Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 Sep 2018

Palaeobiological inferences based on long bone epiphyseal and diaphyseal structure - the forelimb of xenarthrans (Mammalia)Eli Amson & John A. Nyakatura https://doi.org/10.1101/318121Inferences on the lifestyle of fossil xenarthrans based on limb long bone inner structureRecommended by Alexandra Houssaye based on reviews by Andrew Pitsillides and 1 anonymous reviewerBone inner structure bears a strong functional signal and can be used in paleontology to make inferences about the ecology of fossil forms. The increasing use of microtomography enables to analyze both cortical and trabecular features in three dimensions, and thus in long bones to investigate the diaphyseal and epiphyseal structures. Moreover, this can now be done through quantitative, and not only qualitative analyses. Studies focusing on the diaphyseal inner structure (cortical bone and sometimes also spongious bone) of long bones are rather numerous, but essentially based on 2D sections. It is only recently that analyses of the whole diaphyseal structure have been investigated. Studies on the trabecular architecture are much rarer. Amson & Nyakatura (2018) propose a comparative quantitative analysis combining parameters of the epiphyseal trabecular architecture and of the diaphyseal structure, using phylogenetically informed discriminant analyses, and with the aim of inferring the lifestyle of extinct taxa. The group of interest is xenarthrans, one of the four major extant clades of placental mammals. Xenarthrans exhibit different lifestyles, from fully terrestrial to arboreal, and show various degrees of fossoriality. The authors analyzed forelimb long bones of some fossil sloths and made comparisons with several species of extant xenarthrans. The aim was notably to discuss the degree of arboreality and fossoriality of these fossil forms. This study is among the first ones to conjointly analyze both diaphyseal and trabecular parameters to characterize lifestyles, and the first one outside of primates. No fossil form could undoubtedly be assigned to one lifestyle exhibited by extant xenarthrans, though some previous ecological hypotheses could be corroborated. This study also raised some technical challenges, linked to the sample and to the parameters studied, and thus constitutes a great step, from which to go further. References Amson, E., & Nyakatura, J. A. (2018). Palaeobiological inferences based on long bone epiphyseal and diaphyseal structure - the forelimb of xenarthrans (Mammalia). bioRxiv, 318121, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.1101/318121 | Palaeobiological inferences based on long bone epiphyseal and diaphyseal structure - the forelimb of xenarthrans (Mammalia) | Eli Amson & John A. Nyakatura | <p>Trabecular architecture (i.e., the main orientation of the bone trabeculae, their number, mean thickness, spacing, etc.) has been shown experimentally to adapt with great accuracy and sensitivity to the loadings applied to the bone during life.... |  | Biomechanics & Functional morphology, Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Histology, Methods, Morphological evolution, Paleobiology, Vertebrate paleontology | Alexandra Houssaye | 2018-05-14 08:35:20 | View | |

07 Mar 2024

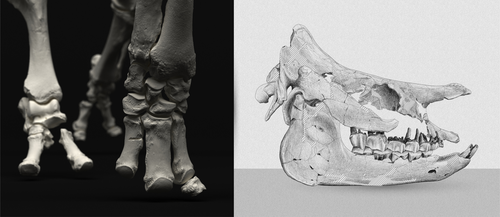

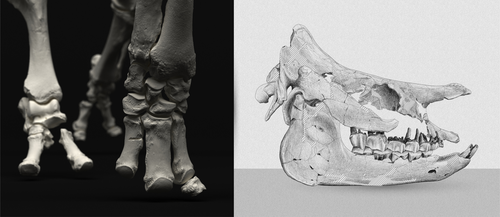

An Early Miocene skeleton of Brachydiceratherium Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratinesAlexander Sizov, Alexey Klementiev, Pierre-Olivier Antoine https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.06.498987A Rhino from Lake BaikalRecommended by Faysal Bibi based on reviews by Jérémy Tissier, Panagiotis Kampouridis and Tao Deng based on reviews by Jérémy Tissier, Panagiotis Kampouridis and Tao Deng

As for many groups, such as equids or elephants, the number of living rhinoceros species is just a fraction of their past diversity as revealed by the fossil record. Besides being far more widespread and taxonomically diverse, rhinos also came in a greater variety of shapes and sizes. Some of these – teleoceratines, or so-called ‘hippo-like’ rhinos – had short limbs, barrel-shaped bodies, were often hornless, and might have been semi-aquatic (Prothero et al., 1989; Antoine, 2002). Teleoceratines existed from the Oligocene to the Pliocene, and have been recorded from Eurasia, Africa, and North and Central America. Despite this large temporal and spatial presence, large gaps remain in our knowledge of this group, particularly when it comes to their phylogeny and their relationships to other parts of the rhino tree (Antoine, 2002; Lu et al., 2021). Here, Sizov et al. (2024) describe an almost complete skeleton of a teleoceratine found in 2008 on an island in Lake Baikal in eastern Russia. Dating to the Early Miocene, this wonderfully preserved specimen includes the skull and limb bones, which are described and figured in detail, and which indicate assignment to Brachydiceratherium shanwangense, a species otherwise known only from Shandong in eastern China, some 2000 km to the southeast (Wang, 1965; Lu et al., 2021). The study goes on to present a new phylogenetic analysis of the teleoceratines, the results of which have important implications for the taxonomy of fossil rhinos. Besides confirming the monophyly of Teleoceratina, the phylogeny supports the reassignment of most species previously assigned to Diaceratherium to Brachydiceratherium instead. In a field that is increasingly dominated by analyses of metadata, Sizov et al. (2024) provide a reminder of the importance of fieldwork for the discovery of fossil remains that, sometimes by virtue of a single specimen, can significantly augment our understanding of the evolution and paleobiogeography of extinct species. References Antoine, P.-O. (2002). Phylogénie et évolution des Elasmotheriina (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae). Mémoires du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 188, 1–359. Lu, X., Cerdeño, E., Zheng, X., Wang, S., & Deng, T. (2021). The first Asian skeleton of Diaceratherium from the early Miocene Shanwang Basin (Shandong, China), and implications for its migration route. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences: X, 6, 100074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaesx.2021.100074 Prothero, D. R., Guérin, C., and Manning, E. (1989). The History of the Rhinocerotoidea. In D. R. Prothero and R. M. Schoch (Eds.), The Evolution of Perissodactyls (pp. 322–340). Oxford University Press. Sizov, A., Klementiev, A., & Antoine, P.-O. (2024). An Early Miocene skeleton of Brachydiceratherium Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratines. bioRxiv, 498987, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.06.498987 Wang, B. Y. (1965). A new Miocene aceratheriine rhinoceros of Shanwang, Shandong. Vertebrata Palasiatica, 9, 109–112.

