which aspect of ecomorphology is emphasized. If it is on the flat carapace, nanhsiungchelyids must have been aquatic; if it is on the stout feet, terrestrial. This is how I came to appreciate the numerous ecomorphological proxies (e.g., skull shape, shell shape, limb proportions) that are used in turtle palaeoecology and how incongruent they can sometimes be. So much for easy answers! The present study by Evers et al. is a response to an original piece of research by Lichtig and Lucas (2017), who claimed to be able to use simple shell measurements (carapacial doming and relative plastral width) to accurately deduce/infer the habitats of living turtles and, by extension, fossil ones. In short, they found that terrestrial turtles tend to have more domed carapaces and wider plastra, yielding some unconventional palaeoecological reconstructions of particular stem turtles. Evers et al. take issue with several aspects of this study, including issues of faulty data entry, inappropriate removal of extant taxa from the model, and insufficient accounting for phylogenetic non-independence. By correcting for these overights, they find that the model of Lichtig and Lucas (2017) performs more poorly than advertised and that the palaeoecological classification it produces should be questioned. "The map is not the territory", as Alfred Korzybski put it, and this latest study by Evers et al. serves as an important reminder of that lesson. Thanks to D. Brinkman and H. Smith for their helpful reviews of the manuscript. References Evers, S. W., Foth, C., Joyce, W. G., and Hermanson, G. (2024). Simple shell measurements do not consistently predict habitat in turtles: A reply to Lichtig and Lucas (2017). bioRxiv, 586561, ver. 3 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.25.586561 Lichtig, A. J., and Lucas, S. G. (2017). A simple method for inferring habitats of extinct turtles. Palaeoworld, 26(3), 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palwor.2017.02.001 Mallon, J. C., and Brinkman, D. B. (2018). Basilemys morrinensis, a new species of nanhsiungchelyid turtle from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Alberta, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 38(2), e1431922. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2018.1431922 | Simple shell measurements do not consistently predict habitat in turtles: a reply to Lichtig and Lucas (2017) | Serjoscha W. Evers, Christian Foth, Walter G. Joyce, Guilherme Hermanson | <p>Inferring palaeoecology for fossils is a key interest of palaeobiology. For groups with extant representatives, correlations of aspects of body shape with ecology can provide important insights to understanding extinct members of lineages. The ... |  | Evolutionary biology, Macroevolution, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Paleoecology, Vertebrate paleontology | Jordan Mallon | 2024-04-19 13:31:59 | View | |

05 Sep 2024

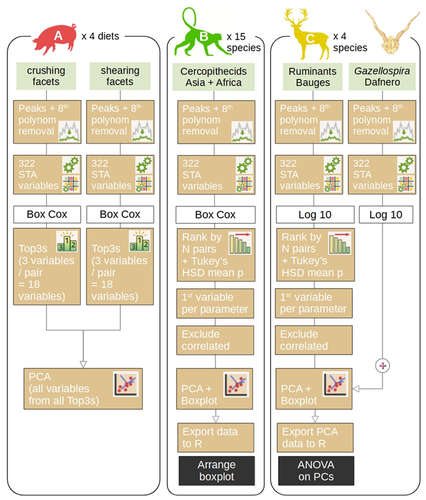

Introducing ‘trident’: a graphical interface for discriminating groups using dental microwear texture analysisThiery G., Francisco A., Louail M., Berlioz E., Blondel C., Brunetière N., Ramdarshan A., Walker A. E. C., Merceron G. https://hal.science/hal-04222508A step towards improved replicability and accessibility of 3D microwear analysesRecommended by Emilia Jarochowska based on reviews by Mugino Kubo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Mugino Kubo and 1 anonymous reviewer