| An Early Miocene skeleton of *Brachydiceratherium* Lavocat, 1951 (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Baikal area, Russia, and a revised phylogeny of Eurasian teleoceratines | Alexander Sizov, Alexey Klementiev, Pierre-Olivier Antoine | <p>Hippo-like rhinocerotids, or teleoceratines, were a conspicuous component of Holarctic Miocene mammalian faunas, but their phylogenetic relationships remain poorly known. Excavations in lower Miocene deposits of the Olkhon Island (Tagay localit... |  | Biostratigraphy, Comparative anatomy, Fieldwork, Paleobiogeography, Paleogeography, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Faysal Bibi | 2022-07-07 15:27:12 | View | |

25 Oct 2022

Morphometric changes in two Late Cretaceous calcareous nannofossil lineages support diversification fueled by long-term climate changeMohammad Javad Razmjooei, Nicolas Thibault https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/nfyc9Insights into mechanisms of coccolithophore speciation: How useful is cell size in delineating species?Recommended by Emilia Jarochowska based on reviews by Andrej Spiridonov and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrej Spiridonov and 1 anonymous reviewer

Calcareous plankton gives us perhaps the most complete record of microevolutionary changes in the fossil record (e.g. Tong et al., 2018; Weinkauf et al., 2019), but this opportunity is not exploited enough, as it requires meticulous work in documenting assemblage-level variation through time. Especially in organisms such as coccolithophores, understanding the meaning of secular trends in morphology warrants an understanding of the functional biology and ecology of these organisms. Razmjooei and Thibault (2022) achieve this in their painstaking analysis of two coccolithophore lineages, Cribrosphaerella ehrenbergii and Microrhabdulus, in the Late Cretaceous of Iran. They propose two episodes of morphological change. The first one, starting around 76 Ma in the late Campanian, is marked by a sudden shift towards larger sizes of C. ehrenbergii and the appearance of a new species M. zagrosensis from M. undulatus. The second episode around 69 Ma (Maastrichtian) is inferred from a gradual size increase and morphological changes leading to probably anagenetic speciation of M. sinuosus n.sp. The study remarkably analyzed the entire distributions of coccolith length and rod width, rather than focusing on summary statistics (De Baets et al., in press). This is important, because the range of variation determines the taxon’s evolvability with respect to the considered trait (Love et al., 2022). As the authors discuss, cell size in photosymbiotic unicellular organisms is not subject to the same constraints that will be familiar to researchers working e.g. on mammals (Niklas, 1994; Payne et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2016). Furthermore, temporal changes in size alone cannot be interpreted as evolutionary without knowledge of phenotypic plasticity and environmental clines present in the basin (Aloisi, 2015). The more important is that this study cross-tests size changes with other morphological parameters to examine whether their covariation supports inferred speciation events. The article addresses as well the effects of varying sedimentation rates (Hohmann, 2021) by, somewhat implicitly, correcting for the stratophenetic trend using an age-depth model and accounting for a hiatus. Such multifaceted approach as applied in this work is fundamental to unlock the dynamics of speciation offered by the microfossil record. The study highlights also the link between shifts in size and diversity. Klug et al. (2015) have previously demonstrated that these two variables are related, as higher diversity is more likely to lead to extreme values of morphological traits, but this study suggests that the relationship is more intertwined: environmentally-driven rise in morphological variability (and thus in size) can lead to diversification. It is a fantastic illustration of the complexity of morphological evolution that, if it can be evaluated in terms of mechanisms, provides an insight into the dynamics of speciation.

References Aloisi, G. (2015). Covariation of metabolic rates and cell size in coccolithophores. Biogeosciences, 12(15), 4665–4692. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-4665-2015 De Baets, K., Jarochowska, E., Buchwald, S. Z., Klug, C., and Korn, D. (In Press). Lithology controls ammonoid size distribution. Palaios. Hohmann, N. (2021). Incorporating information on varying sedimentation rates into palaeontological analyses. PALAIOS, 36(2), 53–67. doi: 10.2110/palo.2020.038 Klug, C., De Baets, K., Kröger, B., Bell, M. A., Korn, D., and Payne, J. L. (2015). Normal giants? Temporal and latitudinal shifts of Palaeozoic marine invertebrate gigantism and global change. Lethaia, 48(2), 267–288. doi: 10.1111/let.12104 Love, A. C., Grabowski, M., Houle, D., Liow, L. H., Porto, A., Tsuboi, M., Voje, K.L., and Hunt, G. (2022). Evolvability in the fossil record. Paleobiology, 48(2), 186–209. doi: 10.1017/pab.2021.36 Niklas, K. J. (1994). Plant allometry: The scaling of form and process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Payne, J. L., Boyer, A. G., Brown, J. H., Finnegan, S., Kowalewski, M., Krause, R. A., Lyons, S.K., McClain, C.R., McShea, D.W., Novack-Gottshall, P.M., Smith, F.A., Stempien, J.A., and Wang, S. C. (2009). Two-phase increase in the maximum size of life over 3.5 billion years reflects biological innovation and environmental opportunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(1), 24–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806314106 Razmjooei, M. J., and Thibault, N. (2022). Morphometric changes in two Late Cretaceous calcareous nannofossil lineages support diversification fueled by long-term climate change. PaleorXiv, nfyc9, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/nfyc9 Smith, F. A., Payne, J. L., Heim, N. A., Balk, M. A., Finnegan, S., Kowalewski, M., Lyons, S.K., McClain, C.R., McShea, D.W., Novack-Gottshall, P.M., Anich, P.S., and Wang, S. C. (2016). Body size evolution across the Geozoic. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 44(1), 523–553. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012147 Tong, S., Gao, K., and Hutchins, D. A. (2018). Adaptive evolution in the coccolithophore Gephyrocapsa oceanica following 1,000 generations of selection under elevated CO2. Global Change Biology, 24(7), 3055–3064. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14065 Weinkauf, M. F. G., Bonitz, F. G. W., Martini, R., and Kučera, M. (2019). An extinction event in planktonic Foraminifera preceded by stabilizing selection. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0223490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223490 | Morphometric changes in two Late Cretaceous calcareous nannofossil lineages support diversification fueled by long-term climate change | Mohammad Javad Razmjooei, Nicolas Thibault | <p>Morphometric changes have been investigated in the two groups of calcareous nannofossils, <em>Cribrosphaerella ehrenbergii</em> and <em>Microrhabdulus undosus</em> across the Campanian to Maastrichtian of the Zagros Basin of Iran. Results revea... |  | Biostratigraphy, Evolutionary theory, Fossil record, Microfossils, Micropaleontology, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Nanofossils, Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoceanography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology, Paleoenvironments, Taxonomy | Emilia Jarochowska | 2020-08-29 12:23:51 | View | |