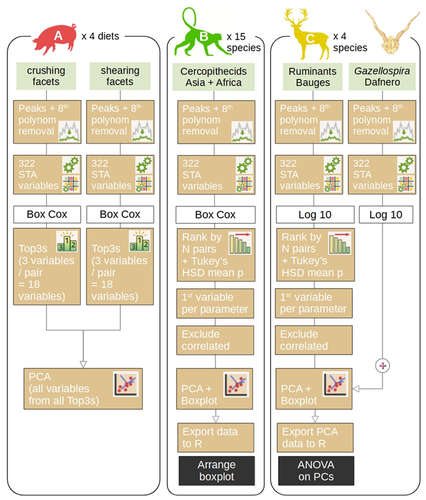

Three-dimensional microwear analysis is a very potent method in capturing the diet and, thus, reconstructing trophic relationships. It is widely applied in archaeology, palaeontology, neontology and (palaeo)anthropology. The method had been developed for mammal teeth (Walker et al., 1978; Teaford, 1988; Calandra and Merceron, 2016), but it has proven to be applicable to sharks (McLennan and Purnell, 2021) and reptiles, including fossil taxa with rather mysterious trophic ecologies (e.g., Bestwick et al., 2020; Holwerda et al., 2023). Microwear analysis has brought about landmark discoveries extending beyond autecology and reaching into palaeoenvironmental reconstructions (e.g., Merceron et al., 2016), niche evolution (e.g., Thiery et al., 2021), and assessment of food availability and niche partitioning (Ősi et al., 2022). Furthermore, microwear analysis is a testable method, which can be investigated experimentally in extant animals in order to ground-truth dietary interpretations in extinct organisms. The study by Thiery et al. (2024) addresses important limitations of 3D microwear analysis: 1) the unequal access to commercial software required to analyze surface data obtained using confocal profilometers; 2) lack of replicability resulting from the use of commercial software with graphical user interface only. The latter point results in that documenting precisely what has been analyzed and how is nearly impossible. The use of algorithms such as scale-sensitive fractal analysis (Ungar et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2006) and surface texture analysis has greatly improved replicability of DMTA and nearly eliminated intra- and inter-observer errors. Substantial effort has been made to quantify and minimize systematic and random errors in microwear analyses, such as intraspecific variation, use of different equipment (Arman et al., 2016), use of casts (Mihlbachler et al., 2019) or non-dietary variables (Bestwick et al., 2021). But even the best designed study cannot be replicated if the analysis is carried out with a “black box” software that many researchers may not afford. The trident package for R Software (https://github.com/nialsiG/trident) presented by Thiery et al. (2024) allows users to calculate 24 variables used in DMTA, transform them, calculate their variation across a surface, and rank them according to a sophisticated workflow that takes into account their normality and heteroscedasticity. A graphical user interface (GUI) is included in the form of a ShinyApp, but the power of the package, in my opinion, lies in that all steps of the analyses can be saved as R code and shared together with a study. This is a fundamental contribution to replicability and validation of microwear analyses. As best practices in code quality and replication become better known and accessible to palaeobiologists (The Turing Way Community, 2022; Trisovic et al., 2022). The presentation of the trident package is associated with three case studies, each with associated instructions on reproducing the results. These instructions partly use the literate programming approach, so that each step of the analysis is discussed and the methods are presented, either as screen shots when the GUI is used, or code. This is an excellent contribution, which hopefully will be followed by future microwear studies. References Arman, S. D., Ungar, P. S., Brown, C. A., DeSantis, L. R. G., Schmidt, C., and Prideaux, G. J. (2016). Minimizing inter-microscope variability in dental microwear texture analysis. Surface Topography: Metrology and Properties, 4(2), 024007. https://doi.org/10.1088/2051-672X/4/2/024007 Bestwick, J., Unwin, D. M., Butler, R. J., and Purnell, M. A. (2020). Dietary diversity and evolution of the earliest flying vertebrates revealed by dental microwear texture analysis. Nature Communications, 11(1), 5293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19022-2 Bestwick, J., Unwin, D. M., Henderson, D. M., and Purnell, M. A. (2021). Dental microwear texture analysis along reptile tooth rows: Complex variation with non-dietary variables. Royal Society Open Science, 8(2), 201754. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201754 Calandra, I., and Merceron, G. (2016). Dental microwear texture analysis in mammalian ecology. Mammal Review, 46(3), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12063 Holwerda, F. M., Bestwick, J., Purnell, M. A., Jagt, J. W. M., and Schulp, A. S. (2023). Three-dimensional dental microwear in type-Maastrichtian mosasaur teeth (Reptilia, Squamata). Scientific Reports, 13(1), 18720. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42369-7 McLennan, L. J., and Purnell, M. A. (2021). Dental microwear texture analysis as a tool for dietary discrimination in elasmobranchs. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 2444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81258-9 Merceron, G., Novello, A., and Scott, R. S. (2016). Paleoenvironments inferred from phytoliths and Dental Microwear Texture Analyses of meso-herbivores. Geobios, 49(1–2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2016.01.004 Mihlbachler, M. C., Foy, M., and Beatty, B. L. (2019). Surface replication, fidelity and data loss in traditional dental microwear and dental microwear texture analysis. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37682-5 Ősi, A., Barrett, P. M., Evans, A. R., Nagy, A. L., Szenti, I., Kukovecz, Á., Magyar, J., Segesdi, M., Gere, K., and Jó, V. (2022). Multi-proxy dentition analyses reveal niche partitioning between sympatric herbivorous dinosaurs. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 20813. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24816-z Scott, R. S., Ungar, P. S., Bergstrom, T. S., Brown, C. A., Childs, B. E., Teaford, M. F., and Walker, A. (2006). Dental microwear texture analysis: Technical considerations. Journal of Human Evolution, 51(4), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.006 Teaford, M. F. (1988). A review of dental microwear and diet in modern mammals. Scanning Microscopy, 2, 1149–1166. The Turing Way Community. (2022). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (Version 1.0.2). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3233853 Thiery, G., Francisco, A., Louail, M., Berlioz, É., Blondel, C., Brunetière, N., Ramdarshan, A., Walker, A. E. C., and Merceron, G. (2024). Introducing “trident”: A graphical interface for discriminating groups using dental microwear texture analysis. HAL, hal-04222508, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://hal.science/hal-04222508v4 Thiery, G., Gibert, C., Guy, F., Lazzari, V., Geraads, D., Spassov, N., and Merceron, G. (2021). From leaves to seeds? The dietary shift in late Miocene colobine monkeys of southeastern Europe. Evolution, 75(8), 1983–1997. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14283 Trisovic, A., Lau, M. K., Pasquier, T., and Crosas, M. (2022). A large-scale study on research code quality and execution. Scientific Data, 9(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01143-6 Ungar, P. S., Brown, C. A., Bergstrom, T. S., and Walker, A. (2003). Quantification of dental microwear by tandem scanning confocal microscopy and scale‐sensitive fractal analyses. Scanning, 25(4), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/sca.4950250405 Walker, A., Hoeck, H. N., and Perez, L. (1978). Microwear of mammalian teeth as an indicator of diet. Science, 201(4359), 908–910. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.684415 | Introducing ‘trident’: a graphical interface for discriminating groups using dental microwear texture analysis | Thiery G., Francisco A., Louail M., Berlioz E., Blondel C., Brunetière N., Ramdarshan A., Walker A. E. C., Merceron G. | <p>This manuscript introduces trident, an R package for performing dental microwear texture analysis and subsequently classifying variables based on their ability to separate discrete categories. Dental microwear textures reflect the physical prop... |  | Paleoecology, Vertebrate paleontology | Emilia Jarochowska | 2023-09-30 22:56:03 | View | |