19 Aug 2021

Through a glass darkly, but with more understanding of arthropod originRecommended by Tae-Yoon Park based on reviews by Gerhard Scholtz and Jean VannierArthropods constitute 85% of all described animal species on Earth (Brusca et al., 2016), being the most successful animal phylum at present. This phylum did not even have a shabby beginning. The fossil record shows that they were dominating the sea even in the early Cambrian (Caron and Jackson, 2008; Zhao et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2019). This planet is and has been indeed dominated by arthropods. Within the context of the Big Bang of animal evolution known as the Cambrian Explosion, delving into the origin of arthropods has been one of the all-time fascinating research themes in paleontology, and discussions on the ‘origin’ and ‘early evolution’ of arthropods from the paleontological perspective have not been infrequent (e.g., Budd and Telford, 2009; Edgecombe and Legg, 2014; Daley et al., 2018; Edgecombe, 2020). In this context, Aria (2021) provides an interesting integration of his view on arthropod origin and early evolution. Based on well-preserved Burgess Shale materials, together with other impressive researches mainly with Jean-Bernard Caron (e.g., Aria and Caron, 2015; Caron and Aria, 2017), Cédric Aria made his name known with papers searching for the stem-groups of the two major euarthropod lineages, the Mandibulata and the Chelicerata (Aria and Caron, 2017, 2019), for which (and for his subsequent researches) assembling a large dataset for arthropod phylogeny was inevitable. Subsequently, there have been several major discoveries which could improve our understanding on early arthropod evolution (e.g., Lev and Chipman, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). For Cédric Aria, therefore, this timely presentation of his own perspective on the origin of early evolution of arthropods may have been preordain. This review stands out because it discusses almost all aspects of arthropod origin and early evolution that can be possibly covered by paleontology (many, if not all, of which are still controversial). Some of his views may be considered a brave attempt. For instance, based on the widespread occurrences of suspension feeders, Aria (2021) proposes the early Cambrian “planktonic revolution,” which has been associated rather with the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (Servais et al., 2016). Given the presence of lophotrochozoans and echinoderms in which the presence of planktonic larvae was likely to have been one of the most inclusive features, the “early Cambrian planktonic revolution” might be plausible, but I wonder if including arthropods into the “earlier revolution” can be readily acceptable. Arthropods arose from direct-developing ancestors, and crustaceans (the main group with planktonic larvae) are pretty much derived in the arthropod phylogenetic tree. Trilobites, inarguably the best-studied Cambrian arthropods, for example, began with direct-developing benthic protaspides in the early Cambrian and Miaolingian. The first hint of planktonic protaspides appeared in the Furongian, and it was not until the Tremadocian when such indirect developing protaspides began to be widespread (Park and Kihm, 2015), which complies well with the onset of the ‘Ordovician Planktonic Revolution’ in the Furongian, as suggested by Servais et al. (2016). But in general, this review presents well-organized views worth hearing, and since many of the points are subject to debate, this review could be a friendly manual for those who have similar views, while it could form a fresh ground to attack for those who have disparate views. One of the endless debates in arthropod research comes from the arthropod head problem (Budd, 2002), which centers on the homology of frontal-most appendages in radiodonts, megacheirans, chelicerates, and mandibulates, as well as on the hypostome-labrum complex. Based on recent interesting discoveries of early arthropods from the Chengjiang biota (Aria, 2020; Zeng et al., 2020), Aria (2021) pertinently coined a term ‘cheirae’ for the frontalmost prehensile appendages of radiodonts and megacheirans, implying homology of them. I assume that not all researchers would agree with this though, as well as with his model of hypostome/labrum complex evolution. Notorious disaccords have also occurred around the phylogenetic positions of early arthropods, such as isoxyids, megacheirans, fuxianhuiids, and artiopodans; different research groups have invariably come up with different topologies. Cédric Aria has presented his own topologies (Aria, 2019, 2020), and figure 2 of Aria (2021) summarizes his perspective very well in combination with major character evolutions. What makes this review especially interesting is a courageous discussion about the origin of biramous appendage, a subject that has been only briefly discussed or overlooked in recent literature. In the current mainstream of this debate lies the concept of ‘gilled lobopodians’ (Budd, 1998), which was complicated by the weird two separate rows of lateral flaps of Aegirocassis (Van Roy et al., 2015). Aria (2021) adds an interesting alternative scenario to this: biramicity originated from the split of main limb axis, as seen in the isoxyid Surusicaris (Aria and Caron, 2015). The figure 3d of his review, therefore, is worth giving thoughts for any arthropodologists who are interested in the origin of arthropod legs. It is true that our understanding of the origin and early evolution of arthropods is still in a mist. Nevertheless, we have recently seen advancements, such as those aided by new types of analysis (Liu et al., 2020), the discoveries of new early arthropods with unexpected morphologies (Aria et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020), and the groundbreaking Evo-Devo research (Lev and Chipman, 2020). We will keep jousting on various aspects of the origin and early evolution of arthropods, but for some aspects we are seemingly heading for the final, as implicitly alluded in Aria (2021).

References Aria C (2019). Reviewing the bases for a nomenclatural uniformization of the highest taxonomic levels in arthropods. Geological Magazine 156, 1463–1468. Aria C (2020). Macroevolutionary patterns of body plan canalization in euarthropods. Paleobiology 46, 569–593. doi: 10.1017/pab.2020.36 Aria C (2021). The origin and early evolution of arthropods. PaleorXiv, 4zmey, ver. 4, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/4zmey Aria C and Caron JB (2015). Cephalic and limb anatomy of a new isoxyid from the Burgess Shale and the role of "stem bivalved arthropods" in the disparity of the frontalmost appendage. PLOS ONE 10, e0124979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124979 Aria C and Caron JB (2017). Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan. Nature 545, 89–92. Aria C and Caron JB (2019). A middle Cambrian arthropod with chelicerae and proto-book gills. Nature 573, 586–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1525-4 Aria C, Zhao F, Zeng H, Guo J, and Zhu M (2020). Fossils from South China redefine the ancestral euarthropod body plan. BMC Evolutionary Biology 20, 4. Brusca RC, Moore W, and Shuster SM (2016). Invertebrates. Third edition. Sunderland, Massachusetts U.S.A: Sinauer Associates. isbn: 978-1-60535-375-3 Budd GE (1998). Stem-group arthropods from the Lower Cambrian Sirius Passet fauna of North Greenland. In: Arthropod Relationships. Ed. by Fortey RA and Thomas RH. London, UK: Chapman & Hall, pp. 125–138. Budd GE (2002). A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature 417, 271–275. doi: 10.1038/417271a Budd GE and Telford MJ (2009). The origin and evolution of arthropods. Nature 457, 812–817. doi: 10.1038/Nature07890 Caron JB and Aria C (2017). Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods. BMC Evolutionary Biology 17, 29. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y Caron JB and Jackson DA (2008). Paleoecology of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 258, 222–256. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.023 Daley AC, Antcliffe JB, Drage HB, and Pates S (2018). Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, 5323–5331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719962115 Edgecombe GD (2020). Arthropod origins: Integrating paleontological and molecular evidence. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 51, 1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-124437 Edgecombe GD and Legg DA (2014). Origins and early evolution of arthropods. Palaeontology 57, 457–468. Fu D, Tong G, Dai T, Liu W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Cui L, Li L, Yun H, Wu Y, Sun A, Liu C, Pei W, Gaines RR, and Zhang X (2019). The Qingjiang biota—A Burgess Shale–type fossil Lagerstätte from the early Cambrian of South China. Science 363, 1338–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8800 Lev O and Chipman AD (2020). Development of the pre-gnathal segments of the insect head indicates they are not serial homologues of trunk segments. bioRxiv, 2020.09.16.299289. doi: 10.1101/2020.09.16.299289 Liu Y, Ortega-Hernández J, Zhai D, and Hou X (2020). A reduced labrum in a Cambrian great-appendage euarthropod. Current Biology 30, 3057–3061.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.085 Park TYS and Kihm JH (2015). Post-embryonic development of the Early Ordovician (ca. 480 Ma) trilobite Apatokephalus latilimbatus Peng, 1990 and the evolution of metamorphosis. Evolution & Development 17, 289–301. doi: 10.1111/ede.12138 Servais T, Perrier V, Danelian T, Klug C, Martin R, Munnecke A, Nowak H, Nützel A, Vandenbroucke TR, Williams M, and Rasmussen CM (2016). The onset of the ‘Ordovician Plankton Revolution’ in the late Cambrian. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 458, 12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.11.003 Van Roy P, Daley AC, and Briggs DEG (2015). Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. Nature 522, 77–80. doi: 10.1038/nature14256 Zeng H, Zhao F, Niu K, Zhu M, and Huang D (2020). An early Cambrian euarthropod with radiodont-like raptorial appendages. Nature 588, 101–105. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7 Zhao F, Caron JB, Bottjer DJ, Hu S, Yin Z, and Zhu M (2014). Diversity and species abundance patterns of the Early Cambrian (Series 2, Stage 3) Chengjiang Biota from China. Paleobiology 40, 50–69. doi: 10.1666/12056 | The origin and early evolution of arthropods | Cédric Aria | <p style="text-align: justify;">The rise of arthropods is a decisive event in the history of life. Likely the first animals to have established themselves on land and in the air, arthropods have pervaded nearly all ecosystems and have become pilla... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evo-Devo, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Invertebrate paleontology, Macroevolution, Paleobiodiversity, Paleobiology, Paleoecology, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Taphonomy, Taxonomy | Tae-Yoon Park | 2021-04-26 13:51:21 | View | |