13 Aug 2024

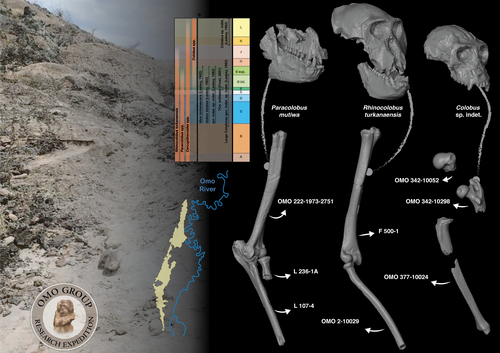

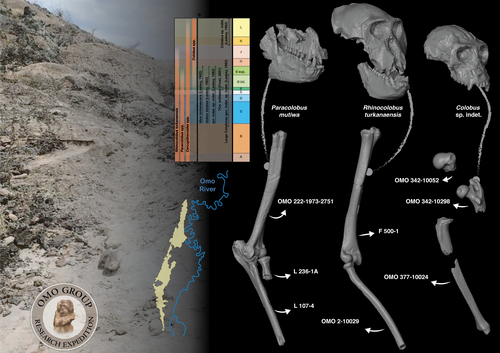

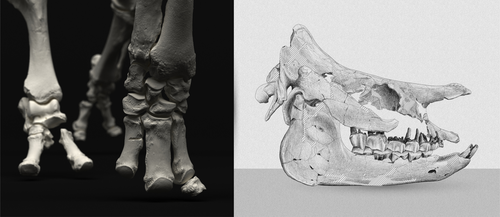

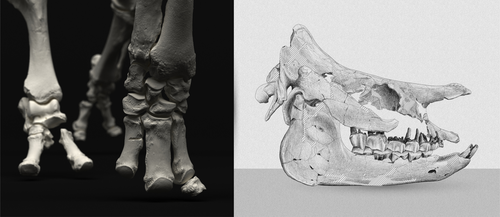

Postcranial anatomy of the long bones of colobines (Mammalia, Primates) from the Plio-Pleistocene Omo Group deposits (Shungura Formation and Usno Formation, 1967-2018 field campaigns, Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia)Laurent Pallas, Guillaume Daver, Gildas Merceron, Jean-Renaud Boisserie https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/bwegtPostcrania from the Shungura and Usno Formations (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) provide new insights into evolution of colobine monkeys (Primates, Cercopithecidae)Recommended by Stephen Frost based on reviews by Monya Anderson and 1 anonymous reviewerIn their analysis, Pallas and colleagues identify 32 postcranial elements from the Plio-Pleistocene collections of the Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia as colobine (Pallas et al., 2024). This is a valuable contribution towards understanding colobine evolution, Plio-Pleistocene environments of the Turkana Basin, Kenya and Ethiopia, and how the many large-bodied catarrhines, including at least three hominins, four colobines, and three papionins, all with body masses over 30 Kg shared this ecosystem. Today, colobine monkeys have greater diversity in Asia than in Africa, where they are represented by three small to medium-sized forms: olive, red, and black and white colobus (Grubb et al., 2003; Roos and Zinner, 2022). In the Pliocene and Pleistocene, however, they were significantly more diverse, with at least four additional large-bodied genera that varied considerably in body size, and as evidenced by multiple proxies, their preferred habitats, diets, and locomotor behaviors (Frost et al., 2022 and references therein). The highly fossiliferous sediments of the Shungura and Usno Formations in the Lower Omo Valley span the period from 3.75 to 1.0 Ma (Heinzelin, 1983; McDougall et al., 2012; Kidane et al., 2014) and have contributed greatly to understanding human and mammalian evolution during the African Plio-Pleistocene (Howell and Coppens, 1974; Boisserie et al., 2008), including the enigmatic large-bodied colobines (Leakey, 1982; 1987). Despite large samples of postcranial material from the Lower Omo Valley (Eck, 1977), most of our knowledge of fossil colobine postcrania is based on a relatively few associated skeletons from other eastern African sites (Birchette, 1982; Frost and Delson, 2002; Jablonski et al., 2008; Anderson, 2021). This is because the vast majority of postcrania from the Lower Omo Valley are not directly associated with taxonomically diagnostic elements. Based on qualitative and quantitative comparison with an extensive database of extant cercopithecoid postcrania, Pallas et al. (2024) identify 32 long bones of the fore- and hindlimbs as colobine. These range in age from approximately 3.3 to 1.1 Ma. They made their identifications using a combination of body mass estimation and comparison with associated skeletons of Plio-Pleistocene and extant taxa. In this way, they tentatively allocate some of the larger material dated to 3.3. to 2.0 Ma to taxa previously recognized from craniodental remains, especially Rhinocolobus cf. turkanaensis and Paracolobus cf. mutiwa; and the smaller ca. 1.1 Ma to cf. Colobus. Interestingly, they also identify several specimens, especially from Members B and C, that are unlikely to represent taxa previously described for the Lower Omo Valley and make a possible link to Cercopithecoides meaveae, otherwise only known from the Afar Region, Ethiopia (Frost and Delson, 2002). Based on these identifications, Pallas et al. (2024) hypothesize that Rhinocolobus may have been adapted to more suspensory postures compared to Cercopithecoides and Paracolobus which are estimated to have been more terrestrial. Additionally, they suggest that the possibly semi-terrestrial Paracolobus mutiwa may show adaptations for vertical climbing. These are novel observations, and if they are correct give further clues as to how these primates seemingly managed to co-exist in the same area for nearly a million years (Leakey, 1982; 1987; Jablonski et al., 2008). Better understanding the locomotor and positional behaviors of these taxa will also make them more useful in reconstructions of the paleoenvironments represented by the Shungura and Usno Formations. References Anderson, M. (2021). An assessment of the postcranial skeleton of the Paracolobus mutiwa (Primates: Colobinae) specimen KNM-WT 16827 from Lomekwi, West Turkana, Kenya. Journal of Human Evolution, 156, 103012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2021.103012 Birchette, M. G. (1982). The postcranial skeleton of Paracolobus chemeroni [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Harvard University. Boisserie, J.-R., Guy, F., Delagnes, A., Hlukso, L. J., Bibi, F., Beyene, Y., and Guillemot, C. (2008). New palaeoanthropological research in the Plio-Pleistocene Omo Group, Lower Omo Valley, SNNPR (Southern Nations, Nationalities and People Regions), Ethiopia. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 7(7), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2008.07.010 Eck, G. (1977). Diversity and frequency distribution of Omo Group Cercopithecoidea. Journal of Human Evolution, 6(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2484(77)80041-9 Frost, S. R., and Delson, E. (2002). Fossil Cercopithecidae from the Hadar Formation and surrounding areas of the Afar Depression, Ethiopia. Journal of Human Evolution, 43(5), 687–748. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.2002.0603 Frost, S. R., Gilbert, C. C., and Nakatsukasa, M. (2022). The colobine fossil record. In I. Matsuda, C. C. Grueter, and J. A. Teichroeb (Eds.), The Colobines: Natural History, Behaviour and Ecological Diversity. Cambridge University Press. Pp. 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108347150 Grubb, P., Butynski, T. M., Oates, J. F., Bearder, S. K., Disotell, T. R., Groves, C. P., and Struhsaker, T. T. (2003). Assessment of the diversity of African primates. International Journal of Primatology, 24(6), 1301–1357. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IJOP.0000005994.86792.b9 Heinzelin, J. de. (1983). The Omo Group. Archives of the International Omo Research Expedition. Volume 85. Annales du Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, série 8, Sciences géologiques, Tervuren, 388 p. Howell, F. C., and Coppens, Y. (1974). Inventory of remains of Hominidae from Pliocene/Pleistocene formations of the lower Omo basin, Ethiopia (1967–1972). American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 40(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330400102 Jablonski, N. G., Leakey, M. G., Ward, C. V., and Antón, M. (2008). Systematic paleontology of the large colobines. In N. G. Jablonski and M. G. Leakey (Eds.), Koobi Fora Research Project Volume 6: The Fossil Monkeys. California Academy of Sciences. Pp. 31–102. Kidane, T., Brown, F. H., and Kidney, C. (2014). Magnetostratigraphy of the fossil-rich Shungura Formation, southwest Ethiopia. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 97, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2014.05.005 Leakey, M. G. (1982). Extinct large colobines from the Plio‐Pleistocene of Africa. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 58(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330580207 Leakey, M. G. (1987). Colobinae (Mammalia, Primates) from the Omo Valley, Ethiopia. In Y. Coppens and F. C. Howell (Eds.), Les faunes Plio-Pléistocènes de la Basse Vallée de l’Omo (Ethiopie). Tome 3, Cercopithecidae de la Formation de Shungura. CNRS, Paris, pp. 148-169. McDougall, I., Brown, F. H., Vasconcelos, P. M., Cohen, B. E., Thiede, D. S., and Buchanan, M. J. (2012). New single crystal 40Ar/39Ar ages improve time scale for deposition of the Omo Group, Omo–Turkana Basin, East Africa. Journal of the Geological Society, 169(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1144/0016-76492010-188 Pallas, L., Daver, G., Merceron, G., and Boisserie, J.-R. (2024). Postcranial anatomy of the long bones of colobines (Mammalia, Primates) from the Plio-Pleistocene Omo Group deposits (Shungura Formation and Usno Formation, 1967-2018 field campaigns, Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia). PaleorXiv, bwegt, ver. 8, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/bwegt Roos, C., and Zinner, D. (2022). Molecular phylogeny and phylogeography of colobines. In I. Matsuda, C. C. Grueter, and J. A. Teichroeb (Eds.), The Colobines: Natural History, Behaviour and Ecological Diversity. Cambridge University Press. Pp. 32-43. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108347150