26 Oct 2023

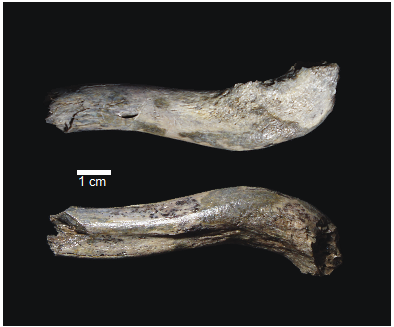

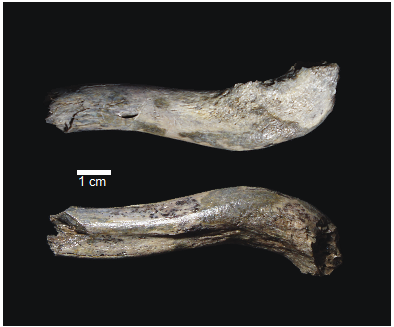

OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai GorgeCatherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656A new method for measuring clavicular curvatureRecommended by Nuria Garcia based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe evolution of the hominid clavicle has not been studied in depth by paleoanthropologists given its high morphological variability and the scarcity of complete diagnosable specimens. A nearly complete Nacholapithecus clavicle from Kenya (Senut et al. 2004) together with a fragment from Ardipithecus from the Afar region of Ethiopia (Lovejoy et al. 2009) complete our knowledge of the Miocene record. The Australopithecus collection of clavicles from Eastern and South African Plio-Pleistocene sites is slightly more abundant but mostly represented by fragmentary specimens. The number of fossil clavicles increases for the genus Homo from more recent sites and thus our potential knowledge about the shoulder evolution. In their new contribution, Taylor et al. (2023) present a detailed analysis of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominin clavicle recovered from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). The work goes over previous studies which included clavicles found in the hominid fossil record. The text is accompanied by useful tables of data and a series of excellent photographs. It is a great opportunity to learn its role in the evolution of the hominid shoulder gird as clavicles are relatively poorly preserved in the fossil record compared to other long bones. The study compares the specimen OH 89 with five other hominid clavicles and a sample of 25 modern clavicles, 30 Gorilla, 31 Pan and 7 Papio. The authors propose a new methodology for measuring clavicular curvature using measurements of sternal and acromial curvature, from which an overall curvature measurement is calculated. The study of OH 89 provides good evidence about the hominid who lived 1.8 million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge region. This time period is especially relevant because it can help to understand the morphological changes that occurred between Australopithecus and the appearance of Homo. The authors conclude that OH 89 is the largest of the hominid clavicles included in the analysis. Although they are not able to assign this partial element to species level, this clavicle from Olduvai is at the larger end of the variation observed in Homo sapiens and show similarities to modern humans, especially when analysing the estimated sinusoidal curvature. References Lovejoy, C. O., Suwa, G., Simpson, S. W., Matternes, J. H., and White, T. D. (2009). The Great Divides: Ardipithecus ramidus peveals the postcrania of our last common ancestors with African apes. Science, 326(5949), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1175833 Senut, B., Nakatsukasa, M., Kunimatsu, Y., Nakano, Y., Takano, T., Tsujikawa, H., Shimizu, D., Kagaya, M., and Ishida, H. (2004). Preliminary analysis of Nacholapithecus scapula and clavicle from Nachola, Kenya. Primates, 45(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-003-0073-5 Taylor, C., Masao, F., Njau, J. K., Songita, A. V., and Hlusko, L. J. (2023). OH 89: A newly described ∼1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge. bioRxiv, 526656, ver. 6 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.02.526656 | OH 89: A newly described ~1.8-million-year-old hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge | Catherine E. Taylor, Fidelis Masao, Jackson K. Njau, Agustino Venance Songita, Leslea J. Hlusko | <p>Objectives: Here, we describe the morphology and geologic context of OH 89, a ~1.8-million-year-old partial hominid clavicle from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. We compare the morphology and clavicular curvature of OH 89 to modern humans, extant apes... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Fossil record, Methods, Morphological evolution, Paleoanthropology, Vertebrate paleontology | Nuria Garcia | 2023-02-08 19:45:01 | View | |

14 Apr 2021

The impact of allometry on vomer shape and its implications for the taxonomy and cranial kinesis of crown-group birdsOlivia Plateau, Christian Foth https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.184101Vomers aren't so different in crown group birds when considering allometric effectsRecommended by Andrew Farke based on reviews by Sergio Martínez Nebreda and Roland SookiasToday’s birds are divided into two deeply divergent and historically well-documented groups: Palaeognathae and Neognathae. Palaeognaths include both the flight-capable tinamous as well as the flightless ratites (ostriches, rheas, kiwis, cassowaries, and kin). Neognaths include all other modern birds, ranging from sparrows to penguins to hummingbirds. The clade names refer to the anatomy of the palate, with the “old jaws” (palaeognaths) originally thought to more closely resemble an ancestral reptilian condition and the “new jaws” (neognaths) showing a uniquely modified bony configuration. This particularly manifests in the pterygoid-palatine complex (PPC) in the palate, formed from pairs of pterygoids and palatines alongside a single midline vomer. In palaeognaths, the vomer is comparatively large and the pterygoid and palatine are relatively tightly connected. The PPC is more mobile in neognaths, with a variably shaped vomer, which is sometimes even absent. Although both groups of birds show cranial kinesis, neognaths exhibit a much more pronounced degree of kinesis versus palaeognaths, due in part to the tighter nature of the palaeognath pterygoid/palatine interfaces. A previous paper (Hu et al. 2019) used 3D geometric morphometrics to compare the shape of the vomer across neognaths and palaeognaths. Among other findings, this work suggested that each clade had a distinct vomer morphology, with palaeognaths more similar to the ancestral condition (i.e., that of non-avian dinosaurs). This observation was extended to support inferences of limited vs. less limited cranial kinesis in various extinct species, based in part on observations of vomer shape. A new preprint by Plateau and Foth (2021) presents a reanalysis of Hu et al.’s data, specifically focusing on allometric effects. In short, the new analysis looks at how size correlates (or doesn't correlate) with vomer shape. Plateau and Foth (2021) found that when size effects are included, differences between palaeognaths and neognaths are less than the “raw” (uncorrected) shape data suggest. It is much harder to tell bird groups apart! Certainly, there are still some general differences, but some separations in morphospace close up when allometry—the interrelationship between shape and size—is considered. Plateau and Foth (2021) use this finding to suggest that 1) vomer shape alone is not a completely reliable proxy for inferring the phylogenetic affinities of a particular bird; and 2) the vomer is only one small component of the cranial kinetic system, and thus its shape is of limited utility for inferring cranial kinesis capabilities when considered independently from the rest of the relevant skull bones.

References Hu, H., Sansalone, G., Wroe, S., McDonald, P. G., O’Connor, J. K., Li, Z., Xu, X., & Zhou, Z. (2019). Evolution of the vomer and its implications for cranial kinesis in Paraves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19571–19578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907754116 | The impact of allometry on vomer shape and its implications for the taxonomy and cranial kinesis of crown-group birds | Olivia Plateau, Christian Foth | <p>Crown birds are subdivided into two main groups, Palaeognathae and Neognathae, that can be distinguished, among others, by the organization of the bones in their pterygoid-palatine complex (PPC). Shape variation to the vomer, which is the most ... |  | Comparative anatomy, Evolutionary biology, Macroevolution, Morphological evolution, Morphometrics, Taxonomy | Andrew Farke | 2020-07-03 14:16:48 | View | |