| Postcranial anatomy of the long bones of colobines (Mammalia, Primates) from the Plio-Pleistocene Omo Group deposits (Shungura Formation and Usno Formation, 1967-2018 field campaigns, Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) | Laurent Pallas, Guillaume Daver, Gildas Merceron, Jean-Renaud Boisserie | <p style="text-align: justify;">Our knowledge of the functional and taxonomic diversity of the fossil colobine fauna (Colobinae Jerdon, 1867) from the Lower Omo Valley is based only on craniodental remains. Here we describe postcranial specimens o... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary patterns and dynamics, Fossil record, Macroevolution, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Paleobiology, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Stephen Frost | 2023-02-05 06:01:30 | View | |

03 Jul 2024

Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successionsNiklas Hohmann, Joel R. Koelewijn, Peter Burgess, Emilia Jarochowska https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.18.572098Advances in understanding how stratigraphic structure impacts inferences of phenotypic evolutionRecommended by Melanie Hopkins based on reviews by Bjarte Hannisdal, Katharine Loughney, Gene Hunt and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bjarte Hannisdal, Katharine Loughney, Gene Hunt and 1 anonymous reviewer

A fundamental question in evolutionary biology and paleobiology is how quickly populations and/or species evolve and under what circumstances. Because the fossil record affords us the most direct view of how species lineages have changed in the past, considerable effort has gone into developing methodological approaches for assessing rates of evolution as well as what has been termed “mode of evolution” which generally describes pattern of evolution, for example whether the morphological change captured in fossil time series are best characterized as static, punctuated, or trending (e.g., Sheets and Mitchell, 2001; Hunt, 2006, 2008; Voje et al., 2018). The rock record from which these samples are taken, however, is incomplete, due to spatially and temporally heterogenous sediment deposition and erosion. The resulting structure of the stratigraphic record may confound the direct application of evolutionary models to fossil time series, most of which come from single localities. This pressing issue is tackled in a new study entitled “Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions” (Hohmann et al., 2024). The “carbonate successions” part of the title is important. Previous similar work (Hannisdal, 2006) used models for siliciclastic depositional systems to simulate the rock record. Here, the authors simulate sediment deposition across a carbonate platform, a system that has been treated as fundamentally different from siliciclastic settings, from both the point of view of geology (see Wagoner et al., 1990; Schlager, 2005) and ecology (Hopkins et al., 2014). The authors do find that stratigraphic structure impacts the identification of mode of evolution but not necessarily in the way one might expect; specifically, it is less important how much time is represented compared to the size and distribution of gaps, regardless of where you are sampling along the platform. This result provides an important guiding principle for selecting fossil time series for future investigations. Another very useful result of this study is the impact of time series length, which in this case should be understood as the density of sampling over a particular time interval. Counterintuitively, the probability of selecting the data-generating model as the best model decreases with increased length. The authors propose several explanations for this, all of which should inspire further work. There are also many other variables that could be explored in the simulations of the carbonate models as well as the fossil time series. For example, the authors chose to minimize within-sample variation in order to avoid conflating variability with evolutionary trends. But greater variance also potentially impacts model selection results and underlies questions about how variation relates to evolvability and the potential for directional change. Lastly, readers of Hohmann et al. (2024) are encouraged to also peruse the reviews and author replies associated with the PCI Paleo peer review process. The discussion contained in these documents touch on several important topics, including model performance and model selection, the nature of nested model systems, and the potential of the forwarding modeling approach. References Hannisdal, B. (2006). Phenotypic evolution in the fossil record: Numerical experiments. The Journal of Geology, 114(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1086/499569 Hohmann, N., Koelewijn, J. R., Burgess, P., and Jarochowska, E. (2024). Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions. bioRxiv, 572098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.18.572098 Hopkins, M. J., Simpson, C., and Kiessling, W. (2014). Differential niche dynamics among major marine invertebrate clades. Ecology Letters, 17(3), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12232 Hunt, G. (2006). Fitting and comparing models of phyletic evolution: Random walks and beyond. Paleobiology, 32(4), 578–601. https://doi.org/10.1666/05070.1 Hunt, G. (2008). Gradual or pulsed evolution: When should punctuational explanations be preferred? Paleobiology, 34(3), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1666/07073.1 Schlager, W. (Ed.). (2005). Carbonate Sedimentology and Sequence Stratigraphy. SEPM Concepts in Sedimentology and Paleontology No. 8. https://doi.org/10.2110/csp.05.08 Sheets, H. D., and Mitchell, C. E. (2001). Why the null matters: Statistical tests, random walks and evolution. Genetica, 112, 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013308409951 Voje, K. L., Starrfelt, J., and Liow, L. H. (2018). Model adequacy and microevolutionary explanations for stasis in the fossil record. The American Naturalist, 191(4), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/696265 Wagoner, J. C. V., Mitchum, R. M., Campion, K. M., and Rahmanian, V. D. (1990). Siliciclastic Sequence Stratigraphy in Well Logs, Cores, and Outcrops: Concepts for High-Resolution Correlation of Time and Facies. AAPG Methods in Exploration Series No. 7. https://doi.org/10.1306/Mth7510 | Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions | Niklas Hohmann, Joel R. Koelewijn, Peter Burgess, Emilia Jarochowska | <p><strong>Background:</strong> The fossil record provides the unique opportunity to observe evolution over millions of years, but is known to be incomplete. While incompleteness varies spatially and is hard to estimate for empirical sections, com... | Evolutionary biology, Evolutionary patterns and dynamics, Fossil record, Methods, Sedimentology | Melanie Hopkins | 2023-12-19 08:10:00 | View | ||

04 Jun 2024

New generic name for a small Triassic ray-finned fish from Perledo (Italy)Adriana López-Arbarello, Rainer Brocke https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/bxmg5A new study on the halecomorph fishes from the Triassic of Perledo (Italy) highlights important issues in PalaeoichthyologyRecommended by Hugo Martín Abad based on reviews by Guang-Hui Xu and 1 anonymous reviewerMesozoic fishes are extremely diverse. In fact, fishes are the most diverse group of vertebrates during the Mesozoic─just as during any other era. Yet, their study is severely underrepresented in comparison to other fossil groups. There are just too few palaeoichthyologists to deal with such a vast diversity of fishes. Nonetheless, thanks to the huge efforts they have made over the last few decades, we have come a long way in our understanding of Mesozoic ichthyofaunas. One of such devoted palaeoichthyologists is Dr. Adriana López-Arbarello, whose contributions have been crucial in elucidating the phylogenetic interrelationships and taxonomic diversity of Mesozoic actinopterygian fishes (e.g., López-Arbarello, 2012; López-Arbarello & Sferco, 2018; López-Arbarello & Ebert, 2023). In her most recent manuscript, Dr. López-Arbarello has joined forces with Dr. Rainer Brocke to tackle the taxonomy and systematics of the halecomorph fishes from one of the most relevant Triassic sites, the upper Ladinian Perledo locality from Italy (López-Arbarello & Brocke, 2024). Fossil fishes were reported for the first time from Perledo in the first half of the 19th century (Balsamo-Crivelli, 1839), and up to 30 different species were described from the locality in the subsequent decades. Unfortunately, this is one of the multiple examples of fossil collections that suffered the effects of World War II, and most of the type material was lost. As a consequence, many of those 30 species that have been described over the years are in need of a revision. Based on the study of additional material that was transferred to Germany and is housed at the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum, López-Arbarello & Brocke (2024) confirm the presence of four different species of halecomorph fishes in Perledo, which were previously put under synonymy (Lombardo, 2001). They provide new detailed information on the anatomy of two of those species, together with their respective diagnoses. But more importantly, they carry out a thorough exercise of taxonomy, rigorously applying the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature to disentangle the intricacies in the taxonomic story of the species placed in the genus Allolepidotus. As a result, they propose the presence of the species A. ruppelii, which they propose to be the type species for that genus (instead of A. bellottii, which they transfer to the genus Eoeugnathus). They also propose a new genus for the other species originally included in Allolepidotus, A. nothosomoides. Finally, they provide a set of measurements and ratios for Pholidophorus oblongus and Pholidophorus curionii, the other two species previously put in synonymy with A. bellottii, to demonstrate their validity as different species. However, due to the loss of the type material, the authors propose that these two species remain as nomina dubia. In summary, apart from providing new detailed anatomical descriptions of two species and solving some long-standing issues with the taxonomy of the halecomorphs from the relevant Triassic Perledo locality, the paper by López-Arbarello & Rainer (2024) highlights three important topics for the study of the fossil record: 1) we should never forget that world-scale problems, such as World Wars, also affect our capacity to understand the natural world in which we live, and the whole society should be aware if this; 2) the importance of exhaustively following the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature when describing new species; and 3) we are in need of new palaeoichthyologists to, in Dr. López-Arbarello’s own words, “unveil the mysteries of those marvellous Mesozoic ichthyofaunas.” References Balsamo-Crivelli, G. (1839). Descrizione di un nuovo rettile fossile, della famiglia dei Paleosauri, e di due pesci fossili, trovati nel calcare nero, sopra Varenna sul lago di Como, dal nobile sig. Ludovico Trotti, con alcune riflessioni geologiche. Il politecnico repertorio mensile di studj applicati alla prosperita e coltura sociale, 1, 421–431. Lombardo, C. (2001). Actinopterygians from the Middle Triassic of northern Italy and Canton Ticino (Switzerland): Anatomical descriptions and nomenclatural problems. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 107, 345–369. https://doi.org/10.13130/2039-4942/5439 López-Arbarello, A. (2012). Phylogenetic interrelationships of ginglymodian fishes (Actinopterygii: Neopterygii). PLOS ONE, 7(7), e39370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039370 López-Arbarello, A., and Brocke, R. (2024). New generic name for a small Triassic ray-finned fish from Perledo (Italy). PaleorXiv, bxmg5, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/bxmg5 López-Arbarello, A., and Ebert, M. (2023). Taxonomic status of the caturid genera (Halecomorphi, Caturidae) and their Late Jurassic species. Royal Society Open Science, 10(1), 221318. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.221318 López-Arbarello, A., and Sferco, E. (2018). Neopterygian phylogeny: The merger assay. Royal Society Open Science, 5(3), 172337. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.172337 | New generic name for a small Triassic ray-finned fish from Perledo (Italy) | Adriana López-Arbarello, Rainer Brocke | <p>Our new study of the species originally included in the genus <em>Allolepidotus</em> led to the taxonomic revision of the halecomorph species from the Triassic of Perledo, Italy. The morphological variation revealed by the analysis of the type ... |  | Fossil record, Systematics, Taxonomy, Vertebrate paleontology | Hugo Martín Abad | 2024-03-21 11:53:53 | View | |