27 May 2020

The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK)Jérémy Anquetin, Charlotte André https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/7pa5cA recommendation of: The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK)Recommended by Hans-Dieter Sues based on reviews by Igor Danilov and Serjoscha EversStem- and crown-group turtles have a rich and varied fossil record dating back to the Triassic Period. By far the most common remains of these peculiar reptiles are their bony shells and fragments of shells. Furthermore, if historical specimens preserved skulls the preparation techniques at that time were inadequate for elucidating details of the cranial structure. Thus, it comes as no surprise that most of the early research on turtles focused on the structure of the shell with little attention paid to other parts of the skeleton. Starting in the 1960s, this changed as researchers realized that there is considerable variation in the structure of turtle shells even within species and that new methods of fossil preparation, especially chemical methods, could reveal a wealth of phylogenetically important features in the structure of the skulls of turtles. The principal worker was Eugene S. Gaffney of the American Museum of Natural History (New York) who in a series of exquisitely illustrated monographs revolutionized our understanding of turtle osteology and phylogeny. Over the last decade or so, a new generation of researchers has further refined the phylogenetic framework for turtles and continued the work by Gaffney. One of the specialists from this new generation is Jérémy Anquetin who, with a number of colleagues, has revised many of the Jurassic-age stem-turtles that existed in coastal marine settings in what is now Europe. Collections in France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK house numerous specimens of these forms, which attracted the interest of researchers as early as the first decades of the nineteenth century. Despite this long history, however, the diversity and interrelationships of these marine taxa remained poorly understood. In the present study, Anquetin and his colleague Charlotte André extend the fossil record of these stem-turtles, recently hypothesized as a clade Thalassochelydia, into the Early Cretaceous (Anquetin & André 2020). They present an excellent anatomical account on a well-preserved cranium from the Purbeck Formation of Dorset (England) that can be referred to Thalassochelydia and augments our knowledge of the cranial morphology of this clade. Anquetin & André (2020) make a good case that this specimen belongs to the same taxon as shell material long ago described as Hylaeochelys belli. References Anquetin, J., & André, C. (2020). The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK). PaleorXiv, 7pa5c, version 3, peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/7pa5c | The last surviving Thalassochelydia—A new turtle cranium from the Early Cretaceous of the Purbeck Group (Dorset, UK) | Jérémy Anquetin, Charlotte André | <p>**Background.** The mostly Berriasian (Early Cretaceous) Purbeck Group of southern England has produced a rich turtle fauna dominated by the freshwater paracryptodires *Pleurosternon bullockii* and *Dorsetochelys typocardium*. Each of these spe... |  | Comparative anatomy, Paleoecology, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Hans-Dieter Sues | 2020-01-30 10:37:07 | View | |

27 Jan 2020

A simple generative model of trilobite segmentation and growthMelanie J Hopkins https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/zt642Deep insights into trilobite developmentRecommended by Christian Klug based on reviews by Kenneth De Baets and Lukas LaiblTrilobites are arthropods that became extinct at the greatest marine mass extinction over 250 Ma ago. Because of their often bizarre forms, their great diversity and disparity of shapes, they have attracted the interest of researchers and laypersons alike. Due to their calcified exoskeleton, their remains are quite abundant in many marine strata. One particularly interesting aspect, however, is the fossilization of various molting stages. This allows the reconstruction of both juvenile strategies (lecitotrophic versus planktotrophic) and the entire life history of at least some well-documented taxa (e.g., Hughes 2003, 2007; Laibl 2017). For example, life history of trilobites is, based on certain morphological changes, classically subdivided in the three phases protaspis (hatchling, one dorsal shield with few segments with no articulation between), meraspis (juvenile, two and more shields connected by articulations) and holaspis (when the terminal number of thoracic segments is reached). At most molting events, a new skeletal element is added (only in the holaspis, the number of thoracic segments does not change). Nevertheless, many trilobites are known mainly from late meraspid and holaspid stages, because the dorsal shields of the first ontogenetic stages are usually very small and thus often either dissolved or overlooked. An improved understanding of trilobite ontogeny could thus help filling in these gaps in fossil preservation and subsequently, to better understand evolutionary pathways. This is where this paper comes in. In a very clever approach, the New-York-based researcher Melanie Hopkins modeled the growth of these segmented animals (Hopkins 2020). Previous growth models of invertebrates focused on, e.g., mollusks, whose shells grow by accretion. Modelling arthropod ontogeny represented a challenge, which is now overcome by Hopkins' brilliant paper. Her generative growth model is based on empirical data of Aulacopleura koninckii (Barrande, 1846). Hong et al. (2014) and Hughes et al. (2017) documented the ontogeny of this 429 Ma old trilobite species in great detail. In the Silurian of the Barrandian region (Czech Republic), this species is locally very common and all growth stages are well known. I could imagine that the paper of Hughes et al. (2017) planted the seed into Melanie Hopkins’ mind to approach trilobite development in general in a quantitative way with a mathematical approach comparable to the mollusk-research by, e.g., David Raup (1961, 1966) and George McGhee (2015). Hopkins’ growth model requires “a minimum of nine parameters […] to model basic trilobite growth and segmentation, and three additional parameters […] to allow a transition to a new growth gradient for the trunk region during ontogeny” (Hopkins 2020: p. 21). It is now possible to play with parameters such as protaspid size, segment dimensions, segment numbers, etc., in order to estimate changes in body size or morphology. Furthermore, the model could be applied to similarly organized arthropod exoskeletons like many early Cambrian arthropods (e.g., marellomorphs) or even crustaceans (e.g., conchostracans or copepods). Of great interest could also be to assess influences of environmental changes on arthropod ontogeny. Also, her work will help to reconstruct unknown developmental information missing from trilobite species (and possibly other arthropods) and also to explore their morphospace. References Barrande, J. (1846). Notice préliminaire sur le système Silurien et les trilobites de Bohême. Leipzig: Hirschfield.

Hong, P. S., Hughes, N. C., & Sheets, H. D. (2014). Size, shape, and systematics of the Silurian trilobite Aulacopleura koninckii. Journal of Paleontology, 88(6), 1120–1138. doi: 10.1666/13-142 | A simple generative model of trilobite segmentation and growth | Melanie J Hopkins | <p>Generative growth models have been the basis for numerous studies of morphological diversity and evolution. Most work has focused on modeling accretionary growth systems, with much less attention to discrete growth systems. Generative growth mo... |  | Evo-Devo, Evolutionary biology, Invertebrate paleontology, Paleobiology | Christian Klug | 2019-10-06 00:27:25 | View | |