26 Apr 2024

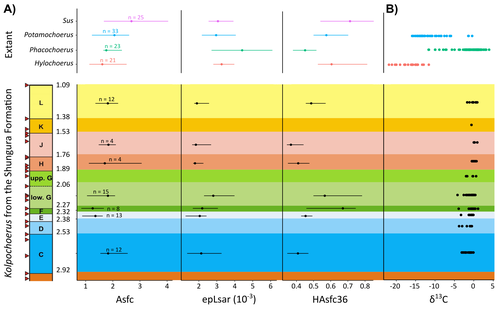

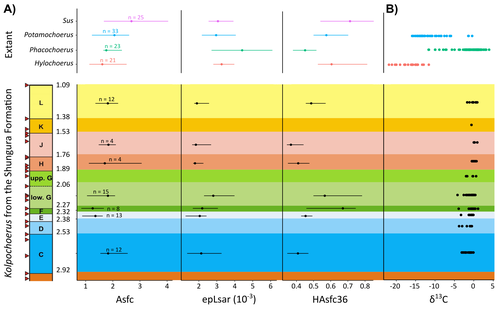

New insights on feeding habits of Kolpochoerus from the Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) using dental microwear texture analysisMargot Louail, Antoine Souron, Gildas Merceron, Jean-Renaud Boisserie https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/dbgtpDental microwear texture analysis of suid teeth from the Shungura Formation of the Omo Valley, EthiopiaRecommended by Denise Su based on reviews by Daniela E. Winkler and Kari PrassackSuidae are well-represented in Plio-Pleistocene African hominin sites and are particularly important for biochronological assessments. Their ubiquity in hominin sites combined with multiple appearances of what appears to be graminivorous adaptations in the lineage (Harris & White, 1979) suggest that they have the potential to contribute to our understanding of Plio-Pleistocene paleoenvironments. While they have been generally understudied in this respect, there has been recent focus on their diets to understand the paleoenvironments of early hominin habitats. Of particular interest is Kolpochoerus, one of the most abundant suid genera in the Plio-Pleistocene with a wide geographic distribution and diverse dental morphologies (Harris & White, 1979). In this study, Louail et al. (2024) present the results of the first dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA) conducted on suids from the Shungura Formation of the Omo Valley, an important Plio-Pleistocene hominin site that records an almost continuous sedimentary record from ca. 3.75 Ma to 1.0 Ma (Heinzelin 1983; McDougall et al., 2012; Kidane et al., 2014). Dental microwear is one of the main proxies in understanding diet in fossil mammals, particularly herbivores, and DMTA has been shown to be effective in differentiating inter- and intra-species dietary differences (e.g., Scott et al., 2006; 2012; Merceron et al., 2010). However, only a few studies have applied this method to extinct suids (Souron et al., 2015; Ungar et al., 2020), making this study especially pertinent for those interested in suid dietary evolution or hominin paleoecology. In addition to examining DMT variations of Kolpochoerus specimens from Omo, Louail et al. (2024) also expanded the modern comparative data set to include larger samples of African suids with different diets from herbivores to omnivores to better interpret the fossil data. They found that DMTA distinguishes between extant suid taxa, reflecting differences in diet, indicating that DMT can be used to examine the diets of fossil suids. The results suggest that Kolpochoerus at Omo had a substantially different diet from any extant suid taxon and that although its anistropy values increased through time, they remain well below those observed in modern Phacochoerus that specializes in fibrous, abrasive plants. Based on these results, in combination with comparative and experimental DMT, enamel carbon isotopic, and morphological data, Louail et al. (2024) propose that Omo Kolpochoerus preferred short, soft and low abrasive herbaceous plants (e.g., fresh grass shoots), probably in more mesic habitats. Louail et al. (2024) note that with the wide temporal and geographic distribution of Kolpochoerus, different species and populations may have had different feeding habits as they exploited different local habitats. However, it is noteworthy that similar inferences were made at other hominin sites based on other types of dietary data (e.g., Harris & Cerling, 2002; Rannikko et al., 2017, 2020; Yang et al., 2022). If this is an indication of their habitat preferences, the wide-ranging distribution of Kolpochoerus may suggest that mesic habitats with short, soft herbaceous plants were present in various proportions at most Plio-Pleistocene hominin sites. References Harris, J. M., and Cerling, T. E. (2002). Dietary adaptations of extant and Neogene African suids. Journal of Zoology, 256(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952836902000067 Harris, J. M., and White, T. D. (1979). Evolution of the Plio-Pleistocene African Suidae. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 69(2), 1–128. https://doi.org/10.2307/1006288 Heinzelin, J. de. (1983). The Omo Group. Archives of the International Omo Research Expedition. Volume 85. Annales du Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, série 8, Sciences géologiques, Tervuren, 388 p. Kidane, T., Brown, F. H., and Kidney, C. (2014). Magnetostratigraphy of the fossil-rich Shungura Formation, southwest Ethiopia. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 97, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2014.05.005 Louail, M., Souron, A., Merceron, G., and Boisserie, J.-R. (2024). New insights on feeding habits of Kolpochoerus from the Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) using dental microwear texture analysis. PaleorXiv, dbgtp, ver. 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/dbgtp McDougall, I., Brown, F. H., Vasconcelos, P. M., Cohen, B. E., Thiede, D. S., and Buchanan, M. J. (2012). New single crystal 40Ar/39Ar ages improve time scale for deposition of the Omo Group, Omo–Turkana Basin, East Africa. Journal of the Geological Society, 169(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1144/0016-76492010-188 Merceron, G., Escarguel, G., Angibault, J.-M., and Verheyden-Tixier, H. (2010). Can dental microwear textures record inter-individual dietary variations? PLoS ONE, 5(3), e9542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009542 Rannikko, J., Adhikari, H., Karme, A., Žliobaitė, I., and Fortelius, M. (2020). The case of the grass‐eating suids in the Plio‐Pleistocene Turkana Basin: 3D dental topography in relation to diet in extant and fossil pigs. Journal of Morphology, 281(3), 348–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.21103 Rannikko, J., Žliobaitė, I., and Fortelius, M. (2017). Relative abundances and palaeoecology of four suid genera in the Turkana Basin, Kenya, during the late Miocene to Pleistocene. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 487, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.08.033 Scott, R. S., Teaford, M. F., and Ungar, P. S. (2012). Dental microwear texture and anthropoid diets. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 147(4), 551–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22007 Scott, R. S., Ungar, P. S., Bergstrom, T. S., Brown, C. A., Childs, B. E., Teaford, M. F., and Walker, A. (2006). Dental microwear texture analysis: Technical considerations. Journal of Human Evolution, 51(4), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.006 Souron, A., Merceron, G., Blondel, C., Brunetière, N., Colyn, M., Hofman-Kamińska, E., and Boisserie, J.-R. (2015). Three-dimensional dental microwear texture analysis and diet in extant Suidae (Mammalia: Cetartiodactyla). Mammalia, 79(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/mammalia-2014-0023 Ungar, P. S., Abella, E. F., Burgman, J. H. E., Lazagabaster, I. A., Scott, J. R., Delezene, L. K., Manthi, F. K., Plavcan, J. M., and Ward, C. V. (2020). Dental microwear and Pliocene paleocommunity ecology of bovids, primates, rodents, and suids at Kanapoi. Journal of Human Evolution, 140, 102315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.03.005 Yang, D., Pisano, A., Kolasa, J., Jashashvili, T., Kibii, J., Gomez Cano, A. R., Viriot, L., Grine, F. E., and Souron, A. (2022). Why the long teeth? Morphometric analysis suggests different selective pressures on functional occlusal traits in Plio-Pleistocene African suids. Paleobiology, 48(4), 655–676. https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2022.11 | New insights on feeding habits of *Kolpochoerus* from the Shungura Formation (Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia) using dental microwear texture analysis | Margot Louail, Antoine Souron, Gildas Merceron, Jean-Renaud Boisserie | <p>During the Neogene and the Quaternary, African suids show dental morphological changes considered to reflect adaptations to increasing specialization on graminivorous diets, notably in the genus <em>Kolpochoerus</em>. They tend to exhibit elong... |  | Paleoecology, Vertebrate paleontology | Denise Su | 2023-08-28 10:38:33 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event"Melanie A. D. During, Dennis F. A. E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/fu7rpQuestioning isotopic data from the end-CretaceousRecommended by Christina Belanger based on reviews by Thomas Cullen and 1 anonymous reviewerBeing able to follow the evidence and verify results is critical if we are to be confident in the findings of a scientific study. Here, During et al. (2024) comment on DePalma et al. (2021) and provide a detailed critique of the figures and methods presented that caused them to question the veracity of the isotopic data used to support a spring-time Chicxulub impact at the end-Cretaceous. Given DePalma et al. (2021) did not include a supplemental file containing the original isotopic data, the suspicions rose to accusations of data fabrication (Price, 2022). Subsequent investigations led by DePalma’s current academic institution, The University of Manchester, concluded that the study contained instances of poor research practice that constitute research misconduct, but did not find evidence of fabrication (Price, 2023). Importantly, the overall conclusions of DePalma et al. (2021) are not questioned and both the DePalma et al. (2021) study and a study by During et al. (2022) found that the end-Cretaceous impact occurred in spring. During et al. (2024) also propose some best practices for reporting isotopic data that can help future authors make sure the evidence underlying their conclusions are well documented. Some of these suggestions are commonly reflected in the methods sections of papers working with similar data, but they are not universally required of authors to report. Authors, research mentors, reviewers, and editors, may find this a useful set of guidelines that will help instill confidence in the science that is published. References DePalma, R. A., Oleinik, A. A., Gurche, L. P., Burnham, D. A., Klingler, J. J., McKinney, C. J., Cichocki, F. P., Larson, P. L., Egerton, V. M., Wogelius, R. A., Edwards, N. P., Bergmann, U., and Manning, P. L. (2021). Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 23704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03232-9 During, M. A. D., Smit, J., Voeten, D. F. A. E., Berruyer, C., Tafforeau, P., Sanchez, S., Stein, K. H. W., Verdegaal-Warmerdam, S. J. A., and Van Der Lubbe, J. H. J. L. (2022). The Mesozoic terminated in boreal spring. Nature, 603(7899), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04446-1 During, M. A. D., Voeten, D. F. A. E., and Ahlberg, P. E. (2024). Calibrations without raw data—A response to “Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event.” OSF Preprints, fu7rp, ver. 5, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/fu7rp Price, M. (2022). Paleontologist accused of fraud in paper on dino-killing asteroid. Science, 378(6625), 1155–1157. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg2855 Price, M. (2023). Dinosaur extinction researcher guilty of research misconduct. Science, 382(6676), 1225–1225. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn4967 | Calibrations without raw data - a response to "Seasonal calibration of the end-cretaceous Chicxulub impact event" | Melanie A. D. During, Dennis F. A. E. Voeten, Per E. Ahlberg | <p>A recent paper by DePalma et al. reported that the season of the End-Cretaceous mass extinction was confined to spring/summer on the basis of stable isotope analyses and supplementary observations. An independent study that was concurrently und... | Fossil calibration, Geochemistry, Methods, Vertebrate paleontology | Christina Belanger | 2023-06-22 10:43:31 | View | ||