16 Oct 2019

What do ossification sequences tell us about the origin of extant amphibians?Michel Laurin, Océane Lapauze, David Marjanović https://doi.org/10.1101/352609The origins of LissamphibiaRecommended by Robert Asher based on reviews by Jennifer Olori and 2 anonymous reviewersAmong living vertebrates, there is broad consensus that living tetrapods consist of amphibians and amniotes. Crown clade Lissamphibia contains frogs (Anura), salamanders (Urodela) and caecilians (Gymnophiona); Amniota contains Sauropsida (reptiles including birds) and Synapsida (mammals). Within Lissamphibia, most studies place frogs and salamanders in a clade together to the exclusion of caecilians (see Pyron & Wiens 2011). Among fossils, there are a number of amphibian and amphibian-like taxa generally placed in Temnospondyli and Lepospondyli. In contrast to the tree of living tetrapods, affinities of these fossils to some or all of the three extant lissamphibian groups have proven to be much harder to resolve. For example, temnospondyls might be stem tetrapods and lissamphibians a derived group of lepospondyls; alternatively, temnospondyls might be closer to the clade of frogs and salamanders, and lepospondyls to caecilians (compare Laurin et al. 2019: fig. 1d vs. 1f). Here, in order to assess which of these and other mutually exclusive topologies is optimal, Laurin et al. (2019) extract phylogenetic information from developmental sequences, in particular ossification. Several major differences in ossification are known to distinguish vertebrate clades. For example, due to their short intrauterine development and need to climb from the reproductive tract into the pouch, marsupial mammals famously accelerate ossification of their facial skeleton and forelimb; in contrast to placentals, newborn marsupials can climb, smell & suck before they have much in the way of lungs, kidneys, or hindlimbs (Smith 2001). Divergences among living and fossil amphibian groups are likely pre-Triassic (San Mauro 2010; Pyron 2011), much older than a Jurassic split between marsupials and placentals (Tarver et al. 2016), and the quality of the fossil record generally decreases with ever-older divergences. Nonetheless, there are a number of well-preserved examples of "amphibian"-grade tetrapods representing distinct ontogenetic stages (Schoch 2003, 2004; Schoch and Witzmann 2009; Olori 2013; Werneburg 2018; among others), all amenable to analysis of ossification sequences. Putting together a phylogenetic dataset based on ossification sequences is not trivial; sequences are not static features apparent on individual specimens. Rather, one needs multiple specimens representing discrete developmental stages for each taxon to be compared, meaning that sequences are usually available for only a few characters. Laurin et al. (2019) have nonetheless put together the most exhaustive matrix of tetrapod sequences so far, with taxon coverage ranging from 62 genera for appendicular characters to 107 for one of their cranial datasets, each sampling between 4-8 characters (Laurin et al. 2019: table 1). The small number of characters means that simply applying an optimality criterion (such as parsimony) is unlikely to resolve most nodes; treespace is too flat to be able to offer optimal peaks up which a search algorithm might climb. However, Laurin et al. (2019) were able to test each of the main competing hypotheses, defined a priori as a branching topology, given their ossification sequence dataset and a likelihood optimality criterion. Their most consistent result comes from their cranial ossification sequences and supports their "LH", or lepospondyl hypothesis (Laurin et al. 2019: fig. 1d). That is, relative to extinct, "amphibian"-grade taxa, Lissamphibia is monophyletic and nested within lepospondyls. Compared to mammals and birds (including dinosaurs), crown amphibian branches of the Tree of Life are exceptionally old. Each lissamphibian clade likely had diverged during Permian times (Marjanovic & Laurin 2008) and the crown group itself may even date to the Carboniferous (Pyron 2011). In contrast to mammoths and moas, no ancient DNA or collagen sequences are going to be available from >300 million-year-old fossils like the lepospondyl *Hyloplesion* (Olori 2013), although recently published methods for incorporating genomic signal from extant taxa (Beck & Baillie 2018; Asher et al. 2019) into studies of fossils could also be applied to these ancient divergences among amphibian-grade tetrapods. Ossification sequences represent another important, additional source of data with which to test the conclusion of Laurin et al. (2019) that monophyletic Lissamphibians shared a common ancestor with lepospondyls, among other hypotheses. **References** Asher, R. J., Smith, M. R., Rankin, A., & Emry, R. J. (2019). Congruence, fossils and the evolutionary tree of rodents and lagomorphs. Royal Society Open Science, 6(7), 190387. doi: [ 10.1098/rsos.190387 ](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rsos.190387 ) Beck, R. M. D., & Baillie, C. (2018). Improvements in the fossil record may largely resolve current conflicts between morphological and molecular estimates of mammal phylogeny. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1893), 20181632. doi: [ 10.1098/rspb.2018.1632](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rspb.2018.1632) Laurin, M., Lapauze, O., & Marjanović, D. (2019). What do ossification sequences tell us about the origin of extant amphibians? BioRxiv, 352609, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. doi: [ 10.1101/352609](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/352609) Marjanović, D., & Laurin, M. (2008). Assessing confidence intervals for stratigraphic ranges of higher taxa: the case of Lissamphibia. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 53(3), 413–432. doi: [ 10.4202/app.2008.0305](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.4202/app.2008.0305) Olori, J. C. (2013). Ontogenetic sequence reconstruction and sequence polymorphism in extinct taxa: an example using early tetrapods (Tetrapoda: Lepospondyli). Paleobiology, 39(3), 400–428. doi: [ 10.1666/12031](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1666/12031) Pyron, R. A. (2011). Divergence time estimation using fossils as terminal taxa and the origins of Lissamphibia. Systematic Biology, 60(4), 466–481. doi: [ 10.1093/sysbio/syr047](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/sysbio/syr047) Pyron, R. A., & Wiens, J. J. (2011). A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61(2), 543–583. doi: [ 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.012](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.012) San Mauro, D. (2010). A multilocus timescale for the origin of extant amphibians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 56(2), 554–561. doi: [ 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.019](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.019) Schoch, R. R. (2003). Early larval ontogeny of the Permo-Carboniferous temnospondyl *Sclerocephalus*. Palaeontology, 46(5), 1055–1072. doi: [ 10.1111/1475-4983.00333](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/1475-4983.00333) Schoch, R. R. (2004). Skeleton formation in the Branchiosauridae: a case study in comparing ontogenetic trajectories. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 24(2), 309–319. doi: [ 10.1671/1950](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1671/1950) Schoch, R. R., & Witzmann, F. (2009). Osteology and relationships of the temnospondyl genus *Sclerocephalus*. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 157(1), 135–168. doi: [ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00535.x](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00535.x) Smith, K. K. (2001). Heterochrony revisited: the evolution of developmental sequences. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 73(2), 169–186. doi: [ 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01355.x](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2001.tb01355.x) Tarver, J. E., dos Reis, M., Mirarab, S., Moran, R. J., Parker, S., O’Reilly, J. E., & Pisani, D. (2016). The interrelationships of placental mammals and the limits of phylogenetic inference. Genome Biology and Evolution, 8(2), 330–344. doi: [ 10.1093/gbe/evv261](https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/gbe/evv261) Werneburg, R. (2018). Earliest “nursery ground” of temnospondyl amphibians in the Permian. Semana, 32, 3–42. | What do ossification sequences tell us about the origin of extant amphibians? | Michel Laurin, Océane Lapauze, David Marjanović | <p>The origin of extant amphibians has been studied using several sources of data and methods, including phylogenetic analyses of morphological data, molecular dating, stratigraphic data, and integration of ossification sequence data, but a consen... |  | Evo-Devo, Phylogenetics, Systematics, Vertebrate paleontology | Robert Asher | 2018-06-22 08:21:31 | View | |

03 Jul 2024

Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successionsNiklas Hohmann, Joel R. Koelewijn, Peter Burgess, Emilia Jarochowska https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.18.572098Advances in understanding how stratigraphic structure impacts inferences of phenotypic evolutionRecommended by Melanie Hopkins based on reviews by Bjarte Hannisdal, Katharine Loughney, Gene Hunt and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bjarte Hannisdal, Katharine Loughney, Gene Hunt and 1 anonymous reviewer

A fundamental question in evolutionary biology and paleobiology is how quickly populations and/or species evolve and under what circumstances. Because the fossil record affords us the most direct view of how species lineages have changed in the past, considerable effort has gone into developing methodological approaches for assessing rates of evolution as well as what has been termed “mode of evolution” which generally describes pattern of evolution, for example whether the morphological change captured in fossil time series are best characterized as static, punctuated, or trending (e.g., Sheets and Mitchell, 2001; Hunt, 2006, 2008; Voje et al., 2018). The rock record from which these samples are taken, however, is incomplete, due to spatially and temporally heterogenous sediment deposition and erosion. The resulting structure of the stratigraphic record may confound the direct application of evolutionary models to fossil time series, most of which come from single localities. This pressing issue is tackled in a new study entitled “Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions” (Hohmann et al., 2024). The “carbonate successions” part of the title is important. Previous similar work (Hannisdal, 2006) used models for siliciclastic depositional systems to simulate the rock record. Here, the authors simulate sediment deposition across a carbonate platform, a system that has been treated as fundamentally different from siliciclastic settings, from both the point of view of geology (see Wagoner et al., 1990; Schlager, 2005) and ecology (Hopkins et al., 2014). The authors do find that stratigraphic structure impacts the identification of mode of evolution but not necessarily in the way one might expect; specifically, it is less important how much time is represented compared to the size and distribution of gaps, regardless of where you are sampling along the platform. This result provides an important guiding principle for selecting fossil time series for future investigations. Another very useful result of this study is the impact of time series length, which in this case should be understood as the density of sampling over a particular time interval. Counterintuitively, the probability of selecting the data-generating model as the best model decreases with increased length. The authors propose several explanations for this, all of which should inspire further work. There are also many other variables that could be explored in the simulations of the carbonate models as well as the fossil time series. For example, the authors chose to minimize within-sample variation in order to avoid conflating variability with evolutionary trends. But greater variance also potentially impacts model selection results and underlies questions about how variation relates to evolvability and the potential for directional change. Lastly, readers of Hohmann et al. (2024) are encouraged to also peruse the reviews and author replies associated with the PCI Paleo peer review process. The discussion contained in these documents touch on several important topics, including model performance and model selection, the nature of nested model systems, and the potential of the forwarding modeling approach. References Hannisdal, B. (2006). Phenotypic evolution in the fossil record: Numerical experiments. The Journal of Geology, 114(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1086/499569 Hohmann, N., Koelewijn, J. R., Burgess, P., and Jarochowska, E. (2024). Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions. bioRxiv, 572098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed by PCI Paleo. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.18.572098 Hopkins, M. J., Simpson, C., and Kiessling, W. (2014). Differential niche dynamics among major marine invertebrate clades. Ecology Letters, 17(3), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12232 Hunt, G. (2006). Fitting and comparing models of phyletic evolution: Random walks and beyond. Paleobiology, 32(4), 578–601. https://doi.org/10.1666/05070.1 Hunt, G. (2008). Gradual or pulsed evolution: When should punctuational explanations be preferred? Paleobiology, 34(3), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1666/07073.1 Schlager, W. (Ed.). (2005). Carbonate Sedimentology and Sequence Stratigraphy. SEPM Concepts in Sedimentology and Paleontology No. 8. https://doi.org/10.2110/csp.05.08 Sheets, H. D., and Mitchell, C. E. (2001). Why the null matters: Statistical tests, random walks and evolution. Genetica, 112, 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013308409951 Voje, K. L., Starrfelt, J., and Liow, L. H. (2018). Model adequacy and microevolutionary explanations for stasis in the fossil record. The American Naturalist, 191(4), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/696265 Wagoner, J. C. V., Mitchum, R. M., Campion, K. M., and Rahmanian, V. D. (1990). Siliciclastic Sequence Stratigraphy in Well Logs, Cores, and Outcrops: Concepts for High-Resolution Correlation of Time and Facies. AAPG Methods in Exploration Series No. 7. https://doi.org/10.1306/Mth7510 | Identification of the mode of evolution in incomplete carbonate successions | Niklas Hohmann, Joel R. Koelewijn, Peter Burgess, Emilia Jarochowska | <p><strong>Background:</strong> The fossil record provides the unique opportunity to observe evolution over millions of years, but is known to be incomplete. While incompleteness varies spatially and is hard to estimate for empirical sections, com... | Evolutionary biology, Evolutionary patterns and dynamics, Fossil record, Methods, Sedimentology | Melanie Hopkins | 2023-12-19 08:10:00 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jérémy Anquetin

Faysal Bibi

Guillaume Billet

Andrew A. Farke

Franck Guy

Leslea J. Hlusko

Melanie Hopkins

Cynthia V. Looy

Jesús Marugán-Lobón

Ilaria Mazzini

P. David Polly

Caroline A.E. Strömberg