07 Mar 2024

An Early Miocene skeleton of Brachydiceratherium Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratinesAlexander Sizov, Alexey Klementiev, Pierre-Olivier Antoine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.06.498987A Rhino from Lake BaikalRecommended by Faysal Bibi based on reviews by Jérémy Tissier, Panagiotis Kampouridis and Tao Deng based on reviews by Jérémy Tissier, Panagiotis Kampouridis and Tao Deng

As for many groups, such as equids or elephants, the number of living rhinoceros species is just a fraction of their past diversity as revealed by the fossil record. Besides being far more widespread and taxonomically diverse, rhinos also came in a greater variety of shapes and sizes. Some of these – teleoceratines, or so-called ‘hippo-like’ rhinos – had short limbs, barrel-shaped bodies, were often hornless, and might have been semi-aquatic (Prothero et al., 1989; Antoine, 2002). Teleoceratines existed from the Oligocene to the Pliocene, and have been recorded from Eurasia, Africa, and North and Central America. Despite this large temporal and spatial presence, large gaps remain in our knowledge of this group, particularly when it comes to their phylogeny and their relationships to other parts of the rhino tree (Antoine, 2002; Lu et al., 2021). Here, Sizov et al. (2024) describe an almost complete skeleton of a teleoceratine found in 2008 on an island in Lake Baikal in eastern Russia. Dating to the Early Miocene, this wonderfully preserved specimen includes the skull and limb bones, which are described and figured in detail, and which indicate assignment to Brachydiceratherium shanwangense, a species otherwise known only from Shandong in eastern China, some 2000 km to the southeast (Wang, 1965; Lu et al., 2021). The study goes on to present a new phylogenetic analysis of the teleoceratines, the results of which have important implications for the taxonomy of fossil rhinos. Besides confirming the monophyly of Teleoceratina, the phylogeny supports the reassignment of most species previously assigned to Diaceratherium to Brachydiceratherium instead. In a field that is increasingly dominated by analyses of metadata, Sizov et al. (2024) provide a reminder of the importance of fieldwork for the discovery of fossil remains that, sometimes by virtue of a single specimen, can significantly augment our understanding of the evolution and paleobiogeography of extinct species. References Antoine, P.-O. (2002). Phylogénie et évolution des Elasmotheriina (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae). Mémoires du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 188, 1–359. Lu, X., Cerdeño, E., Zheng, X., Wang, S., & Deng, T. (2021). The first Asian skeleton of Diaceratherium from the early Miocene Shanwang Basin (Shandong, China), and implications for its migration route. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences: X, 6, 100074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaesx.2021.100074 Prothero, D. R., Guérin, C., and Manning, E. (1989). The History of the Rhinocerotoidea. In D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (Eds.), The Evolution of Perissodactyls (pp. 322–340). Oxford University Press. Sizov, A., Klementiev, A., & Antoine, P.-O. (2024). An Early Miocene skeleton of Brachydiceratherium Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratines. bioRxiv, 498987, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.06.498987 Wang, B. Y. (1965). A new Miocene aceratheriine rhinoceros of Shanwang, Shandong. Vertebrata Palasiatica, 9, 109–112.

| An Early Miocene skeleton of *Brachydiceratherium* Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratines | Alexander Sizov, Alexey Klementiev, Pierre-Olivier Antoine | <p>Hippo-like rhinocerotids, or teleoceratines, were a conspicuous component of Holarctic Miocene mammalian faunas, but their phylogenetic relationships remain poorly known. Excavations in lower Miocene deposits of the Olkhon Island (Tagay localit... |  | Biostratigraphy, Comparative anatomy, Fieldwork, Paleobiogeography, Paleogeography, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Faysal Bibi | 2022-07-07 15:27:12 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Jérémy Anquetin

Faysal Bibi

Guillaume Billet

Andrew A. Farke

Franck Guy

Leslea J. Hlusko

Melanie Hopkins

Cynthia V. Looy

Jesús Marugán-Lobón

Ilaria Mazzini

P. David Polly

Caroline A.E. Strömberg